The Measure of a Man ★★★★

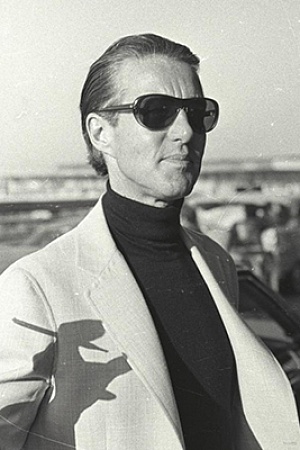

French writer-director Stéphane Brizé's The Measure of a Man (La loi du marché), looks at first to be a character study with a quasi-documentary feel, then takes a disconcerting turn. At its centre is Vincent Lindon (Welcome [2009], Mademoiselle Chambon [2009]), a robust, often demonstrative actor who is also capable of surprising restraint. In The Measure of a Man, for which he won best actor at Cannes in 2015, he gives a subdued, beautifully judged depiction of a middle-aged man grappling with a situation that seems designed to reinforce in him a sense of defeat.

This is Lindon's third film with Brizé. In The Measure of a Man, his character, Thierry, is in his early fifties and worked as a machine tools operator. He has been made redundant, and after almost a year of unemployment inducted into a bureaucratic system that appears to be supportive, but is gradually wearing him down by submitting him to a series of demoralising ordeals. Lindon plays him with a downcast gaze and a kind of stoic determination in the face of the obstacles and obligations imposed on him.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.