Australian History

In a recent history of punishment in Australia, Mark Finnane observes that there is a ‘seemingly inexhaustible vein of convict history’. This has been especially true most recently of the history of convict women and the increasing number of accounts which are now being published in this field is to be welcomed. These studies offer a corrective to histories which have relegated convict women to a footnote, and, perhaps more significantly, some historians have attempted to reconceptualise and recast our understandings of colonialism, gender, power, and sexuality during the nineteenth century.

... (read more)A Life on the Ocean Wave: Voyages to Australia, India and the Pacific from the journals of Captain George Bayly 1824–1844 edited by Pamela Statham and Rica Erickson

A white-haired, white-bearded Captain George Bayly peers benignly out at us from the 1885 photograph frontispiece of A Life on the Ocean Wave. With epaulettes to his black uniform jacket, braided sleeves, a sword at his side and a ceremonial captain’s head-piece on the table beside him, Bayly looks the quintessential retired man of the sea. He looks like a man Charles Dickens should have been describing. We should be meeting him in some sea-side parlour, in some sailortown tea-palace. He looks as if he has a story to tell.

... (read more)I remember a conversation a year or so ago with an Australian scholar who had recently returned after a stint in Europe and was astonished to hear colleagues refer to Henry Reynolds as a ‘populariser’ and not true historian. I’ve heard it myself. Now that Reynolds has become a full-time writer we can expect to hear it more often. All of which goes a long way toward explaining why academic history is in decline.

... (read more)Jane Austen’s aunt was once at risk of transportation to Botany Bay for shoplifting. It is piquant that Austen named two of her major male characters Fitzwilliam Darcy in Pride and Prejudice and Captain Wentworth in Sense and Sensibility, because a leading inhabitant of New South Wales in those years was D’Arey Wentworth, disreputable but acknowledged kinsman of Lord Fitzwilliam. D’Arey Wentworth’s career smacks more of Georgette Heyer than Jane Austen, since he was a highwayman four times acquitted. Rather than push his luck further, he went, a free man, as assistant surgeon with the Second Fleet in 1790. As a young teenager Jane Austen may have read about him in the Times.

... (read more)

The Reds: The Communist Party of Australia from origins to illegality by Stuart Macintyre

The fascinating remembrance of the first two decades of the Communist Party of Australia is the first general history of Australian communism since Alastair Davidson’s The Communist Party of Australia: A short history appeared in 1969. Stuart Macintyre’s The Reds is both erudite and, as befits a former CPA member of Presbyterian background, is infused with moral vision.

... (read more)The title is not provocative: The Brisbane Line Controversy, but Paul Burns’s subtitle flags the partisanship that will mark his study. This is a case, he contends, of ‘Political Partisanship versus National Security 1942–45’. His conclusion is unobjectionable: ‘belief in a “Brisbane Line” was our barometer of fear about the vulnerability of our own continent which no Australian Army could negate’. In political demonology, the Brisbane Line signifies the intention of the Menzies–Fadden conservative governments of 1939–41 to abandon all but the south-east corner of Australia to the Japanese, should an invasion come. Burns is keen to absolve Menzies and his colleagues of blame and to find where, and with whom, the notion of the Line originated. In the process he indicts Labor front-bencher Eddie Ward, whose allegations about a Brisbane Line led to a Royal Commission in the election year of 1943.

... (read more)Since its initial publication in 1906, Who’s Who in Australia has dominated the market for contemporary biographical information in Australia. Founded by Fred Johns, an Adelaide journalist and Hansard reporter, it began as Johns’s Notable Australians, changed to Fred Johns’s Annual, became the Who’s Who in the Commonwealth of Australia for the sixth edition in 1922 and settled on its current name in 1927. After Johns died in 1932, the publication was taken over by the Herald and Weekly Times, and Who’s Who was issued every three years from 1935 to 1991.

... (read more)Paradise Mislaid: In search of the Australian tribe of Paraguay by Anne Whitehead

It was perhaps a fair return because in 1893, when the first 200 Australian settlers took up the land given to them by the Paraguayan Government to establish their Utopian paradise, they found one thousand Guarani Indians living on the land. They were ‘expelled’.

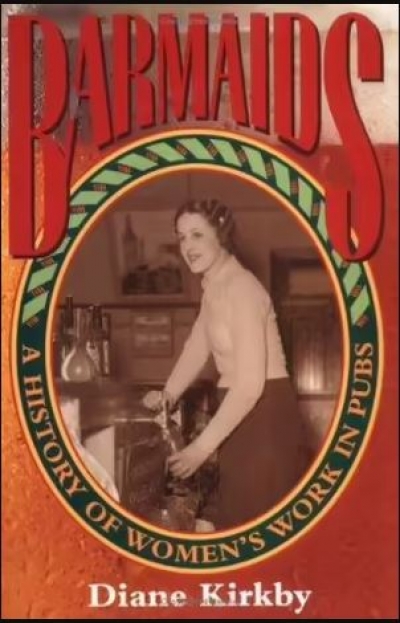

... (read more)Barmaids: A history of women’s work in pubs by Diane Kirkby

No icon better encapsulates the ethos of male culture than the pub. Sharing a beer in this bastion of male conviviality has been a defining experience in shaping Australian male identity. The pub as a cultural and social institution has attracted the attention of many historians, but none have considered the ubiquitous and yet mysteriously anonymous figure of the barmaid. Although represented in fiction and film, and up until recently, a part of the very fabric of pub culture, the barmaid remains an elusive figure in Australian history.

... (read more)Speaking Out of Turn: Lectures and speeches, 1940–1991 by Manning Clark

I heard Manning Clark lecture just once. It was in 1981. He was addressing a hall packed with school students who were attending a history camp at the Australian National University. That night, Clark demonstrated two qualities which distinguish most good lecturers: he played a character who was an enlarged version of himself, and he convinced the gathering that his topic was central to any understanding of the human condition. He told his young audience that they were faced with a great choice. With their help, Australia might one day become millennial Eden – a land where men and women were blessed with riches of the body and of the spirit. But if they were neglectful, he warned, their country would remain oppressed by a great dullness: Australia would continue to languish as a Kingdom of Nothingness. (This speech, it should be noted, was delivered in the middle of that bitter decade which followed the dismissal.)

... (read more)