kith and kin

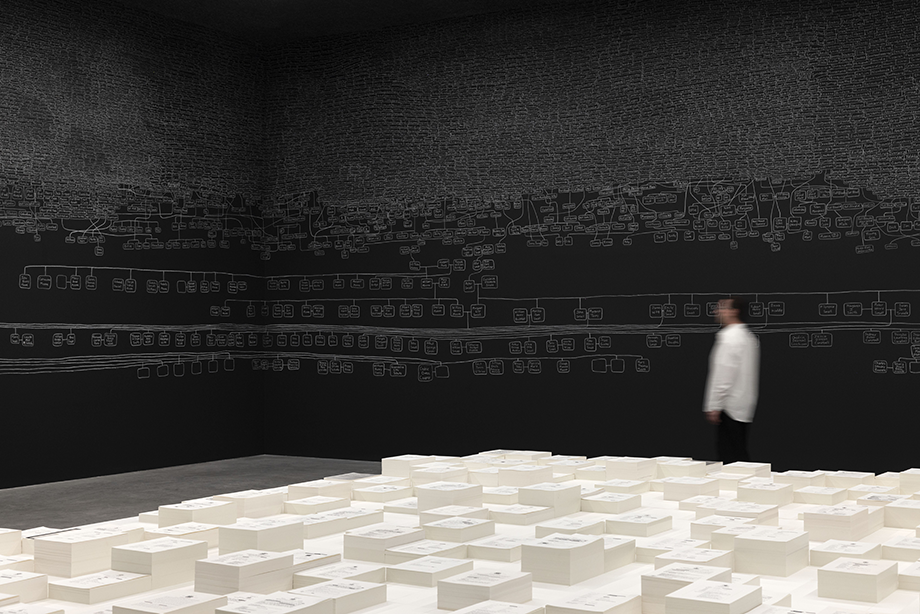

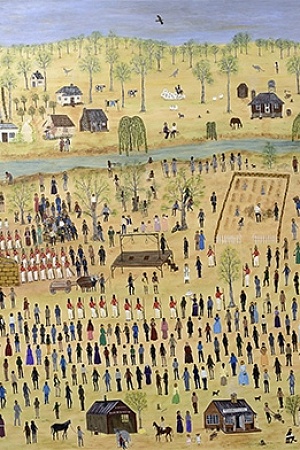

Archie Moore’s kith and kin is an immersive, dark installation created within a black-painted building – a replica of the Australian pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale – that itself sits inside a voluminous wing of Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA). The ‘pavilion’ becomes its own discrete space. An adjacent high window allows natural sunlight and views of the sky. In Venice, the doors opened to the canal; within GOMA, this sky view is as close as the installation gets to nature. Not far from the installation, however, you can overlook Maiwar/the Brisbane River; water flowing around the globe connects these two places. Once inside the exhibition space, your eyes gradually adjust to the darkness. From the darkness appears black chalkboard walls on a scale that dwarfs viewers, a celestial diagrammatic, linked structure hand-drawn in white, and dark concrete floors. Its psychological impact is more slowly felt. The meditative qualities of the room drive a shift in perceptions.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.