Fiction

I interviewed Lindsay Tanner once, back in 2012. Tanner was sixteen months retired from political life, and I had come seeking insight into the workings of the Victorian ...

... (read more)It is the morning after a husband's affair has been discovered, and the house is in chaos: the opening to Tolstoy's Anna Karenina (1877) is deliberately evoked in Toni ...

... (read more)Two doors, two characters, two colours – black and white – produce a surfeit of grey in John Hughes's short allegorical novel Asylum. Featuring a variety of forms ...

... (read more)Australian-born Dominic Smith grew up in Sydney but has spent most of his adult life in the United States; he currently lives in Austin, Texas, where he is claimed ...

... (read more)Among Don DeLillo's sixteen previous novels, White Noise (1985) is commonly held up as the apotheosis of his satirical vision, while his postwar epic Underworld ...

... (read more)'That was the summer ...' begins Josephine Rowe's début novel, A Loving, Faithful Animal, and with this classic overture she evokes that most common of literary tropes, the summer in adolescence that changes everything. But this is the summer, she continues, when a sperm whale washes up dead at Mount Martha, and all the best cartoons go off the air, replac ...

While reading Julian Barnes's latest novel, I recalled the day forty years ago when Philippe Petit spent an hour on a cable slung between the tops of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre. The image of that minuscule figure dancing back and forth between those massive buildings was a perfect metaphor for the life of Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–7 ...

Jack Kerouac spent his elderly years sequestered in a crumbling Mexican hacienda that 'smelt like beer and farts'; his amphetamines replaced with antacids, his octogenarian skin 'the colour and texture of beef jerky'. Never mind that Kerouac actually drank himself to an early death in Florida, because somehow this alternate universe, the starting point of Lynnette L ...

In early 1960s Paris, an eighteen-year-old who is keeping up his student enrolment to delay compulsory military service is questioned by the police because his name has been found in an address book. At the same time, a slightly older young woman is also being interrogated. The boy contrives to meet her afterwards in a café. Thus begins a story which is part romanc ...

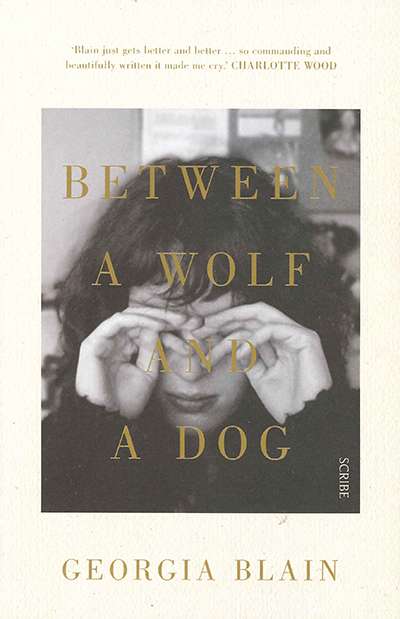

Between a Wolf and a Dog is Georgia Blain's eighth book: it follows five previous novels, an acclaimed short-story collection (The Secret Lives of Men, 2013) and Births, Deaths, Marriages (2008), a sublime memoir-in-essays. Blain has an affinity for domestic realism with a dark edge and an unstinting eye: she is fascinated by the faultline ...