Opera

John Allison reviews ‘Story of the Century: Wagner and the creation of The Ring’ by Michael Downes

‘The last word on The Ring will never be written,’ writes Michael Downes in the Prologue to his new book outlining the creative history of Richard Wagner’s tetralogy. As with everything else in Story of the Century: Wagner and the creation of The Ring, Downes makes good sense, for a seemingly infinite number of interpretations of Wagner’s magnum opus are possible. Wagner believed in the power of myth, and the Ring is timeless – about more than the giants, gods, dwarves, and humans it portrays. While on one hand it seems to be a warning against the abuse and retention of power in which love ultimately triumphs, on the other it has been taken as a manifesto for German nationalism and unsavoury racial views. The Ring has also been viewed as a comment on the industrialisation of Wagner’s era, a warning against ecological disaster, as a socialist allegory, even in terms of Jungian psychology – to mention just a few examples, all of which testify to the hold it has over people.

... (read more)Michael Shmith reviews ‘Nellie Melba: The legend lives – a biography’ by Richard Davis

Product placement, admittedly not a term in vogue in Madame Melba’s time (1861-1931), was lucratively and occasionally indiscriminately deployed in her name. Since that name was itself an invention (one decided upon in late 1886, by Mrs Armstrong, née Mitchell, at the behest of her teacher, Madame Marchesi), it was officially or blatantly unofficially applied to everything from throat lozenges and mouthwash to cigarettes, motorcycles, and a sewing machine. Then, of course, there are Escoffier’s tasty tributes: Pêches Melba and Melba Toast – and let’s not forget that small town in Idaho, Melba (pop. 600). This was named not directly after Nellie, but a Melba once removed: the daughter of the man who founded the town in 1912. At the time, Melba was as fashionable a name for newborn girls in the United States as it was in Britain.

... (read more)Michael Shmith reviews ‘Carlo Felice Cillario: Italian maestro of the Australian Opera’ by Stephen Mould

My first experience of Carlo Felice Cillario was in March 1969, when he conducted the Elizabethan Trust Opera’s production of Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera at Her Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne. I had never seen the opera; nor had I heard of its conductor, whose triple-barrelled name was more indicative of a musical marking than something that belonged to an active musician. ‘Active’ was certainly the word: Cillario rushed into the pit and, afterwards, practically danced on to the stage, baton still in hand, to rapturous applause. In between, the actual performance was the first time I really connected to the compelling vivacity and innate drama of live opera. It helped immeasurably that the cast included the great Australian tenor Donald Smith as King Gustavus III. That night, all of it, still resounds in my mind.

... (read more)Picture the scene …

A space. Empty. A fall of white ash which covers all surfaces, enveloping in a fine whiteness. A party of futuristic explorers trudge through the frozen steppes. They are in the colours of artificial, twenty-first century Antarctic wear – bright red, yellows oranges. they come across a figure, buried in the whiteness, near to death, frozen. It is a girl, dressed in nineteenth-century clothes – sepias, browns, deep greens. They warm her, wrap her in insulative blankets. She begins to stammer out her story, a fantastic tale …

... (read more)'Siegfried: Another triumph from Melbourne Opera' by Michael Shmith

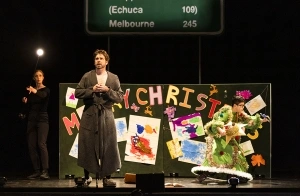

The past few weeks in Melbourne have seen a series of extraordinary musical events that collectively represent the ultimate triumph of the creative spirit over the forces of pestilence – something that applies equally to audiences as well as performers. There is certainly, hanging in the air, a palpable spirit of communion and fulfilled expectations from our re-emergence from the stygian isolation of Covid lockdown into the iridescent aura that only live performances can achieve. In Wagnerian terms, we are all Brünnhildes, reawakening from lengthy slumber to joyfully hail the sunlight. As it was – in life and in art – at Sunday’s magnificent performance of Siegfried.

... (read more)'The Human Voice and The Call: Reflecting an Australian contemporary cultural identity' by Jenna Robertson

Opera Queensland’s third mainstage production of the year, presented in partnership with Brisbane Festival and in association with Fluxus, is a double bill of two one-woman operas where a single phone call changes the course of each character’s life. First came Francis Poulenc’s The Human Voice, followed by the world première of The Call.

... (read more)A lyric future: Enabling the Sydney Opera House to fulfil its potential

The recent speech by young Swedish climate-change activist Greta Thunberg has provoked much comment and controversy. It also caused me to ponder the future of our planet and how our cultural lives will be affected by the environmental changes that will inevitably take place by the middle of the twenty-first century ...

... (read more)Géraud Corbiau’s rather schlocky biopic, Farinelli (1994) covers an important phase in the career of this most celebrated singer of the early eighteenth century. The establishment of the Opera of the Nobility in the 1730s, with Niccolò Porpora as the main composer, was a direct challenge to Handel’s ...

... (read more)Let it be said – indeed proclaimed – that Opera Australia’s new production of Wagner’s paean to life and art and love is musically as close to a triumph as it could have been. If, by the end, you feel the outside world is a better place than the one you temporarily abandoned six hours earlier, then Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg has surely wrought ...