Fiction

Garry Disher’s World War II novel Past the Headlands (2001) was inspired in part by his discovery of the diary of an army surgeon in Sumatra, who wrote of how his best friend was trying to arrange passage on a ship or plane that could take them back to Australia before the advancing Japanese army arrived. But one morning the surgeon woke to find that his friend had departed during the night. Mateship in a time of adversity, that most vaunted of masculine Australian virtues, had turned out to be a sham. The elusiveness of real friendship and love, and the difficulty of discerning what is true and what is false in human conduct, are recurring themes in Disher’s writing, and he visits them again in his latest book, Bitter Wash Road.

... (read more)Imagine a cross between Tim Winton’s The Turning and Kenneth Cook’s Wake in Fright, and you might very well imagine John Kinsella’s latest collection of fiction, Tide. Kinsella, a Western Australian like Winton, writes of the coast and of the desert, of small-town life and small-town people. However, Kinsella highlights the corruption of those landscapes and people in a way that aligns his vision more with Cook’s (which should come as no surprise, given Kinsella’s anti-pastoral poetry). There are ships pumping ‘alkaline hell’ into the waters where children swim, meatworks leaking blood to the sharks, factories, mines, old batteries, and trenches. Men are ‘brutal and brutalising’. Even boys torment and humiliate one another, often with the approval or complicity of their guardians. If someone outside Australia wanted to understand a country that hounded its first female prime minister out of office and voted in Tony Abbott on a platform against boat people and the carbon tax, this is the book I would recommend.

... (read more)

Fiona Wood’s second novel addresses a theme that is common in Young Adult fiction: the loss of innocence. Wildlife, a cleverly composed coming-of-age novel, introduces the reader to the world of Crowthorne Grammar’s outdoor education campus at Mount Fairweather. Although it revisits the character of Lou from Wood’s début novel, Six Impossible Things (2010), Wildlife is an absorbing, stand-alone book.

... (read more)With a stepmother she hates and a father who’s barely there, sixteen-year-old Danby Armstrong knew Christmas Day would be bad, but she wasn’t expecting the apocalypse. While families tear the wrapping off the latest iGadgets and share excited status updates, something strange happens. Suddenly, people are not just reading each other’s thoughts in their news feeds; they’re actually in each other’s heads. Everything from a neighbour’s affair to a planned terrorist attack is suddenly known; ‘the elephants in every room had been set loose to stampede’. Sydney erupts in violence as people seek revenge or just a place to shut out all those voices. But while Danby can hear them, they can’t hear her, and that makes her almost invisible.

... (read more)What a scandal! The Blessed Virgin sprawled on a bed in the half-dark, dead as a doornail, belly swollen, bare legs sticking out for all the world to see. What could Caravaggio have been thinking of?

... (read more)The depredations of time on the ageing human is an unusual topic for a young writer to confront, especially in a first novel, but why not, if the negative capability is not wanting? After all, it’s common enough for an older writer to inhabit young characters. The difference is, of course, that a young writer hasn’t yet been old. In Fiona McFarlane’s first novel, The Night Guest, the main centre of consciousness, through whom the whole narrative is perceived, is more than twice the author’s age. In an interview in the Sydney Morning Herald, McFarlane revealed that both her grandmothers suffered from dementia and that writing about Ruth, a seventy-five-year-old widow who is clearly becoming increasingly confused (the D-word is never used), is an act of homage and remembrance.

... (read more)Books of the Year is always one our most popular features of the year. Find out what 30 senior contributors liked most this year – and why.

... (read more)Authentically owning a character’s experience is one of the great challenges faced by fiction writers, especially when it is something as intensely felt as living with terminal illness. It is testimony to A.J. Betts’s talent that she does so in Zac & Mia without lapsing into melodrama, rather, maintaining a voice that is youthful, contemporary, ...

In the German kingdom of Hessen-Cassel, twelve-year-old Dortchen Wild falls in love with her scholarly neighbour Wilhelm Grimm amid the turbulent lead-up to the Napoleonic Wars. When Wilhelm and his brother Jakob undertake the task of collecting folk and fairy tales to preserve their national heritage, Dortchen becomes a willing source and participant, telling Wilhelm many of the stories that will become the Grimm brothers’ most famous ones. The romance between Dortchen and Wilhelm unfolds gently as Dortchen matures into womanhood. But no fairy tale is complete without a wicked stepmother or an impenetrable briar wood, and so it is with The Wild Girl. Her bright hopes are thwarted both by Wilhelm’s desperate poverty, and by the malevolent shadow of her own father, which soon coalesces into a reality of violence and abuse.

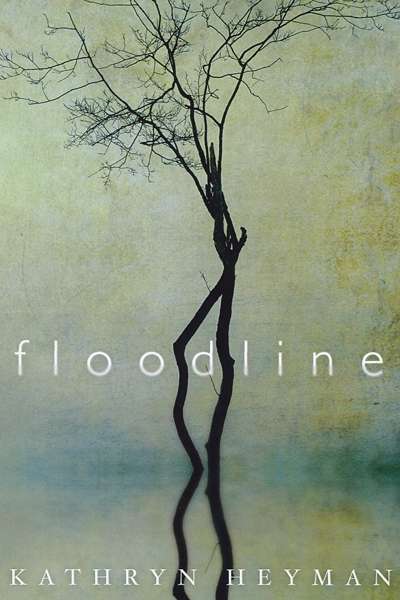

... (read more)Floodline is the fifth novel by Kathryn Heyman, course director at Allen & Unwin’s Faber Academy. Set in an unspecified area of the United States, it follows a proselytising family, which is on a mission to save the godless inhabitants of Horneville on the eve of their annual gay mardi gras, Hornefest, when the city is devastated by floods.

... (read more)