Dion Kagan reviews Under the Skin

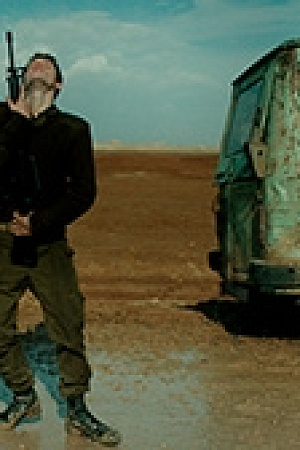

U nder the Skin is adapted from Michael Faber’s eponymous speculative fiction novel (2000) in which an alien disguised as an attractive woman hunts hitchhikers in the Scottish highlands. Once she has determined that a man is appropriate prey, she drugs him and delivers him to a subterranean abattoir hidden beneath a farm where, in a disturbing allegorisation of factory farming, he is castrated, fattened up like foie gras, and prepared for shipment back to the alien home planet where human flesh is an expensive delicacy. This adaptation of Faber’s novel is the long-anticipated third feature film from director Jonathan Glazer.

It has been a decade since his last, Birth (2004), an abstruse psycho-spiritual melodrama in which Nicole Kidman played a woman who comes to believe her late husband has been reincarnated as a young boy. Though working with recognisable sci-fi, thriller, and horror tropes, Glazer’s latest film, with Scarlett Johansson as the extraterrestrial serial killer, has the pulses and textures of something else, something cinematically alien. Under the Skin, like Birth, radically holds back on exposition and reinvents genre in a manner that will both fascinate and frustrate audiences.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.