Australian History

Australians: A historical library edited by Alan Gilbert and K.S. Inglis

As an ‘imagined community’, Australia ‘imagined imagining needs more that community’, most strenuous imagining than most. Post-colonial? Not really – we are recolonized over and over. Wall Street shivers, the Australian dollar gets pneumonia; Japan revises its shopping-list, and our coal industry verges on collapse. Britain’s hold began to loosen after World War II, but our cultural colonization by the United States was probably effective at least sixty-five years ago, by the time Australian cinema outlets had been secured for Hollywood, and closed off for local producers, through the nefarious block-booking system. With film and television, there never was much political will to defend ourselves; nor was there any, a year ago, to prevent the powerful American magnate Rupert Murdoch from taking over two-thirds of the press in what used to be his own country. There are moments and areas where it still seems reasonable to promote cultural nationalism, l not positive xenophobia.

... (read more)The Creative Spirit in Australia: A Cultural History by Geoffrey Serle

The perennial and increasingly tiresome question of Australian ‘national identity’ will probably diminish rapidly after the point where the design of a new and truly Australian flag is determined.

That it is a question at all, after just on two hundred years of settlement here, is curious. Part of the condition was diagnosed by the late Arthur Phillips in his studies of our colonial culture, The Australian Tradition, where he perceived in this country what he termed ‘the cultural cringe’. Phillips’ book, together with Vance Palmer’s The Legend of the Nineties and Russel Ward’s The Australian Legend, were emancipating surely.

... (read more)Reading My Place by Sally Morgan reminds one of how powerful a book can be when there is an urgent story to be told. This book, let me say at the outset, is wonderful.

Sally Morgan and her four brothers and sisters grew up in Perth in the 1950s and 1960s. They are part Aboriginal, but didn’t know it then. They knew they were darker, different, perhaps they were Greek; their mother and grandmother told them they were Indian and this answer satisfied the kids at school, and them for a time.

... (read more)Much that is published on the Centre is from the perspective of the jet-and-chopper journalist, so it is with sheer delight that one greets Man from Arltunga, written from the perspective of a local and a bushman. The author’s knowledge of this country is of a rare quality. Not only is he interested in the White settlement of the area but he also has a broader appreciation for the prehistory and for the Black version of their history. In the thirteen years that Dick Kimber has lived in the Centre he has travelled extensively with Aboriginal people through their ancestral country. He has travelled the Aboriginal way, with Aboriginal navigators, journeying slowly, digressing for relatives, or for bush tucker, or for ceremonial business. His first-hand knowledge together with his affinity for the country made him an ideal companion for Walter Smith on their journey to record Walter’s story.

... (read more)The Oxford History of Australia, Volume 4: The Succeeding Age by Stuart Macintyre

The appearance of a volume in the Oxford History of Australia would be an important event in its own right, but coming on the eve of the Bicentennial flood of historical publications it assumes special significance. The publishers and the general editor of the series had hoped to launch all five volumes in the series well before the market is awash with books, but this plan might now be shipwrecked on the rocks of misfortune.

... (read more)The Ministers’ Minders: Personal advisers in national government by James Walter

The official myth of the relationship between the elected political leaders and the bureaucrats charged with the administration of their decisions has been that it is for the politicians to set the ends, choose the values, and for the bureaucrats to advise on the means for the implementation of those values. The bureaucratic advice is to be objective and impartial as bureaucrats are there to serve governments committed to very different political values. But the myth has not always fitted the reality; facts and values are not so easily distinguished. James Walter in The Ministers’ Minders: Personal advisers in national government documents the emergence of a new political role in Western parliamentary democracies from this inevitable gap between the administrative and executive arms of government; and he explores the implication of this both for traditional ways of understanding political decision-making, and the range of role options open to political activists.

... (read more)The Australian Year: The chronicle of our seasons and celebrations by Les A. Murray

The Australian Year looks like the dreaded coffee table book, yet another gloss on the national ‘identity’, backed by Esso, and fit for export only. Certainly, the cover picture of parroty water gives that impression, as do many familiar ones inside, though the main photographer, Peter Solness, does turn in some good homely details as well. Generally, the photographs stand like an avenue of plane trees, their density and hues changing with the seasons of Les Murray’s fully ripened, free-ranging text – which meets the high expectations we might be forgiven for holding when a major Australian poet, a well-versed country boy and populist by persuasion, an erudite and vernacular singer of the old and new, writes a book on a phenomenon as democratically inclusive and resonant as the seasons.

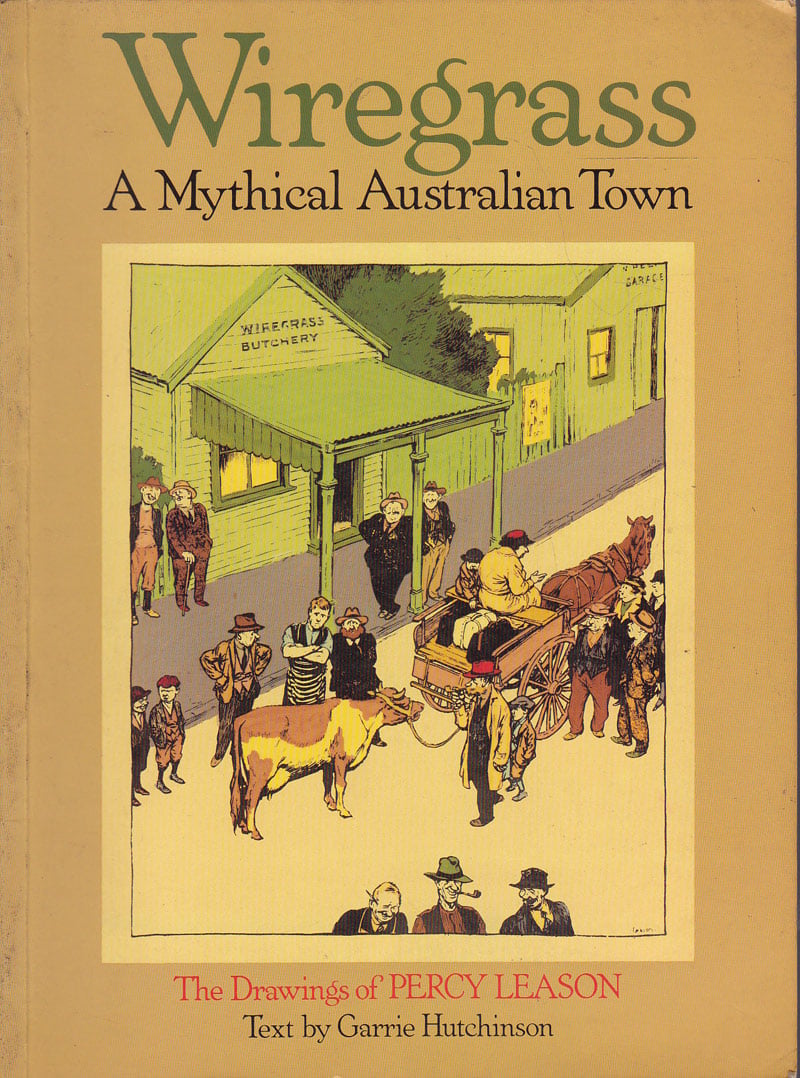

... (read more)From the beginnings of white settlement, Australia has had, an economy based almost entirely on rural production. The effects of a rural economy and population influencing broad social attitudes, not surprisingly, has resulted in a culture wherein the ‘up-country bushman’ and the legendary ‘outback’ are the very essence of this nation’s lore. And comedy has been a significant element of the lore. The early Australian writers ‘Steele Rudd’, Edward Dyson, ‘Banjo’ Patterson and Henry Lawson among many have celebrated some aspect of country life, as it was, with comedy; and so, of course, have the black and white artists working for the Australian press. Indeed, Australia today is the last remaining country observing her rural origins in graphic satire. One of the more significant twentieth century creators of Australian bush comedy was the magnificent pen-draughtsman Percy Leason.

... (read more)Australian War Strategy 1939-1945 by John Robertson and John McCarthy

Publishing collections of documents takes several forms and meets different needs. There are the great series of volumes that strive to leave nothing significant out, such as Mansergh’s Transfer of Power on Indian independence; there are the individual illustrative examples commonly published in the midst of a work of secondary prose; and there are the single volume or so works that strive to be more selective, so as to render the taste of the greater feast in more manageable proportions. These different approaches satisfy the intellectual appetite rather as a banquet, an after dinner mint and a cottage-pie respectively answer humankind’s more common hunger.

... (read more)They Meant Business edited by Bruce Hinchliffe & Sworn To No Master by Rod Kirkpatrick

Among the many attributes of the editor of ABR is his capacity for whimsy. (The current acting editor would like to think she shares this trait and has therefore left this bit in, believing, with Muriel Spark, that ‘the more truths and confusions the better.’) He knows full well of my own political, industrial, and academic struggles in the chill of sunny Queensland; I am, in a sense, the last person who should have been asked to review these books.

Having been set the task, however, I’ll try to look at the situation through the wrong end of a metaphorical telescope, and, thus distancing myself, I evaluate as follows.

... (read more)