The gold standard

February 8 will mark the centenary of the birth of Francis Webb (1925-73). Many will ask ‘Francis who?’ as I did at the start of my PhD on Christian mysticism in Australian poetry, when Petra White told me, ‘You have to read Francis Webb.’ I soon found myself reading the 1969 edition of Webb’s Collected Poems in a Richmond café. It was a sturdy, well-thumbed Angus & Robertson hardback with a purple, pink, and white cover bearing a quote from British poet and critic Sir Herbert Read: ‘A poet whose power, maturity and universality are immediately evident.’ In his five-page preface, Read examined Webb’s debts to Robert Browning, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Kenneth Slessor, before concluding:

From the beginning, Webb has been concerned with the same tragic problems as Rilke, Eliot, Pasternak and, to mention a contemporary who presents a close parallel, Robert Lowell. I cannot, after long meditation on his verse, place his achievement on a level lower than that suggested by these names.

Come on, I scoffed with the inferiority complex my culture had instilled in me. This guy’s an Australian!

It didn’t take long before I experienced my ‘Webb moment’, something I have seen in so many readers since. For me, it came in the fourth poem, ‘Cap and Bells’ (1945), set on a train over that great symbol of Australian modernity, the Sydney Harbour Bridge, in World War II, when the poet was around nineteen:

Tonight the stars are yellow sparks

Dashed out from the moon’s hot steel;

And for me, now, no menace lurks

In this darkness crannied by lights; nor do I feel

A trace of the old loneliness here in this crowded train;

While, far below me, each naked light trails a sabre

Of blue steel over the grave great peace of the harbour.

I wasn’t so much struck by one element of this stanza as by all the elements put together: the arresting imagery and atmospherics, wandering line length and slant rhymes, which create a yearning, incantatory tone, plus a classic Webb theme in the search for higher peace imperilled by an ephemeral threat he can defeat, but not escape. Swept up in the hubbub of Australian modernity, Webb declares himself to be radically pre-modern: ‘I have chosen the little, obscure way / In the dim, shouting vortex; I have taken / A fool’s power in his cap and bells …’ Webb compares his art to the skull of Hamlet’s famous fool, ‘a blunt shell of Yorick, that laughs for ever and ever’.

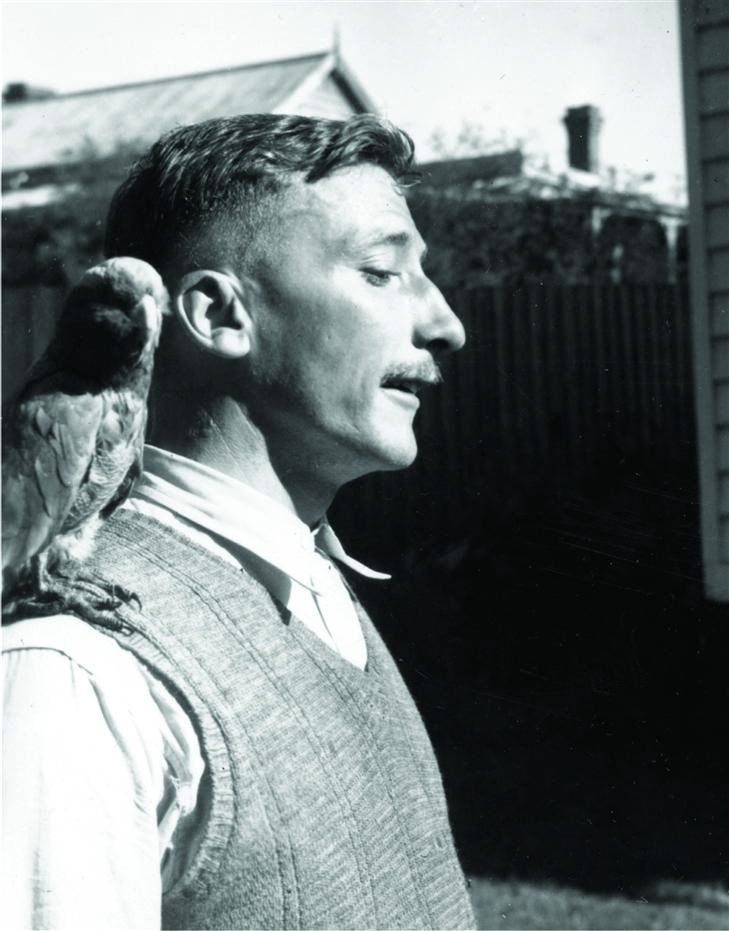

How on earth could a teenager pen this? On top of the artistic bravura, I could see Webb in conversation with Shakespeare, W.B. Yeats’s ‘The Cap and Bells’, and his namesake St Francis of Assisi, the twelfth-century mystic sometimes known as ‘the fool of God’, founder of the Franciscan Order and composer of Cantico di Frate Sole (‘Canticle to Brother Sun’). Yet there was also a deeper personal mythology that intrigued me. In Michael Griffith’s seminal biography, God’s Fool: The life and poetry of Francis Webb (1991), I discovered what ‘the old loneliness’ really was. With his three sisters, Webb was raised by his paternal grandparents in North Sydney as ‘a devout, but not puritanical Catholic’, as he later described it. He was a popular, sandy-haired boy, good at middle-distance running, swimming, and sailing. His love for fine art, classical music, and literature was as obvious as his instinctive resistance to any perceived cruelty or injustice, even if it brought him into conflict with others.

Was the poet born or made? There is a case for the latter in the loss of Webb’s parents. His mother, Hazel Foy, a singer from the famous family behind Foy’s Department Stores, died from pneumonia when Webb was two. Webb’s father, musical performer and piano importer Claude Webb-Wagg, returned to his home city of Sydney so that his parents could help raise Mavis, Claudia, Francis, and Leonie. His grief led to a breakdown that saw him separated (by his own decree) from the children at Callan Park Mental Hospital until his death in 1945. The children needed a myth and their grandmother, now shortened to ‘Ma’, provided it. She told them that God had taken their mother to be the brightest star in the sky, but that their father was lost without her singing and had become The Wandering Star. Webb tried to reach them both through his own music. His earliest poems include a spate of nocturnes, which tease at ‘another wanderer’ in ‘one night’s spacious years’ (‘Palace of Dreams’, 1942) and a ‘careless singer’ (‘Cap and Bells’, 1945). Later, this became explicit in ‘Hospital Night’ (1961): ‘that star, / Housed in glory, yet always a wanderer. / It is pain, truth, it is you, my father, beloved friend …’

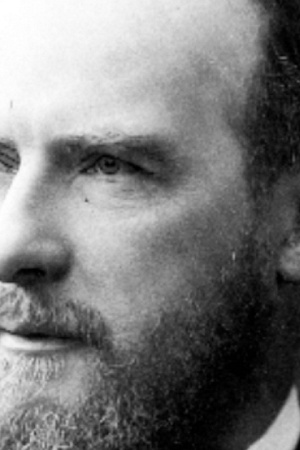

Francis Webb with his bird George, 1950 (courtesy of Claudia Snell)

Francis Webb with his bird George, 1950 (courtesy of Claudia Snell)

By the time I got to him, Webb had been out of print since the 1991 Selected Poems, Cap and Bells, edited by Michael Griffith and James McGlade. I was astonished at this, but astonished twice over when I read the reactions of other luminaries of his era and since. Although Webb never met Judith Wright, she was a talismanic poet for him. In ‘Crucifixion of the Mind’, her review of his fourth collection, Socrates and Other Poems (1961), Wright declared ‘He’s done so much suffering for me and I’ve read him so much and I think that’s what poetry is for.’ Webb was simultaneously the youngest of the postwar generation and the oldest of the 1960s-1970s generation. His work closed the era-defining anthology New Impulses in Australian Poetry (1968). Gwen Harwood, Les Murray, Bruce Beaver, and Robert Adamson became declared Webb fans, the last composing seven poems in his honour. A third generation followed in the 1990s, most obviously in the character of ‘Frank’ in Dorothy Porter’s verse novel What a Piece of Work (1999).

For well over a decade, I have taught my edition of Webb’s Collected Poems (2011) to students at Macquarie University, many with the eBook installed on their devices. I have also run the annual Francis Webb Reading at Willoughby Library in Chatswood, where the poet’s personal book and art collection are held. Webb’s artistry has always been respected, but I have seen sentiment shift recently because of his ground-breaking depictions of mental health. Indeed, ‘On First Hearing a Cuckoo’ (1952) and ‘A Death at Winson Green’ (1955) are Australia’s first ‘asylum poems’ by a major poet. They represent a quantum leap in how mental health was represented in Australian poetry. No one else of Webb’s stature had ever asked Australian readers to enter the daily life of a mental patient. ‘On First Hearing a Cuckoo’ does this abstractly, suggesting some kind of English hospital with cuckoo birds outside, but it is left to readers to join the dots, and reviewers of the era never did. ‘A Death at Winson Green’, first published in the Times Literary Supplement in 1955, is reproduced here because it is more unequivocal: ‘Visitors’ Day: the graven perpetual smile, / String-bags agape, and pity’s laundered glove.’ The poet is among ‘The last of the heathens’ who ‘shuffles down the aisle, / Dark glass to a beauty which we hate and love’.

What happened to this golden boy of Australian letters? While still a schoolboy at Christan Brothers College in Lewisham, Webb’s ‘Palace of Dreams’ was selected for The Bulletin by Douglas Stewart, poet and powerful editor of its ‘Red Page’. Only a few years after he returned from RAAF training in Canada, Webb’s first collection, A Drum for Ben Boyd (1948), was published by Angus & Robertson, with illustrations by Norman Lindsay, who became a supporter in tandem with Stewart. In the tiny, Sydney-centric poetry world of the 1940s, Webb did as well as any young poet could dream of, winning the Grace Leven Prize and befriending other young poets, such as Rosemary Dobson. In 1949, during a second stint in Canada, Webb fell out with Lindsay by correspondence, believing the latter’s attacks on ‘corrupt’ and ‘abstract’ modernists Webb loved (T.S. Eliot, Hart Crane, Gertrude Stein, Dylan Thomas) were veiled attacks on himself, given that Lindsay was reading his latest pieces. ‘I am not following any trend,’ a twenty-four-year-old Webb fired back. ‘I have never before had greater confidence in myself and in my work, and I tell you bluntly that I don’t at this moment give a god-damn whether the Bulletin wants me or not.’

The Bulletin was secular, brawny, and heroic, but Webb found himself profoundly impacted by an American Catholic contemporary in Robert Lowell. He recalled that ‘I knew that now my poetry must openly acknowledge God and the Redemption.’ Webb decided to return to Australia via London. Before his boat sailed, he read a commentary on Freud’s theories of the subconscious, the libido, infant sexuality, and masochism. To counter Lindsay’s apparent charges of ‘corruption’, Webb interrogated himself and found endless moral faults, including cowardice for not challenging Lindsay’s anti-Semitism. At sea, his torment intensified as he paced the deck for three nights holding a Lindsay sketch for his second collection, Leichhardt in Theatre (1952), before he tore it up and flung the pieces into the Atlantic. Webb disembarked in England in a terrible state, attempted suicide with a razor, and was hospitalised in Surrey, where ‘On First Hearing a Cuckoo’ is set. A second period in England, from 1953 until his final return to Australia in 1960, led to his institutionalisation for ‘persecution mania’ and, later, schizophrenia, though Webb never accepted any one diagnosis.

From his first breakdown in his mid-twenties, Webb wrote about life ‘inside’ and treatments such as ECT and pneumo-encephalographs. He challenged Australian and British society to see the human beings behind institutional walls from their ‘world of commonsense’ as he later put it in ‘Ward Two’ (1964), set in Parramatta Psychiatric Hospital. Webb also leant into his mystical Catholicism, from ‘The Canticle’ to elegies for child and child-aligned saints (‘Lament for St Maria Goretti’, ‘St Therese and the Child’). Childhood innocence, unsurprisingly, was a Webb obsession, foundational not just to his own mythology, but also to his vision of Christ’s Incarnation. ‘Five Days Old’ (1961) combines these two via Webb’s experience of holding a newborn baby (and being trusted to do so, by one of his more sympathetic English doctors). This shows the quieter, more lyrical Webb who is ‘launched upon sacred seas, / Humbly and utterly lost / In the mystery of creation’.

This is another side of Webb’s legacy, the transcendent side to complement the socially minded one, although for Webb they could not be completely disentangled. It extended to his centring of Aboriginal pre-colonial presence and holiness in two anti-colonial masterpieces, ‘End of the Picnic’ and ‘Balls Head Again’ (both 1953), and in poems defending postwar migrants.

It is high time more Australians knew of this genius in their midst, whose reputation has been unfairly impacted by the stigma of the ‘mad poet’ who is thus incomprehensible and corrupting, to be kept away from children (including on the national curriculum). Most Australian poets across the generations saw him very differently. After Webb died from a coronary occlusion in November 1973 (likely exacerbated by heavy smoking and psychiatric drugs), Les Murray’s obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald called him ‘the gold standard by which complex poetic language has been judged … a master of last lines, of last stanzas and final phrases’. As Francis Webb turns one hundred, we can all reflect on the brilliance, urgency, and humanity of his work, and take up the challenge to help new readers have their ‘Francis Webb moment’ by engaging with the essays, podcasts, readings, and social media posts emerging this year in his honour.

This is one of a series of ABR articles being funded by Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comment (1)

https://uwap.uwa.edu.au/blogs/marginalia/centenary-of-major-australian-poet-francis-webb

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.