Macmillan

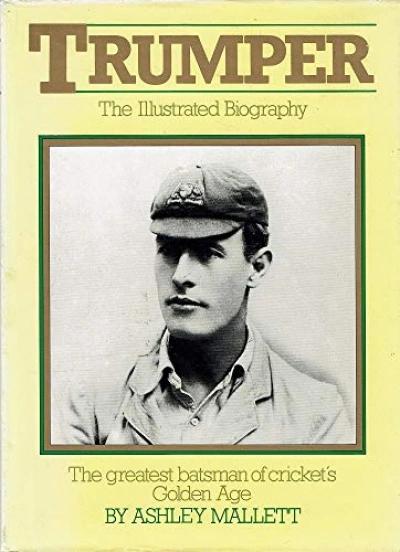

Trumper: The illustrated biography by Ashley Mallett

by Eric Lord •

The Commanders edited by D. M. Horner & War Without Glory by J. D. Balfe

by John McCarthy •

The Unnecessary War: Island Campaigns of the South-West Pacific 1944-45 by Peter Charlton

by Peter Dennis •

Solid Bluestone Foundations and Other Memories of a Melbourne Girlhood, 1908-1928 by Kathleen Fitzpatrick

by L.L. Robson •

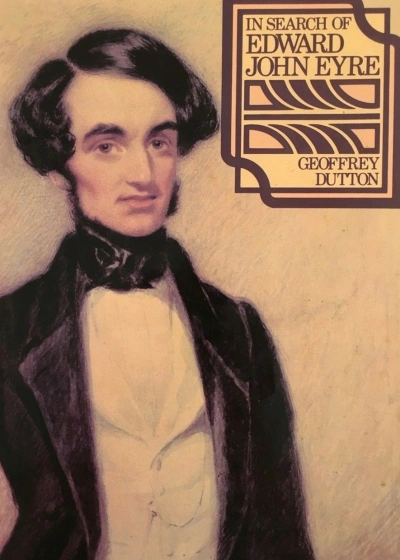

In Search of Edward John Eyre by Geoffrey Dutton

by Ray Ericksen •