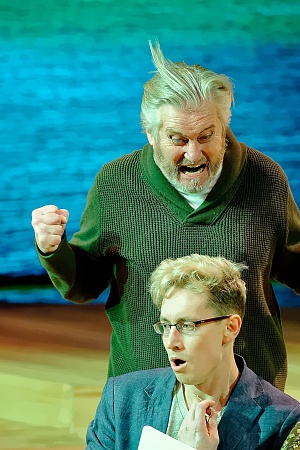

Betrayal (Melbourne Theatre Company)

The gestation of Harold Pinter’s fearsome, hilarious plays was often as interesting as his celebrated dramatic pauses. Betrayal, from 1978, is a good example. Though Pinter was then engaged in an affair with Lady Antonia Fraser that would end his marriage to Vivien Merchant – Pinter’s muse and the creator of many of his great female characters – Betrayal was prompted (the MTC program tells us) by an earlier affair with television presenter Joan Bakewell. She learned this when Pinter sent her the manuscript of the play, as he always did. ‘[P]age by page I began to realise that the plot echoed my own life. I just sat and stared at the copy in my hand, my head empty of thought; just an appalled sense that my life was being raked over.’ (Pinter’s biographer, Michael Billington, discusses the affair here, in an interview with Fiona Gruber via MTC talks.)

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.