Fiction

Food is often used as a metaphor for a range of emotions, and this device is underscored in Simone Lazaroo’s fourth book. The title alludes to the idea of nourishment as a substitute for love, sex and religion. Indeed, the protagonist, Malaysian Perpetua de Mello, is a chef at a four-and-a-half-star Balinese tourist resort, the Elsewhere Hotel. Although the slogan in its promotional flyer encourages visitors to ‘Find yourself at Elsewhere Hotel’, most of the guests have come to lose themselves, to seek consolation from whatever ails them back home. Though undated, the novel is set soon after the bombing attacks in Bali; the tremors of the terrorist strikes still reverberate. It depicts a nervous island desperate to attract more tourists, if only to stimulate its damaged economy. There has even been a directive in the local media to smile more at foreigners.

... (read more)World War I is lodged in the minds of Australians with mythic power. Chris Womersley, in plain and startling yet tender and lyrical prose, has constructed a moving narrative that opens up the wounds of war, laying bare the events that pre-date the conflict and reach forward into the collective memory. I was reminded of A.S. Byatt’s recent novel The Children’s Book (2009), which also foregrounds in poetic language the Great War and etches forever the horror of broken bodies and minds on the consciousness of its readers.

... (read more)''Tirra Lirra' and Beyond - Jessica Anderson’s truthful fictions' by Susan Sheridan

According to the author’s note at the end of The Grand Hotel, this will probably be the last of his stories to be set in fictional Mangowak, a coastal town in south-western Victoria. The first, The Patron Saint of Eels (2005), won the 2006 Australian Literature Society Gold Medal. The second, Ron McCoy’s Sea of Diamonds (2007), was shortlisted for the 2008 New South Wales Premier’s Prize for Fiction.

... (read more)The Book of Human Skin details the trials and tribulations of an innocent Venetian noblewoman named Marcella Fasan, a girl ‘so sinned agin tis like Job in a dress’, Gianni delle Boccole, loyal family servant and bad speller, explains. Marcella’s principal antagonist is her older brother Minguillo, who, out of filial jealousy and a desire to be the sole heir to the family’s New World fortune in silver, makes her a prisoner, a cripple, a madwoman, and a nun. Think Jacobean tragedy meets Gothic novel, then add some – namely a crazy Peruvian nun called Sor Loreta, who, in between fasting and self-flagellation marathons, terrorises the saner sisters at the convent of Santa Catalina in Arequipa. It is these four characters – Gianni, Marcella, Minguillo, Sor Loreta, plus the kindly Doctor Santo Aldobrandini, a specialist in skin and its maladies – who, unbeknown to one another, take turns narrating this novel.

... (read more)John Birmingham’s After America is the second book in what is clearly intended to be a trilogy of page-turners – a follow-up to his Axis of Time trilogy, the swashbuckling alternative history which saw a US carrier battle group transported back in time to the middle of World War II. After America, the sequel to Without Warning (2009), is set in a decidedly dystopian alternative present, the result of a mysterious energy wave that wipes out most of the human and animal life forms in North America in 2003. As one might expect, chaos ensues. A global ecological catastrophe has accompanied the human disappearance, a civil engineer from Seattle (the only big US city to survive the wave) has been elected president, Israel has launched nuclear strikes on its Middle East neighbours, and groups of well-organised pirates from Lagos have taken over New York City.

... (read more)At its best, popular fiction is almost cinematic. As readers, we know what to expect but still gasp in awe as the rug is pulled from under us in pursuit of thrills, chills, and narrative twists. Honey Brown’s second novel, The Good Daughter, is a fine example of the modern ethos. It reads like a classic girl-gone-bad screenplay. Rebecca Toyer, from the wrong side of the tracks, meets Zach Kincaid, a rich boy with skeletons in his closet. They are drawn together, but family secrets threaten to drive them apart. When Zach’s mother goes missing, Rebecca is implicated in her disappearance. During the course of the narrative, she encounters drug dealers, crooked cops, and her fair share of sex, lies, and betrayal. Zach struggles to cope with his family legacy. From early on, he is the powder keg that threatens to ignite the book’s narrative.

... (read more)When Miranda Ophelia Sinclair, ‘Moss’ to her friends, discovers a document featuring the name of her heretofore unknown father, she sets out to find him and to discover her genetic roots. Her complicated family history is gradually exposed when she finds her father, Finn, living as a near-recluse in a town called Opportunity. Finn’s next-door neighbour is Lily Pargetter: aged, lonely, haunted by memories and ghosts. Her nephew, Sandy, is a middle-aged man-child, ineffectual but harmless. This eccentric cast of characters could easily hold its own against Alexander McCall Smith’s creations; however, Evans sets her protagonists on a predictable and fairly scripted path, resulting in a message-driven narrative.

... (read more)Patrick White got it wrong. European Australians have never been driven to find spiritual meaning through physical deprivation in the deserts of the interior. Their passion has been for housing and construction, matched by their devoted gourmandising. White declared that in Voss he was trying to teach a nation of timid city dwellers that there was more to life than material comfort and ‘cake and steak’. He did take himself rather seriously.

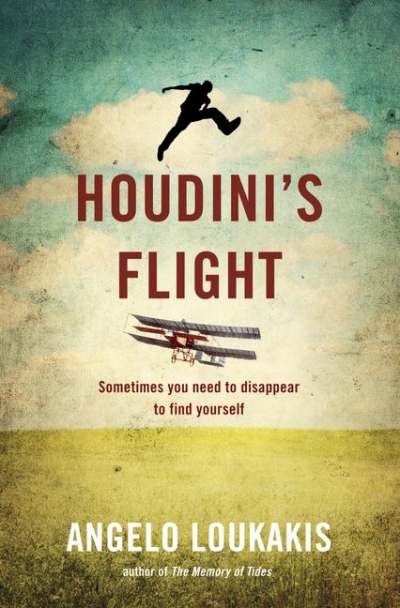

... (read more)During Harry Houdini’s 1910 visit, the famous escapologist claimed to be the first person to achieve powered, controlled flight in Australia. In Houdini’s Flight, Angelo Loukakis uses these bare details as the backdrop for a modern tale about a more modest achiever, Terry Voulos. A second-generation Greek-Australian, Terry confronts, almost in slow motion, a personal crisis that initially seems caused by his own stuttering approach to life. Whereas Houdini descends into water to release himself from heavy chains, Terry must break free from his own limitations to revitalise his life, his attitudes, his marriage to Jenny and his bond with his son, Ricky.

... (read more)