Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles: The power of the reader’s mind over a universe of death

Yale University Press, US$35 hb, 663 pp

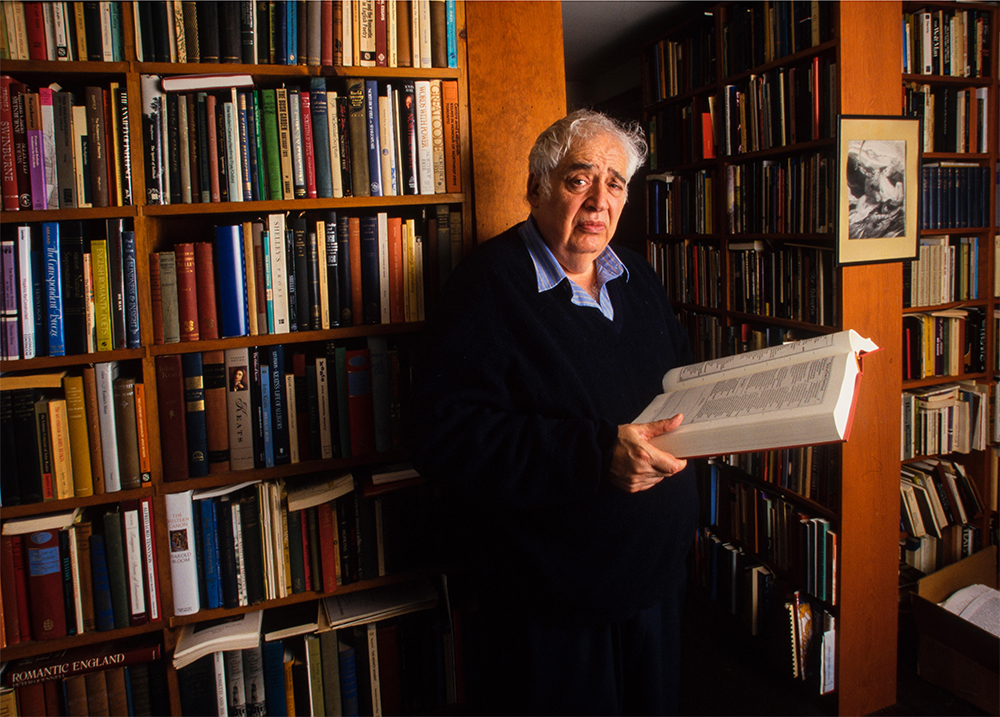

The high priest

Listen to this article read by its author.

Harold Bloom died in 2019 at the age of eighty-nine. Always prolific, he continued working until the very end. Throughout his final book, he digresses at regular intervals to record the date, note his advanced age, and allude to his failing health. At one point, he reveals that he is dictating from a hospital chair.

Could a book composed under such circumstances be about anything other than death? Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles: The power of the reader’s mind over a universe of death, the prolix title of which combines an instantly recognisable line from Shakespeare with a less obvious reference to Milton, can certainly be read as Bloom’s attempt to bring his career full circle. In its pages, the venerable literary critic presents us with his final reflections on a select group of canonical poets (Dante, Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Keats, Tennyson, Browning, Whitman, Lawrence, Frost, Stevens, Crane). He also, pointedly, returns to the subjects of his earliest critical studies (Shelley, Blake, Yeats) and includes a lone chapter on Freud, whose ideas he adapted into his idiosyncratic theories of literary influence and canon formation.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comments (3)

I am not an ‘academician’, which is perhaps why I am not at all frightened by Bloom’s ideas; I simply find them implausible. The breadth of his reading is not the issue, nor is it in question. My objection is the narrowness of his interpretative focus and the cloistered view of literature he advanced. I trust I am not misunderstanding Professor Barbarese when I take his claim about the undemocratic nature of art to be affirming the notion that all writers are not created equal. I suppose there is something a bit undemocratic about the fact most of us will never be as good at writing poetry as Shelley. But art is democratic in the sense that it is available to everyone and addresses a common reality. One can only imagine that the author of ‘The Mask of Anarchy’ would be astonished at the suggestion that poetry has no politics. As for Yeats’s claim that intellectual freedom and democracy are incompatible, I respectfully submit that it is complete nonsense.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.