Harvard University Press

The Keats Brothers: The life of John and George by Denise Gigante

by William Christie •

Charles Dickens by Claire Tomalin & Becoming Dickens by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

by Evelyn Juers •

Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach by Martha C. Nussbaum

by Belinda Probert •

The Decline and Fall of the American Republic by Bruce Ackerman

by Alison Broinowski •

The Classical Tradition by Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most, and Salvatore Settis

by Christopher Allen •

Playing the Numbers: Gambling in Harlem between the Wars by Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson and Graham White

by David Goodman •

Settler Sovereignty: Jurisdiction and indigenous people in America and Australia, 1788–1836 by Lisa Ford

by Henry Reynolds •

A New Literary History of America edited by Greil Marcus and Werner Sollors

by James Ley •

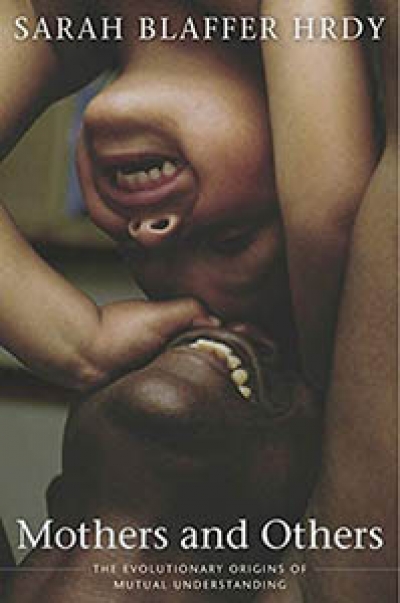

Mothers and Others: The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding by Sarah Blaffer Hrdy

by Michael Gilding •