Darleen Bungey

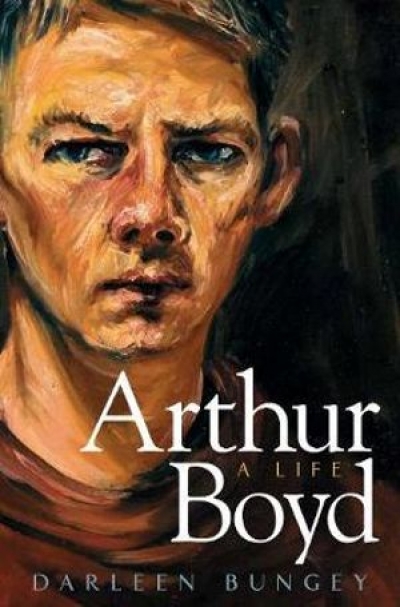

Brenda Niall (ABR, March 2008) feels ‘confronted’ by an ‘extraordinary claim’ in my book, Arthur Boyd: A Life. The two sentences that caused her consternation are: ‘Yet it seems that ultimately Martin’s spirit was crushed. His broken body would be discovered in the Blue Nuns’ gardens, lying where it had fallen, below his hospital window.’ Niall complains that I did not ask her opinion about Martin Boyd’s likely suicide. Since this was not included in her biography, Martin Boyd: A Life ( 1988), I believed she knew nothing about it. I understand how annoying it must be to write a full biography of a person and learn later of information that may have been available, but Niall’s defensive and plaintive attack demands a response.

... (read more)