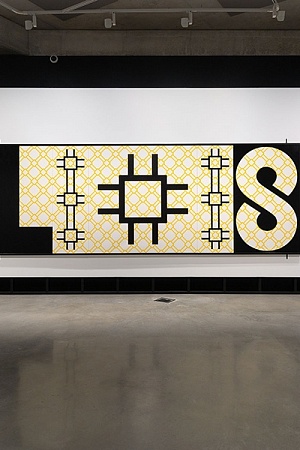

Nude: Art from the Tate collection (Art Gallery of New South Wales)

There is an underlying theme to Nude: Art from the Tate collection: the tussle between the desire to connect humanity to mythology by shrouding our naked forms in grand narratives, and the will to see human nudity both objectively and subjectively, but most importantly as entirely our own human experience. This struggle plays out as the exhibition weaves through nine rooms, tracing the role of the nude in art through recent centuries as a passage from archetypal classicism to raw vulnerability. Each room has been given either an art-historic or thematic title.

The viewer is welcomed by two figures from Greek mythology, the Greek God of the soul in Frederick Lord Leighton’s The bath of Psyche (1890) and the athletic figure of Greek archer Teucer (1881), immortalised in bronze by Hamo Thornycroft. Albeit superbly crafted, these archetypes of male and female beauty are somehow devoid of human warmth. Psyche’s pale skin, although painted in oils, has the cool perfection of marble. The smooth precision of her form is the more apparent by comparison to the slapdash sky above her, which suggests that natural beauty is nothing compared to the stony perfection of the gods. Following the path of Teucer’s arrow through the following rooms, we find the ideal nude transforming into flesh and, rather soon after, into formalism. Herbert Drapper’s Icarus (1898) is a sensual rather than athletic vision of male beauty. Across the room ropes cut into the flesh of a maiden in John Everett Millais’s The knight errant (1870); one can almost feel her skin twist and quiver as those bonds are cut by her knight errant.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.