Craftsman House

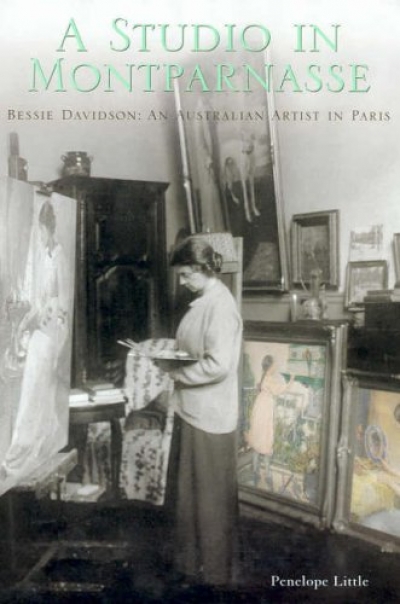

A Studio in Montparnasse: Bessie Davidson, an Australian artist in Paris by Penelope Little

There is no doubt that the state of writing about contemporary Australian art would be in dire straits without the support of Craftsman House. In the past two decades, this small Sydney-based publisher has plugged significant gaps in the field with some of its most influential texts: Vivien Johnson’s ground-breaking work on Australia’s Western Desert painters (1994); Charles Green’s thorough mapping of Australian art since 1970 (Peripheral Vision, 1995); and one of the first, and still most concise, English-language surveys of Soviet and early post-Soviet art, immediately spring to mind. This is not to say that all of these initiatives were limited to the thrall of academia. In collaboration with the magazine Art and Australia, Craftsman House produced a series of monographs on emerging and mid-career Australian artists at a time when their CVs generally hinged on catalogue essays or the occasional review. The effect was complementary: alongside the advocacy of artists such as Janet Laurence, H.J. Wedge and Hossein Valamanesh came the franking of a new wave of important local critics: not just Green and Johnson, but Chris McAuliffe, Paul Carter, Benjamin Genocchio and Ashley Crawford as well.

... (read more)We should no longer marvel at the way art historians are forever finding yet another woman artist to rescue from undeserved obscurity. With Patricia R. McDonald’s tribute to Barbara Tribe we have the work of this eclectic Australian sculptor finally validated in a handsomely produced monograph.

... (read more)