Patrick White

I can’t let you have my ‘papers’ because I don’t keep any. My mss are destroyed as soon as the books are printed. I put very little into notebooks, don’t keep my friends’ letters … and anything unfinished when I die is to be burnt. The final versions of my books are what I want people to see …

(Patrick White, reply to Dr George Chandler, Director General, 9 April 1977, National Library of Australia, MS 8469)

... (read more)Patrick White had rather more success than Henry James with his plays – though that is not saying much. James’s attempt in the 1890s to conquer the London stage was a theatrical and personal disaster, but has, remarkably, provoked two recent novels, Colm Tóibín’s The Master and David Lodge’s Author, Author. The plays were no great loss, and it was to our ultimate benefit that James returned his creative energy to the novel.

... (read more)John Clancy does a number of curious things in his new novel. One of them is to put Patrick White’s Voss into the hands of his heroine. Laura is in Year 12. Her teacher, Miss Temple, happens to find a copy of Voss when they are together on a school excursion to Alice Springs. Laura immediately warms to the book. She is a remarkable young woman, sensitive and resourceful. Destined to study medicine, she has literary gifts as well. People offer her jobs at places where others her age are queuing for work. One of her reasons for going on the school excursion, where she helps supervise a group of Year 7 and 8 children, is that she is recovering from the termination of her relationship with Patrick, her slightly older beau.

... (read more)Some years ago the poet John Forbes was addressing himself to that national monument, Les Murray, and he had occasion to remark, ‘The trouble with vernacular republics is that they presuppose that the kingdom of correct usage is elsewhere.’ It was, I suppose, designed to highlight the fact that the homespun qualities of the Bard from Bunyah were dependent on an awareness of the metropolitan style Murray willed himself to transgress and that there was an inverted dandiness, if not a pedantry, in all that Boeotian ballyhoo. It does not seem to me a remotely fair remark but it is a good epigram notwithstanding and it takes on a range of meanings depending on what light you look at it in. Presumably Forbes thought, or feigned to think, that Murray’s poetic demotic was a variation on that Colonial Strut which is, in fact, a version of the Cultural Cringe. In any case his words came into my head the other day when I was reading Simon During’s new Oxford monograph about Patrick White.

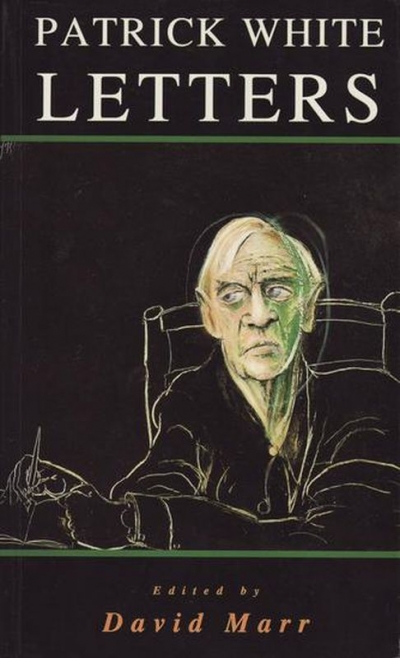

... (read more)Letters turn talking to yourself and to someone else into the same thing. The recipient can’t interrupt, and can’t answer back, at least not yet. Self-obsession is almost a virtue in letters since correspondents who won’t talk about themselves are boring. But letters also make for unreliable autobiography because they’re written out of an understanding not just of what the sender wants to say but also what the recipient needs to hear – and every recipient is different. This is why reading letters not addressed to you is taboo: you invade the privacy of two parties.

... (read more)Collected Plays, Volume II by Patrick White & Collected Plays, Volume II by David Williamson

In a recent interview on ABC radio, the playwright, Stephen Sewell, deplored the lack of revivals of notable Australian plays. Now and then, one of the pioneer playwrights from the first half of the century is honoured briefly in this way, but it is much rarer to find one of the professional companies revisiting the major works of the last twenty-five years. As Sewell implied, this reflects the lack of a strong sense of a tradition of ‘modem classics’ in our theatre.

... (read more)Publishers are like invisible ink. Their imprint is in the mysterious appearance of books on shelves. This explains their obsession with crime novels.

To some authors they appear as good fairies, to others the Brothers Grimm. Publishers can be blamed for pages that fall out (Look ma, a self-exploding paperback!), for a book’s non-appearance at a country town called Ulmere. For appearing too early or too late for review. For a book being reviewed badly, and thus its non-appearance – in shops, newspapers and prized shortlistings.

As an author, it’s good therapy to blame someone and there’s nothing more cleansing than to blame a publisher. I know, because I’ve done it myself. A literary absolution feels good the whole day through.

... (read more)'Patrick White and Australian Writing: Towards a new Asian Pacific literature' by Zhu Jiongqiang

Professor Zhu Jiongqiang works in the Department of Foreign Languages at Hangzhou University in the People’s Republic of China. A specialist in Australian literature, he has translated Patrick White’s The Eye of the Storm into Chinese, and has written extensively on Australian writing in both Chinese and English. In this translated extract from a discussion about the history and current trends in Australian literature, Professor Zhu places Patrick White in the context of literary schools. He finishes by suggesting that new styles of writing are emerging from the kinds of writing introduced by White and that a new Asian Pacific culture – the culture of Australia – is coming into prominence.

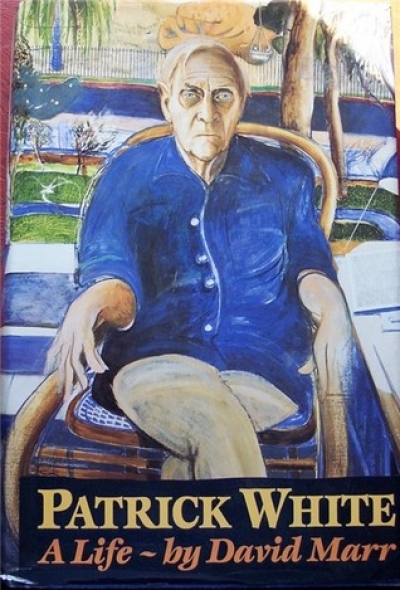

From the end of the Second World War, the most illustrious and noteworthy writer in Australia was Patrick White. Someone said that contemporary Australian literature is Patrick White and there is some truth in this remark.

... (read more)If before the 1890s, books had been judged by their dust jackets, most would have been considered uniformly dull, or indecently attired. Dust jackets appeared first in 1833 to protect the recently introduced cloth casings as they made their progress from printery to publisher’s warehouse, on to booksellers and then to library shelves, at which stage the wrappings were usually thrown away. Those earliest dust jackets could be blank or printed with the title as well as the names of the author and publisher on the front, or notices about other volumes on the back panel.

... (read more)Writing to Geoffrey Dutton in 1969, Patrick White confesses: ‘All my life I have been rather bored, and I suppose in desperation I have been inclined to weave these fantasies in which I become more “involved”. Ignoble, au fond, but there have been a few results.’

... (read more)