Sylvia Martin

Letters to the Editor - March 2007

Dear Editor,

I welcomed Barry Jones’s feisty response (February 2007) to my review of his autobiography, A Thinking Reed (December 2006–January 2007). Such autobiographies, the reviews and the commentaries on them are the first drafts of history, and such debates will be valuable to later and more dispassionate historians. Apart from some sardonic barbs, which I may well deserve, he seems to have only one substantive quarrel with the review and that is with my critical assessment of his performance as science minister in the Hawke government.

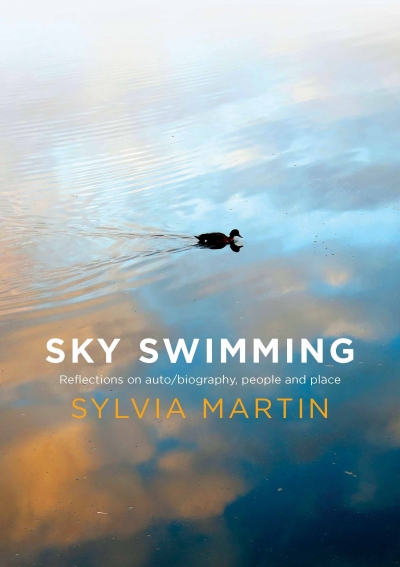

... (read more)Sky Swimming: Reflection on auto/biography, people and place by Sylvia Martin

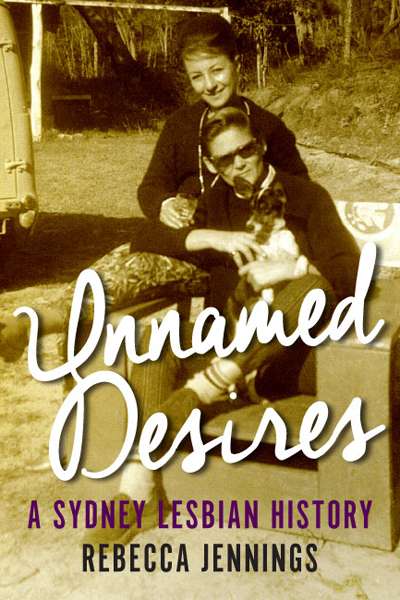

Unnamed Desires: A Sydney Lesbian History by Rebecca Jennings

ABR welcomes letters from our readers. Correspondents should note that letters may be edited. Letters and emails must reach us by the middle of the current month, and must include a telephone number for verification.

... (read more)