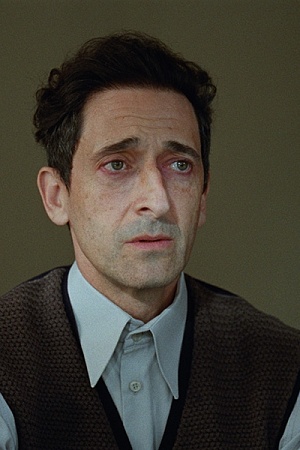

The Critic

The Critic begins with a voice-over in Ian McKellen’s gravelly yet sonorous tones. After defining the term ‘critic’ (‘judge’, according to its Latin and Greek etymology), he declares, ‘The drama critic is feared and reviled for the judgement he must bring, but the truth is imperative, the critic must be cold and perfectly alone. Only the greats are remembered.’ This grandiose statement indicates just how seriously McKellen’s character, theatre critic Jimmy Erskine, takes his craft. Erskine’s megalomaniacal attachment to his vocation, the essence of his identity, is the force that drives him to commit many egregious deeds in this film.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.