Gerhard Richter: The life of images (QAGOMA)

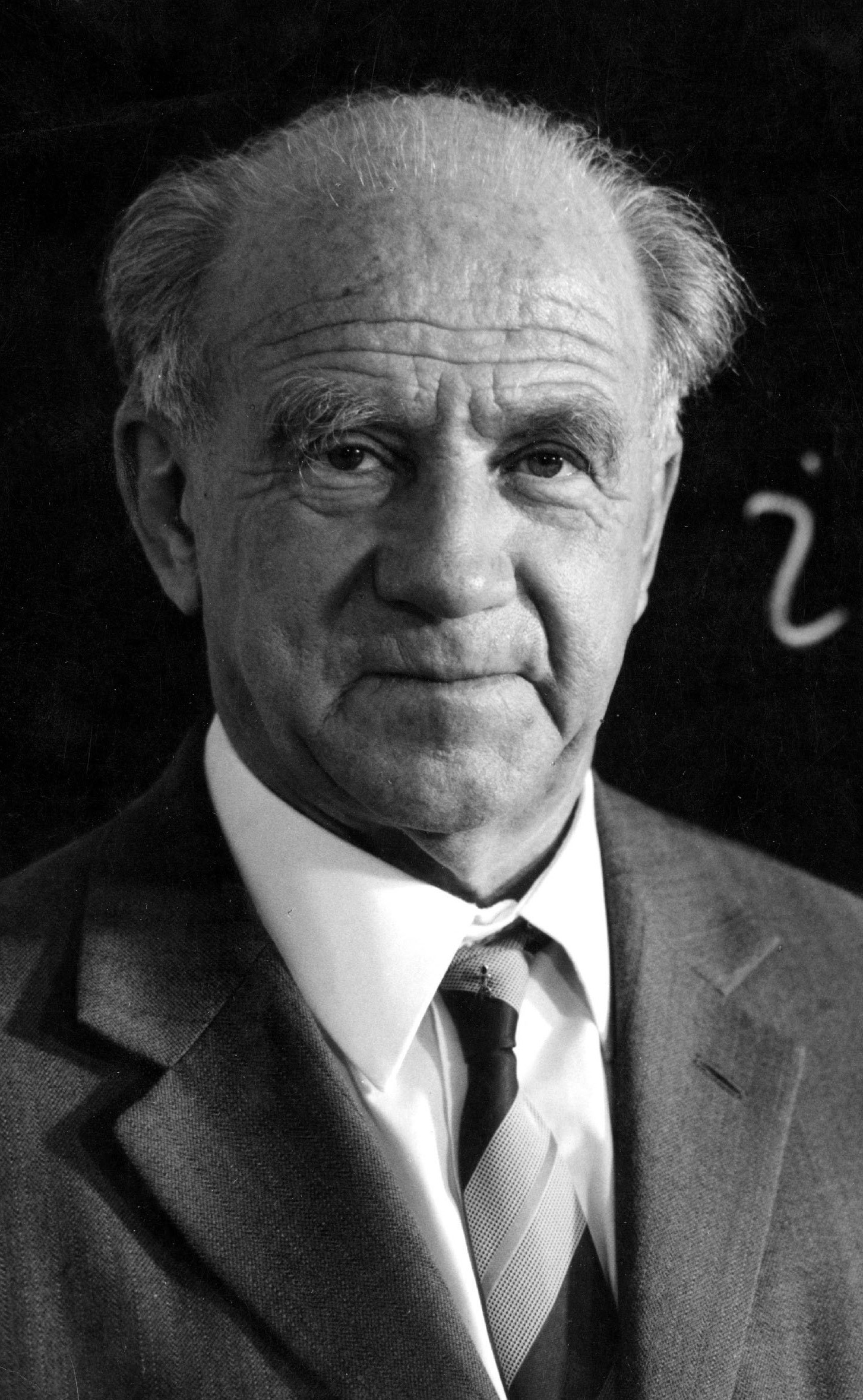

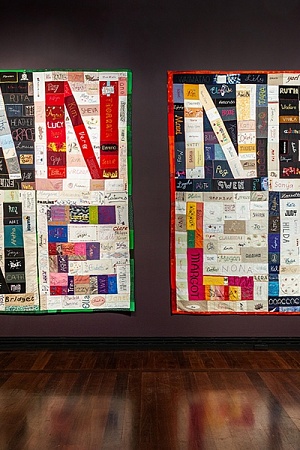

A rainy weekend heralded the opening of Gerhard Richter’s exhibition at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art. Gerhard Richter is famous for achieving the highest auction price for a living European artist (Abstraktes Bild fetched US$46.3 million in 2015), but his importance as an artist is due to his commitment to painting during a postwar period when many had abandoned the medium. The associated mental image may be a dominant ‘bass note’ of grey in tune with the Brisbane weather. Yet, as the exhibition makes clear, there is prescience in Richter’s work; his interest in probing at the casual photography that has become the ubiquitous feature of our times.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.