Elizabeth Jolley

Dear Editor,

Brian Matthews makes an eloquent defence of Manning Clark’s Kristallnacht fantasy, but I was surprised to find myself being drafted as a witness simply because I once said that autobiography is ‘a lying art’ (May 2007). Actually, I can’t remember ever having used quite those words, but, as Brian Matthews well argues, memory plays tricks.

... (read more)Dear Elizabeth,

Well, it seems our long correspondence is over. Actually it ended some years ago, didn’t it? Your last letter to me is dated Christmas Eve 2001. I continued writing to you into the following year, not immediately realising you were unable to reply, even though your later letters spoke of confusion and of unaccountably getting lost in familiar streets.

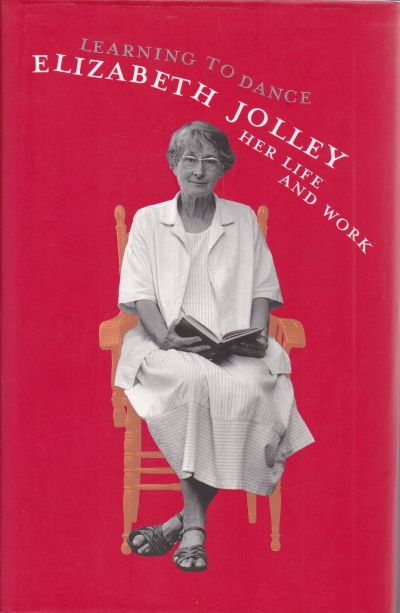

... (read more)Learning To Dance: Elizabeth Jolley – Her life and work edited by Caroline Lurie

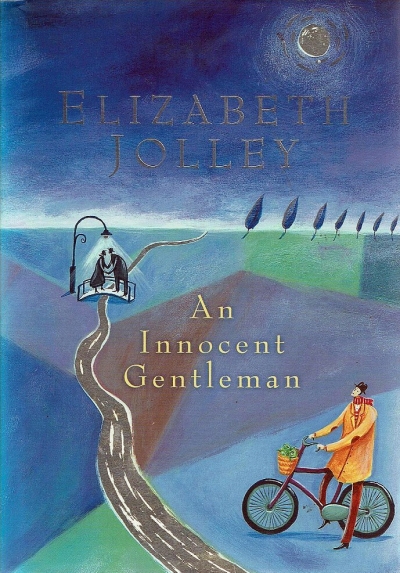

My first thought on seeing the title was that Delaware Carpenter, the loveable ‘Professor’ in An Accommodating Spouse (1999) had made a comeback. While An Accommodating Spouse had a predominantly humorous tone, this new novel is serious. On one level, An Innocent Gentleman is a Bildungsroman for a married couple in which both need to be shaken out of their arrested development. All the usual ingredients are there: a father–son and mother–daughter conflict, an avuncular friend, an epiphanous journey from the provinces to a great city, a clash of cultures, illicit sex, the discovery of a Lebenslüge against the backdrop of World War II (the result of England’s Lebenslüge) and optimistic closure as a relationship is redefined. On another level, the novel continues to explore a familiar Jolleyesque motif: the Oedipal father–daughter and daughter–mother relationships, illustrated by the Persephone and Electra conflicts, respectively. In Jolley’s novel Foxybaby (1985), Miss Peycroft advises the novelist Miss Porch: ‘and for heaven’s sake don’t lose sight of the Oedipus and Electra complexes.’ Well, Jolley never did. They are thematic concerns in Miss Peabody’s Inheritance (1983), where the middle-aged Mr Frome marries the big-breasted Gwenda who is all of sixteen; in The Sugar Mother (1988), where Leila, another voluptuous teenager, is sold by her mother to the elderly and childless professor Edwin as a surrogate mother; and, most importantly, in My Father’s Moon (1989), which constructs a most complex Oedipal scenario that has the central character, Vera, seduce her (surrogate) father and betray her mother. In this new novel, however, those two complexes exist outside the narrative and refer to Jolley’s own troubled relationship with her mother and father.

... (read more)The Australian film industry got going in the 1970s perhaps just a little before the resurgence of Australian publishing and perhaps for that reason there has been less interplay between Australian film and Australian writing than there might have been. Patrick White raged and roared about the prospect of Joseph Losey and Max Von Sydow making a film of Voss, but that was the tormenting hope of a more colonial dispensation. There have been bearable films of modern Australian classics like Stead’s For Love Alone and more or less shocking films of such nearly contemporary classics as Monkey Grip (a real monster despite Noni Hazelhurst and Alice Garner as child star doing their best) and, more recently, Lilian’s Story with Ruth Cracknell badly miscast. Cases like Fred Schepisi’s lean, pungent version of Keneally’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith are rarer than they should be though it is encouraging to hear that Mel Gibson owns the rights to My Brother Jack and intends making a film of it one of these days.

... (read more)Publishers are like invisible ink. Their imprint is in the mysterious appearance of books on shelves. This explains their obsession with crime novels.

To some authors they appear as good fairies, to others the Brothers Grimm. Publishers can be blamed for pages that fall out (Look ma, a self-exploding paperback!), for a book’s non-appearance at a country town called Ulmere. For appearing too early or too late for review. For a book being reviewed badly, and thus its non-appearance – in shops, newspapers and prized shortlistings.

As an author, it’s good therapy to blame someone and there’s nothing more cleansing than to blame a publisher. I know, because I’ve done it myself. A literary absolution feels good the whole day through.

... (read more)Would it surprise you to know that a number of our well-known writers write to please themselves? Probably not. If there’s no pleasure, or challenge, or stimulus, the outcome would probably not be worth the effort. If this effort is writing, it seems especially unlikely that someone would engage in the activity without enjoying the chance to be their own audience.

... (read more)