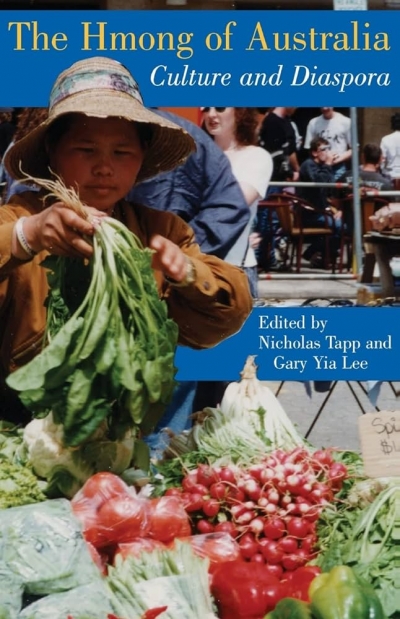

One sun-filled Saturday in spring 2000, I wandered through Salamanca market, in and around the historic sandstone buildings on Hobart’s waterfront. After a long absence, I expected the arts and crafts, antiques, and books amid tourists and the local caffe latte set. What surprised me were stalls of beautiful fresh fruit and vegetables, grown and sold by smiling ethnic Hmong. The bright front cover of The Hmong of Australia zooms into that image of my memory.

It is pleasing to learn from sociologist Roberta Julian that, for Tasmanians, the Hmong ‘symbolise a new openness to Asia’. Yet it is disconcerting to be told: ‘Insofar as the Hmong are accepted as Tasmanians, however, their identity has become commodified, trivialised and marginalised … a superficial Hmong identity.’ Any more so than that of the Han Chinese and Italian vendors, who draw camera-clicking busloads to Melbourne’s Queen Victoria Market? Or that of the colourfully clad Hmong minority in China’s southern Yunnan province, ancestral homeland of the Hmong?

...

(read more)