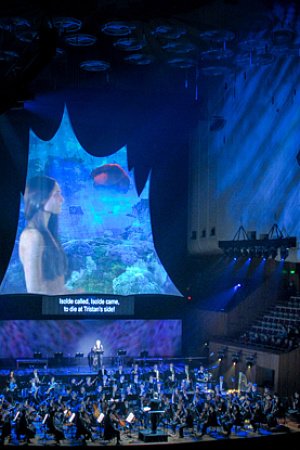

The Flying Dutchman (Victorian Opera)

For many of us – those of us not in the Farnham faction – this was our first visit to the Palais Theatre in three decades. (It has mostly been used as a rock venue since the Australian Opera decamped.) So there was much anticipation before the opening night of Victorian Opera’s The Flying Dutchman, perhaps the most ambitious production in the company’s ten-year history.

The Palais, it must be said, is showing its age (it was rebuilt in the 1920s after a fire). Not even Joan Sutherland (who sang there many times in the early 1980s) could have hoped to fill the Lounge (a stratospheric dress circle that seats about 2,000 people on its own; the theatre’s total capacity is just under 3,000). Time’s ravages have not impaired the fabulous acoustic. The vast pit, the grand proscenium, the closeness to the stage of the wide, curved Lounge, offer an absorbing theatrical experience. It was great to be back there, fire traps and flaking domes notwithstanding.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.