Film

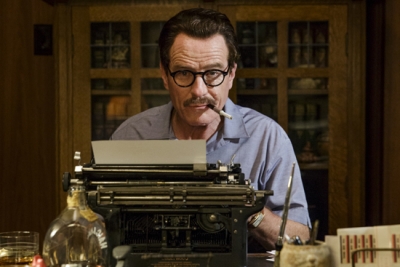

In 1950 a number of Hollywood screenwriters, including Dalton Trumbo, were sentenced to almost a year's imprisonment for contempt of Congress. Their 'crime' was a failure to answer questions from the House Un-American Activities Committee about their involvement with the Communist ...

... (read more)Film publicity is rarely subtle, so don't see Brooklyn if you are looking for the love-triangle tearjerker that its release poster promises. A film with its source in the spare, luminous writing of Colm Tóibín – as perceptive about women as any man writing – is never going to be standard Hollywood ...

... (read more)Often I am not proud of my profession, but there are times – usually when looking beneath the stones that shore up the established order – when journalists change the world for the better. The uncovering of the extent of sexual abuse of children, particularly by Catholic priests, is ...

... (read more)As with many fine Australian films, Looking For Grace opens with arid, spectacular landscape. Aerial shots of remote two-lane highways highlight expanses of blonde dirt, granite, and shrubbery across the Western Australian wheat belt, where the film was shot on location. These colours are ...

... (read more)It is a Hollywood staple: C meets T; they fall in love; obstacles stand in their way (a husband, a boyfriend, but most particularly the attitudes of the 1950s); obstacles are mostly overcome, and C and T march happily into the future together. In Todd Haynes's film, Cate Blanchett plays Carol, a ...

... (read more)'Meditative' is not perhaps the epithet that comes to mind in relation to most films, but it is entirely apt when applied to Paolo Sorrentini's new film, Youth, which will no doubt be fallen upon avidly by the many admirers of his previous film, The Great Beauty (2013). Several minutes before the opening title ...

It has been intriguing to watch the culture war surrounding the James Bond franchise. Slowly mobilising for a while now, the lead-up to the latest instalment, Spectre, the twenty-fourth Bond film, and the second directed by Sam Mendes, has seen it kick up a notch. Is the character a misogynist? Is he too violent? Maybe the next Bond should be black – a de ...

I'm back, you bastards.' Jocelyn Moorhouse announces her return to the screen after eighteen years as vehemently as does her lead character, Tilly Dunnage, when she arrives in the one-horse outback town of Dungatar. The bus moves through a brown sea of wheat beautifully and cinematically, and when Tilly (Kate Winslet) steps down from the bus, she may carry a sewing ...

'All happy families are alike, but an unhappy family is unhappy after its own fashion.' The famous opening line of Anna Karenina is thematically relevant to arts and culture the world over. Audiences are endlessly fascinated by the vicissitudes of the family unit. As an inherently domestic medium, television has a particularly lively relationship with ...

It has been said we get the versions of Shakespeare that mirror our times. If so, it is chilling to speculate what Australian director Justin Kurzel’s take on Macbeth, the story of a loyal warrior who succumbs to the temptation to commit regicide, says about the current state of the world.

Macbeth, Shakespeare’s darkest and bloodiest tale, ...