Hyland House

How to Play Netball by Jodie Clark and Kristen Moore & How to Play Cricket by Garrie Hutchinson

by Stella Lees •

My Dear Spencer: The letters of F. J. Gillen to Baldwin Spencer edited by John Mulvaney, Howard Morphy, and Alison Petch

by Barry Hill •

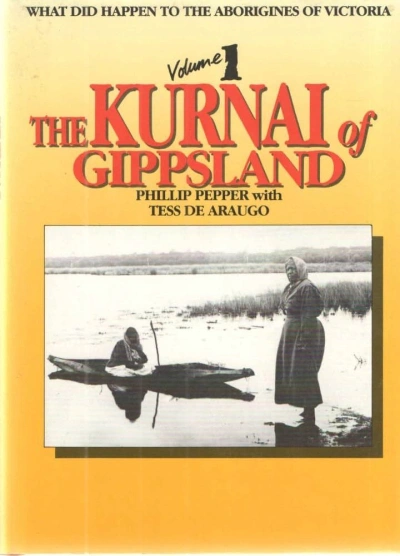

The Kurnai of Gippsland: Volume 1 by Phillip Pepper and Tess De Araugo

by Patrick Morgan •