Appalling as it sounds, many of us never out-grow our childhood personae. Although people become adept at concealing their petulance and insecurities behind adult façades, among siblings and parents they revert to type, unable to resist lifelong family roles and patterns.

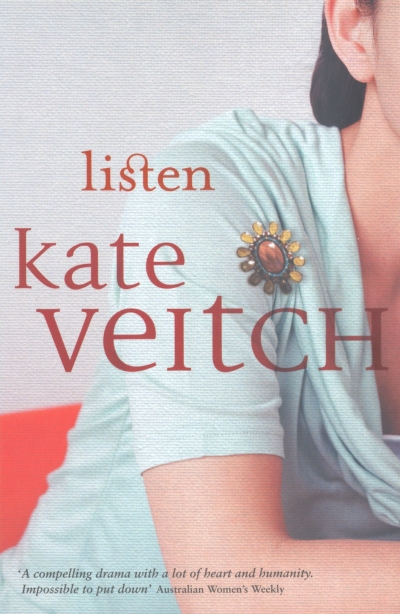

Kate Veitch’s first novel, Listen, is a vivid dissection of a fractured family. Forty years after a young mother of four – the unexpectedly likeable Rosemarie – has abandoned her children and husband one Christmas Eve to escape Melbourne suburbia for Swinging London, the anguish of her flight still reverberates for her children, manifesting itself in different ways. Rosemarie’s eldest daughter was effectively thrust into premature motherhood at the age of thirteen, due partly to her father’s benign neglect. Deborah resents the injustices and sacrifices of her adolescence, when she was consumed with raising her siblings. She is constantly irritable with her husband, and unable to comprehend her teenage daughter Olivia’s preference for animals to humans. Her anger drives a wedge between herself and her family.

...

(read more)