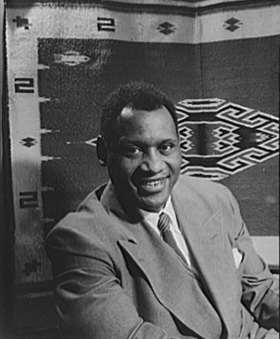

No Way but This: In Search of Paul Robeson

Scribe, $32.99 pb, 304 pp, 9781925321852

No Way but This: In Search of Paul Robeson by Jeff Sparrow

Is it surprising that Jeff Sparrow should write a book on Paul Robeson, the great American singer who was also a civil rights activist, a man of the left, and the most celebrated Othello of the twentieth century? Sparrow is a broadcaster and columnist, but he is also the immediate past editor of Overland, a literary journal dedicated to a mixed diet of – as Billy Bragg might say – pop and progressive politics, a magazine where reports on workers’ rights sit next to think pieces on Kanye West and the 2020 presidential election.

So why not write about Paul Robeson? He was, after all, at one time the most famous African American entertainer on the planet: almost the Kanye of his generation. Indeed, Robeson’s excess of talent still boggles the mind. The son of an escaped slave, he was a football star, a formidable orator, a virtuoso linguist, and a singer and actor of immense power. He fundamentally changed the way the world looked at black performers on stage, and to a lesser extent, on screen. When he played Othello in London in 1930, opposite Peggy Ashcroft, it was the first time that a non-white had played Othello in London since Ira Aldridge in 1825. He reprised the role in 1943 on Broadway with Uta Hagen in a production that still holds the record for the longest-running Shakespeare production in the United States. He was also an impassioned socialist with an instinctive sympathy for the underdog. He campaigned tirelessly for racial equality and the rights of working men and women everywhere. He was an uncompromising opponent of fascism, and toured Spain during the Civil War, singing for Republican troops at Tarazona and in hospitals at Murcia and Benicàssim.

To tell this story – or partially tell it – Sparrow scampers around the world, visiting the places Paul Robeson visited, using key moments in the great man’s life to reflect on a clutch of contemporary hot-button political and cultural issues. From Harlem to London, Cardiff to Barcelona, and then Moscow, Sparrow stays in the same hotels that Robeson stayed in and walks the same streets, searching for traces of a lost spirit, as if there were salvation in emulation.

He visits Robeson’s childhood home near Princeton and discovers that the area no longer seems so run-down or poor. Much has changed for African Americans since Robeson was a boy, but some changes have only ensured that things stay the same. In 1850 there were nearly 900,000 adult men enslaved in America; today, almost one million African American males languish in jail. ‘To put it another way,’ writes Sparrow, ‘more black people were deprived of their liberty in the twenty-first century than at the height of slavery, a comparison absolutely astonishing and deeply depressing.’

In Wales, Sparrow meets a woman who teaches local schoolchildren about Robeson’s special relationship with Welsh mining communities and culture. He admires her project, but is disappointed that her students are not also taught about the socialist ideals Robeson subscribed to. What a shame, he sometimes seems to say, that today Robeson is celebrated for his accomplishments as an artist rather than for his commitment to collectivity.

Paul Robeson as Othello and Uta Hagen as Desdemona, Theatre Guild Production, Broadway, 1943–44 (Wikimedia Commons)There are moments in this book when Sparrow does not seem on top of his material. To take just one example among many: he declares that Othello is ‘the one Shakespearean role marked as non-white’, despite the fact that there is a long interview here with Hugh Quarshie, who played Othello for the Royal Shakespeare Company, but also played Aaron the Moor in the BBC Shakespeare Titus Andronicus (1985).

Paul Robeson as Othello and Uta Hagen as Desdemona, Theatre Guild Production, Broadway, 1943–44 (Wikimedia Commons)There are moments in this book when Sparrow does not seem on top of his material. To take just one example among many: he declares that Othello is ‘the one Shakespearean role marked as non-white’, despite the fact that there is a long interview here with Hugh Quarshie, who played Othello for the Royal Shakespeare Company, but also played Aaron the Moor in the BBC Shakespeare Titus Andronicus (1985).

Slips and misunderstandings like this add to the impression that Jeff Sparrow is more interested in his own anguish over challenges facing the left than he is in Robeson or his historical context. This book takes its place as part of a broader wave of retrospection and soul searching among veterans of the left who are struggling to comprehend activist movements where identity categories loom large, the politics of privilege-checking dominates, and where working-class perspectives are withered away to nothing.

It is against this background that Sparrow points his lesson. After World War II, Robeson became a victim of anti-communist paranoia in the United States. An impenitent Soviet sympathiser, his career was curtailed for more than a decade. For Sparrow, this is the inspirational high point of the Paul Robeson story. The most successful black man of his generation sacrificed it all for the sake of his principles and his vision of a better future, refusing to compromise or concede or in any way scrape for the government bullies.

No Way but This finishes on a melancholy note as Sparrow tours Russia, attempting to fathom Robeson’s admiration for the Soviet system. It is remarkable to think that in 1938 Robeson enrolled his son in a model school in Moscow, where he studied alongside the daughters of Stalin and Molotov. As Sparrow wanders in his heartfelt, gloomy way around the ruins of old gulags, he muses on continuities between Russia then and now.

Paul Robeson in 1942 (photograph by Gordon Parks, Office of War Information, Wikimedia Commons)In the end, Sparrow finds solace in Robeson’s firm belief in a better world to come. He must have started writing this book at a time when it seemed as though America’s first black president would be succeeded by its first female president. Instead, we have Donald Trump, a president whose admiration for Vladimir Putin is an ongoing puzzle. In this context, Sparrow’s final gestures of uplift and hope seem rhetorical.

Paul Robeson in 1942 (photograph by Gordon Parks, Office of War Information, Wikimedia Commons)In the end, Sparrow finds solace in Robeson’s firm belief in a better world to come. He must have started writing this book at a time when it seemed as though America’s first black president would be succeeded by its first female president. Instead, we have Donald Trump, a president whose admiration for Vladimir Putin is an ongoing puzzle. In this context, Sparrow’s final gestures of uplift and hope seem rhetorical.

Robeson may have been blinded by the legacy of American racism and by the monumental sacrifice of the Russians in World War II. Still, it is baffling that he did not denounce the Communist Party in 1956 over Hungary, like Overland’s founding editor Stephen Murray-Smith. It is also terribly sad that in the early 1960s, when black actors like Sidney Poitier were finally conquering Hollywood, Robeson, who should have been their patriarch, was lost in a maze of mental affliction.

![Susan Sheridan reviews ‘Joan Lindsay: The hidden life of the woman who wrote Picnic at Hanging Rock’ by Brenda Niall Joan and Daryl Lindsay at Mulberry Hill (National Trust of Australia [Victoria}, Mulberry Hill [MH4098], courtesy of Text Publishing)](/images/raxo_thumbs/tb-w300-h450-crop-int-2431e1ea35788b1963a98d8d66bf13a5-img.jpg)

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.