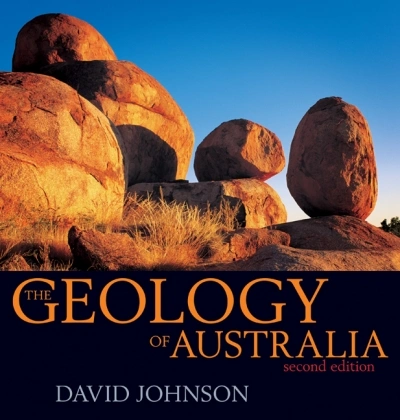

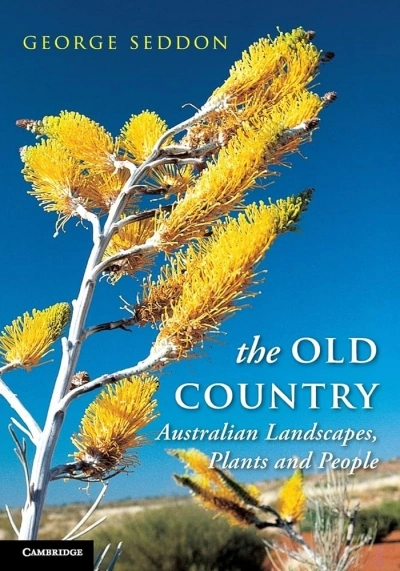

The old country is, by his own admission, George Seddon’s last book. Last books are generally the products of two factors: posthumous recognition of work-in-progress, or a generous sharing of one lifetime’s accumulated wisdom. Happily, this book falls into the latter category. The opening chapter does nothing to jolt this impression; with avuncular ease, Seddon introduces his characters and stories. We sit with Uncle George at the fireside – or more realistically, given the irony of the title, around the campfire. The stream of consciousness is conversational, discursive and often intensely personal. Seddon has a gift for storytelling. While still in the roman numerals of the preface, we have a telling example: ‘The past lies at the author’s feet,’ Seddon observes epigrammatically, his boots juxtaposed over 3.5-billion-year-old stromatolites at Marble Bar in Western Australia’s far north-west. We immediately under-stand that the author’s time frame is very wide indeed. We were half expecting a gardening book – or at least a book about plants, judging from its Dewey classification – but should not be surprised by this un-conventional opening gambit. ‘We live in old landscapes with limited water and soils of low fertility,’ Seddon explains, ‘yet with a rich flora that is adapted to these conditions, as we are not. There is much to learn from it, but we have been slow learners.’

...

(read more)