Kimberly Akimbo

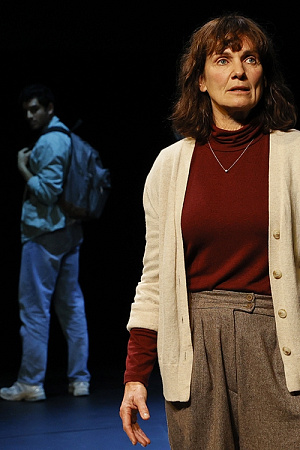

We seem, bobbing in the slipstream of mega musicals like Les Misérables and Phantom of the Opera, to be living in the era of the chamber musical. Small scale, single-set productions with high concepts and minimal staging dominate the musical theatre landscape now, from Hamilton to Hadestown. Kimberly Akimbo, composed by Jeanine Tesori with book and lyrics by David Lindsay-Abaire, follows the general shape and emotional contours of Tesori’s previous chamber musical, an adaptation of Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home. This time, Lindsay-Abaire adapts his own play about a sixteen-year-old girl who ages four-to-five times faster than everyone around her. It is intimate, charming, and emotionally resonant. If there is a sneaking suspicion that it lacks ambition, that it luxuriates in small mercies while a desperate world cries out for larger ones, it still manages to walk a precarious tonal tightrope between sentiment and cynicism. Kimberly might be akimbo, but the producers of her show are most definitely in control.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.