Gender and Sexuality

Gender and War: Australians at war in the twentieth century edited by Marilyn Lake and Joy Damousi

The serious academic study of war has grown considerably in Australia in the last ten to fifteen years, bringing with it an often welcome diversification in focus and a willingness to subject old issues to fresh scrutiny. One sign of the increasing acceptance of war as a subject of serious study in the universities is the increasing number of university historians and other who, with little knowledge of or interest in the mechanics of war, nonetheless extend their work to include consideration of war and the military as these affect their particular areas of interest.

... (read more)Transitions: New Australian feminisms edited by Barbara Caine and Rosemary Pringle

In the last eighteen months three Australian feminist collections have appeared, each apparently addressed in its different way to the women’s studies market. Each title, or subtitle, is anxious to proclaim itself of the moment: Australian Women: Contemporary feminist thought (OUP); Contemporary Australian Feminism (Longman Cheshire); and now, only prevented by the limits of the print medium from flashing its red light, Transitions: New Australian feminisms from Allen & Unwin. To cultural analysts that extra ‘s’ will speak volumes.

... (read more)We are the stories we tell. We need our stories: they make us feel real. Stories give to our personal experience the particular shapes and cohesiveness we call ‘self’. When we enter into new friendships, when we fall in love, we tell our stories. The closer we draw to people, the more of our stories we are willing to risk. ‘Risk’ is always a factor. If we fall out with our closest friends, if love turns to enmity, the stories which are us may be stolen from our telling, and reshaped with malicious intent, putting at peril our cohesiveness, pressing us into despair, pushing towards the fragmentation of self we call madness. The stories which make us strong, self-confident, keep us vulnerable as well. Stories are easy to steal.

... (read more)For over twenty years Bob Connell has been a leading figure in the development of an Australian sociology, and his move from Macquarie University to the University of California several years ago was a significant loss to Australian academic life. I wish I could write Australian public life, but our press, which is fond of academics with far less to say than Bob Connell, has largely ignored his work. Nonetheless Connell’s work in class, sexuality, gender, and education is arguably the most distinguished body of social theory written in this country, and deserves far greater acknowledgment.

... (read more)Running hot on the national Austlit Discussion Group email waves recently was the question of speaking position and voice for men in contemporary critical discourse. What had occasioned the discussion was ASAL’s annual conference in Canberra, part of which had been a very successful morning at the Australian War Memorial focussing on writing and war (e.g. Alan Gould and Don Charlwood).

... (read more)Australian Gay and Lesbian Writing: An Anthology edited by Robert Dessaix

In the advertising world there’s a new and controversial trend towards catering for the X-Generation; that is, consumers with a two-second attention span, and we’re not just talking about teenagers on rollerblades.

... (read more)Pink Ink edited by Michael Hurley & Distractions by Benedict Ciantar

In Australia there is a paucity of serious lesbian critical comment regarding lesbian and gay writing. In Island last year, Dennis Altman suggested that there is little of interest being written while there is a ‘peculiar squeamishness amongst literary critics to critically comment about Patrick White or any other gay and lesbian writer’.

... (read more)Angels of Power and other Reproductive Creations edited by Susan Hawthorne & Renate Klein

In The Dialectic of Sex, published in 1970, the feminist Shulamith Firestone argued that the inequality between the sexes results from the different reproductive functions performed by women and men. In having to go through pregnancy, childbirth, and breast-feeding, women are dependent on men for support. The natural reproductive functions performed by females are not only enslaving women, they are also barbaric in themselves. ‘Pregnancy is barbaric’, Firestone argued, and women should be freed from the ‘tyranny of reproduction by every means possible’. Just as contraception had already been a liberating force for women, so would other new reproductive technologies. Firestone envisaged that ectogenesis – the growth and development of a foetus outside the womb – would be the answer for women, as long as ‘improper control’ was not exercised by men.

... (read more)The Exploding Frangipani: Lesbian writing from Australia and New Zealand edited by Cathie Dunsford and Susan Hawthorne

It is curious that in a culture where physical contact and affection is far more freely expressed among women than men that the lifestyles of lesbians are thoroughly submerged. The old bigotries are still prevalent, but it seems that the factors that have placed male homosexuality on the public agenda – gay liberation and more recently the AIDS crisis – have done little to enhance the profile of lesbians.

This silence, compounded by the apathy and stereotyping in the mass media, makes an anthology such as The Exploding Frangipani a potentially important book. But the overall assembly of the collection, and some of its more dogmatic contributions in particular, left me feeling unconvinced. I was uncertain, to begin with, at whom the book was aimed: lesbians, would-be lesbians, devotees of gay literature or, that elusive being, the ‘general reader’.

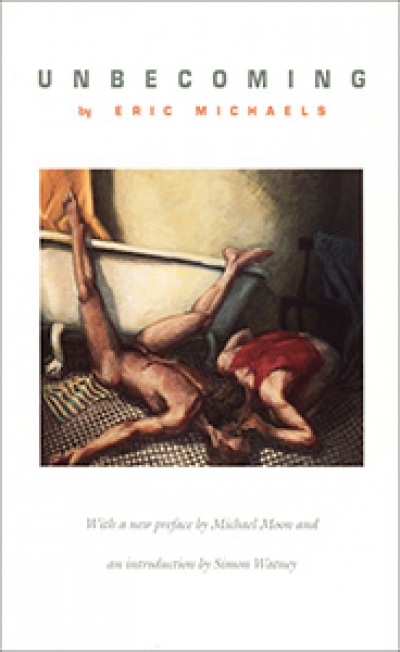

... (read more)I first came across the name of Eric Michaels through a review article he published in the journal Art & Text titled ‘Para-Ethnography’. The article rigorously critiqued Chatwin’s The Songlines and Sally Morgan’s My Place, situating them as ‘para-ethnographic’ texts. It was very impressive. The note at the end remarked that ‘Eric died on 24 August 1988 after a long period of illness’. I heard later on that he had died of AIDS.

... (read more)