Poetry

This new book of Vivian Smith’s is really quite a surprise. If it were the case of any other poet approaching his eighties you might think of it as rather a grab bag, knocked together out of odds and ends. It is made up of an imaginary biography of ‘Ern Malley’; another set of sonnets, ‘Diary Without Dates' ...

... (read more)Like all good titles, Kate Lilley’s Ladylike offers the reader a coded and evocative entrée into her new collection. These poems are concerned with exposing and critiquing some of the expectations of femininity, of being ladylike, as found in the past and the present, in contemporary cultures such as the cinema and in the discourses of the academy. The idea of ‘liking ladies’ is also central to these poems, as a current of desires that cuts across more conventional notions of the lady. The title also suggests a motif of mirroring, even doubling, where a self is similar to, perhaps even indistinguishable from an ‘other’, and yet is also simultaneously different, a simulacra or sign that can never be the thing in question. It is within this point of slippage – this petticoat slide between an embodiment of femininity and its repetitions or likenesses – that Lilley’s poetry operates, generating a reading experience which can be both vertiginous and full of the rigour of possibilities.

... (read more)Broadly speaking, there are two types of epitaphs: those formulated by loved ones to describe the living qualities of the interred; and those that would presume to speak from the grave. Writers, ever reluctant to pass up a blank page – even if it is a tombstone – are disproportionate constituents of the latter ...

... (read more)The Keeper of Fish by Alan Fish (edited by Philip Salom) & Keeping Carter by M.A. Carter (edited by Philip Salom)

In his Keepers trilogy, Philip Salom is an Eliotian Fisher King, exploring the fissuring of identity in a triple play of plurality. The first book, Keepers (2010), was written by Salom, but authorship of The Keeper of Fish and Keeping Carter is attributed to Alan Fish and M.A. Carter,respectively. In his role as editor for these two poets, Salom becomes their gatekeeper or, as he states, their ‘amanuensis, editor, mentor and promoter’.

... (read more)‘Dark satanic mills won the day’, S.K. Kelen tells us in one of his strongest poems, ‘Slouching’. ‘Cold modernity followed, a brooding European / monochrome hinted at worlds passing (the good old days).’ What many critics take to be William Blake’s damning of the Industrial Revolution – ‘And was Jerusalem builded here, / Among these dark Satanic Mills?’ (from ‘And did those feet in ancient time’, c.1804) – could easily have served as an epigraph for Kelen’s Island Earth. The industrial age, its intrusion upon great swathes of the ‘emerald world’, has been variously and often compellingly dissected by Kelen throughout his poetic career, which spans more than three decades and is represented in this New and Selected. Also scrutinised is industrialism’s accomplice and enabler: the increasingly global economy that, for Kelen, has made a hostile takeover of human activity at almost every level.

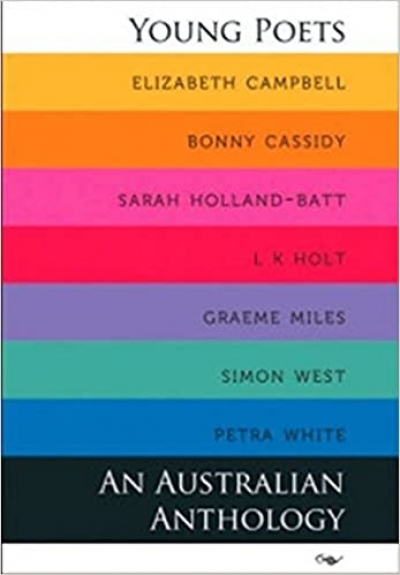

... (read more)Young Poets: An Australian anthology edited by John Leonard

John Leonard’s anthology of young Australian poets, showcasing the work of an exclusive septet, comes hot on the heels of Felicity Plunkett’s more accommodating Thirty Australian Poets (reviewed by Fiona Wright in the December 2011–January 2012 issue of ABR). Young Poets: An Australian Anthology ...

... (read more)The Keats Brothers: The life of John and George by Denise Gigante

On the morning of 17 September 1820, a consumptive John Keats and his travelling companion and nurse, the artist Joseph Severn, boarded the 127-ton brigantine Maria Crowther bound for Italy. Ahead of them lay thirty-four days of foul weather, fouler food, and close quarters shared with another consumptive (a young girl) and a horrified matron; thirty-four days, for Keats, of agonising regret and mortal fear. It was the first stage of what he called his ‘posthumous existence’: the twenty-five-year-old poet was sailing out to die. And because Keats was prevented by the well-meaning Severn from swallowing the phial of euthanasian opium he had bought before leaving England, this posthumous existence would drag on until nearly midnight on Wednesday, 21 February 1821, when Keats died in Severn’s arms in an apartment in the Piazza di Spagna in Rome.

... (read more)The Welfare of My Enemy is an unusual experiment in narrative poetry. Taking as its theme ‘the disappeared’, it is a set of narratives, a kind of anthology that imaginatively documents the myriad ways in which (and the different reasons for which) people go ‘off the radar’ and end up as missing persons ...

... (read more)Vishvarūpa, Michelle Cahill’s second collection, is a convocation of untouchables and deities – unbelieving, irreverent, and sardonic – each a proxy for an aspect of the poet’s (post-colonial) self; each a stand-in, even, for a moment in every human life.

... (read more)The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth-Century American Poetry edited by Rita Dove

‘To choose the best, among many good,’ says Dr Johnson in his ‘Life of Cowley’, ‘is one of the most hazardous attempts of criticism.’ The truth of this maxim is borne out nicely in the controversy surrounding – or perhaps emanating from – Rita Dove’s new selection of twentieth-century American poetry. That The Weekend Australian should have felt moved to comment on the situation (Frank Furedi, ‘Culture War Highlights the Banal Message of Politically Sanctioned Art’, 7–8 January 2012) is a good indicator of just how hot the issue has become. As a result, it is no longer possible simply to review the book; you have to review the controversy as well. The literary world is always set a-twitter by dust-ups between luminaries, and this one is a doozy: it features the former Poet Laureate Rita Dove, defending herself against the redoubtable literary scholar and critic Helen Vendler. Vendler attacked Dove’s anthology (and Dove herself) in the New York Review of Books of 24 November 2011, and Dove returned the favour in the 22 December issue. Thereafter, the controversy spread like algae bloom in the press and blogosphere.

... (read more)