Kandinsky

', Paris 1936, photo Boris Lipnitzki © Boris Lipnitzki Roger-Viollet.png)

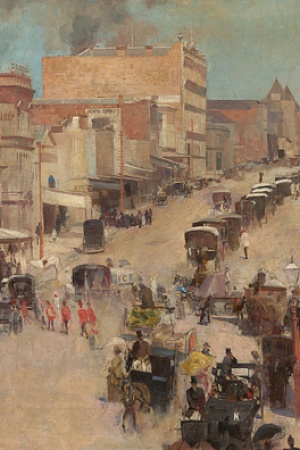

We can all be grateful for Kandinsky, this summer’s main exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. It is a strong and balanced show by the most influential among the early practitioners of modern abstract art. There are four main collections of Kandinsky’s work worldwide, but the best one belongs to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. It was formed from the late 1920s by Baroness Hilla von Rebay, a German artist advising one of America’s richest men, the Philadelphian-born mining magnate Guggenheim. Friends of the artist, in 1939 they founded the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, whose collections, two decades later, were housed in the celebrated spiral building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

What we see in the Sydney gallery is about half of the original eighty-five works from the Guggenheim’s Vasily Kandinsky, Around the Circle, the latest of its periodic in-house displays. Like the Matisse exhibition from the Pompidou in late 2021, the AGNSW’s loan show draws from just one source. It is not the result of active, formative curating from multiple sources so much as negotiating a large rental fee (paid with state government money), shipping and hanging expertly, and publicising (though public programs seem lacking in Kandinsky’s case). Such single-source shows are a favourite practice of Australian state museums, and rarely have much intellectual heft. Yet it continues to surprise me that great overseas museums are willing to risk their treasures in this way. Government indemnity schemes and non-seizure protocols provide some surety, while the practice of transporting the works in four or five separate freight planes distributes the risk.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.