Recent reviews

Film | Theatre | Art | Opera | Music | Television | Festivals

Welcome to ABR Arts, home to some of Australia's best arts journalism. We review film, theatre, opera, music, television, art exhibitions – and more. To read ABR Arts articles in full, subscribe to ABR or take out an ABR Arts subscription. Both packages give full access to our arts reviews the moment they are published online and to our extensive arts archive.

Meanwhile, the ABR Arts e-newsletter, published every second Tuesday, will keep you up-to-date as to our recent arts reviews.

Recent reviews

Devotees of Wes Anderson know what to expect, and they certainly get it in spades in The French Dispatch. Those who sensed that the American director lost his way with The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), may feel he has strayed even further from the simplicity of the works that made him famous, such as the understated Bottle Rocket (1996), the quirky and endearing Rushmore (1998), and that masterpiece of whimsy, The Royal Tenenbaums (2001). The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson’s homage to Stefan Zweig set in a European alpine resort, has much in common with his latest film; an episodic, phantasmagorical, excessive, and, at times, indulgent work. It met with mixed reviews and was described as ‘kitschy’ and ‘curiously weightless’, epithets which might apply equally to his The French Dispatch, largely for its overlong zany scenes which appear arbitrary in relation to the action.

... (read more)Jean-Philippe Rameau’s setting of Adrien-Joseph Le Valois d’Orville’s adaptation of Jacques Autreau’s then unpublished and unperformed play Platée must be considered one of the most tactless entertainments ever presented to celebrate a royal wedding. The story of the ugly, vain water nymph who is used as a pawn to salvage the rocky marriage of Jupiter and Juno was certainly not the usual bland extravaganza to be expected at such an occasion. It probably didn’t help that the Dauphin Louis’s bride, Maria-Theresa of Spain, was not considered conventionally attractive.

... (read more)The Moulin Rouge journey has been a complicated one. The show, based on Baz Luhrmann’s 2001 movie and produced by Gerry Ryan’s Global Creatures, opened on Broadway in 2019, when it won a swag of Tony Awards, including Best Musical. In July of that year, a date for the Melbourne première was announced. A year later, of course, the world was turned upside down. Reports of the cast caroming between Melbourne and Sydney, trying unsuccessfully to avoid snap lockdowns, suggest something of the chaos behind the scenes these last six months. Now, belatedly, the velvet curtain has gone up and audiences are tentatively flocking – the only way one can flock these days – to this irradiated red mist of a musical.

... (read more)Cinema and poetry make for a less obvious coupling than cinema and theatre or cinema and painting, but once you start counting, the number of movies about poets and their world is surprisingly high. Granted, there’s more about scandal than scansion in most of them, but the list, just from those I remember seeing, is impressive: The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934), The Bad Lord Byron (1949), Stevie (1978), Gothic (1986), Barfly (1987), D’Annunzio (1987), Tom & Viv (1994), Total Eclipse (1995), Sylvia (2003), and Bright Star (2009). Within only the past five years we’ve been treated to Neruda, Dominion or the alternatively named Last Call (about the final hours of Dylan Thomas), Mary Shelley (which, like Gothic, ropes in Byron as well as the title character’s poet–spouse, with Coleridge added to the mix), and two bardic biopics from director Terence Davies: A Quiet Passion (2016) and the newly released Benediction. Might Davies, you wonder, be planning a third such venture, to match his acclaimed semi-autobiographical trilogy about working-class life in Liverpool from the 1940s to the 1960s?

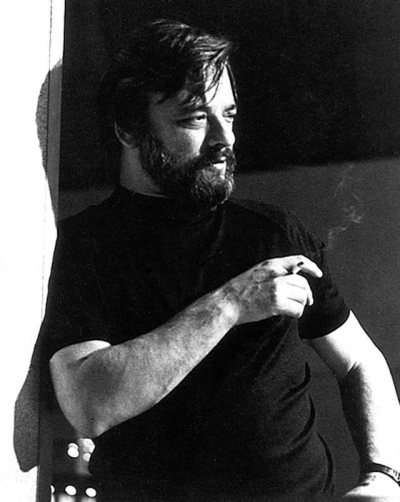

... (read more)I’ve often wondered what it would be like to witness the extinguishing of a genius who not only defined an era or a movement but also ruptured an art form. Virtually nothing of Shakespeare’s death is recorded, so we are left to invent the dying of that light. Mozart’s funeral was infamously desultory, and Tolstoy’s swamped by paparazzi as much as by the peasantry. Stephen Sondheim, the single greatest composer and lyricist the musical theatre has ever known, died at his home in Connecticut on 26 November, and we who loved him feel the loss like a thunderbolt from the gods. Not because we’re shocked – he was ninety-one after all – but simply because we shall not see his like again.

... (read more)Frederick McCubbin – Whisperings in wattle boughs

Frederick McCubbin (1855–1917), otherwise known as ‘The Proff’, was only a sometime plein-airiste at the Box Hill artists’ camp. He never made it out to Eaglemont and Heidelberg, as curator and historian Anna Gray has shown, debunking mythic accretions of place around the venerated so-called Heidelberg School. Boxhill/Lilydale, laid down in 1882, was McCubbin’s trainline of choice. He was also a studio artist given to creating a tightly controlled narrative mise en scène. As Andrew McKenzie has revealed, McCubbin built a faux grave in his backyard at his home in Rathmines Street, Hawthorn, dragooning his wife, Annie, to play the female mourner for Bush Burial (1990). The bearded elder was possibly John Dunne, a picaresque character whom McCubbin purportedly accosted on a city street. Artist friend Louis Abrahams played the young male mourner. The young girl is not identified. Nor the sorrowful dog.

... (read more)Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, first performed in 1599, is deeply interested in the difference between sleeping and wakefulness, if sleeping is equivalent to wilful ignorance and being awake means political consciousness. Characters throughout the play can’t sleep, won’t sleep, sleep on stage, are roused from sleep; they dream, and their eyes open and close, put to an eternal sleep. Before officially joining the conspiracy to murder Caesar in the Capitol, the play’s hero Brutus receives three letters from the conspirators Cassius and Casca entreating him to open his eyes to Caesar’s tyrannical aims: ‘Brutus, thou sleep’st; awake’. Once awake, it is his duty to ‘Speak, strike, redress’. The play’s language of sleep is strikingly similar to twenty-first century discourses of wakefulness – whether a woke sensitivity to issues of social justice, or the rioters at the United States Capitol shouting, ‘Wake up to the steal!’

... (read more)As is often the case with Shakespeare, theories and counter-theories about the provenance of As You Like It (probably 1599 or early 1600) have floated around for centuries. One such theory posits that the play is Love’s Labour’s Won, the ‘lost’ sequel – or more accurately second part of a literary diptych – to Love’s Labour’s Lost (1595–96) and that As You Like It is actually the play’s subtitle. This would align with Shakespeare’s finest comedy, Twelfth Night, which has the subtitle What You Will. Take that as you like it and make of it what you will.

... (read more)A Buddhist prayer wheel is a cylinder stuffed with sacred mantras and set on a spindle. Turning the cylinder is supposed to produce the same benefit as chanting the texts aloud. For true believers, contemplation of the endless turning of the wheel can be an aid to meditation and a way of drawing nearer to enlightenment. In nineteenth-century Europe, however, the wheel – dismissed by missionaries as a prayer machine – became a popular symbol for the withering effects of technology on the soul: an image of a hand-held mechanical device elevated to the medium of spiritual agency.

... (read more)As the author of Rock Chicks: The hottest female rockers from the 1960s to now (2011), I was excited to plunge back into the world of rock and roll to review the Linda McCartney retrospective that is currently showing at the Art Gallery of Ballarat. I’ve also written about Paul McCartney and John Lennon, so am quite familiar with these lads from Liverpool.

... (read more)