After the Rain

After the Rain is the fifth iteration of the National Gallery of Australia’s National Indigenous Art Triennial. Delivered by celebrated Australian artist Tony Albert, it is the first to be artist led. (Brenda L. Croft had been a practicing artist for some two decades at the time she produced the 2007 inaugural Triennial, Culture Warriors, but she did so as a curator and not as an artist). Albert resists the label of curator, preferring the title Artistic Director. This is not to diminish the work of curators, which Albert appreciates, but to elevate the role and voice of artists. As is consistent with Albert’s artistic practice, which is concerned with the (mis)representation of Aboriginal people, his curatorial approach prioritises the voice of the artist over that of the institution, marking a structural shift from representation to authorship.

Drawing on his own experience as an artist exhibiting in biennials and triennials, Albert’s personal understanding of what artists need to create their best work has informed his curatorial strategy. Albert commissioned ten multidisciplinary installations for After the Rain, providing each artist with a greater share of resources than had been possible in previous Triennials and inviting them to make their most significant work to date. However, the modest number of commissions does not equate to a small Triennial; counting collectives as well as individuals, there are over seventy artists who contributed to After the Rain, the greatest number to date.

Artist-led decision making permeates the exhibition and accompanying publication. The publication is styled after Albert’s visual journal, in which he documented the development of After the Rain. It includes Albert’s letters of invitation to each artist, and the artists’ personal reflections on what the rain means to them. Bruce Johnson McLean contributes an essay on the intergenerational legacies of First Nations artistic practice. Jilda Andrew’s evocative essay on tending to Country positions After the Rain in deep time and far into the future. Daniel Browning writes on queer Blak identity, recalling the legacy of the late Destiny Deacon, who featured in Culture Warriors, through to Dylan Mooney in After the Rain. Yessie Mosby, a member of the Torres Strait 8, speaks to climate activism from the frontlines of Zenadth Kes/Torres Strait Islands.

Visitors are welcomed to the exhibition by Aretha Brown’s expansive monochrome mural, THE BIRTH OF A NATION: THE TRUE HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA (2025), spanning the history of colonisation from the arrival of the Endeavour to the moment that Australia voted ‘No’ to an Indigenous Voice to Parliament in 2023. It is a poignant introduction to the exhibition’s conceptual focus. Brown likens the aftermath of the failed referendum to controlled burning – an event which initially feels ruinous but one which enables seeds to sprout after the rain.

The interdependence of Country and cultural survival recurs throughout After the Rain. In the language of Kamilaroi artist Warraba Weatherall, words for human anatomy are shared with that of a tree. Weatherall’s Mother-Tongue (2025) projects archival footage of deforestation onto nine mortuary tables, the conspicuously absent bodies drawing a relation between ecocide and cultural genocide. Jimmy John Thaiday’s video installation, Just beneath the surface, juxtaposing ripples on the surface of the ocean with human skin, speaks to the interconnectedness of Zenadth Kes/Torres Strait people and the sea. The artist appears entangled in ghost nets and washed up on the beach, taking the place of marine fauna, an affecting commentary on the mutually destructive impact of human-induced climate change and waste.

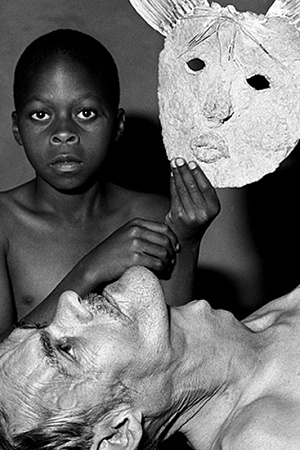

Naminapu Maymuru-White Manggalili people, Milngiyawuy Milky Way National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, 2025 © Naminapu Maymuru-White, courtesy the artist and Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre

Naminapu Maymuru-White Manggalili people, Milngiyawuy Milky Way National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, 2025 © Naminapu Maymuru-White, courtesy the artist and Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre

The cyclical nature of weather patterns coalesces beautifully with the intergenerational legacies in After the Rain. Alair Pambegan’s Minh Wuk Yot’a! (Big mob of flying foxes) (2024) draws on and extends the Wik-Mungkan ancestral story of two brothers who defy Aboriginal law. Over 600 abstracted flying foxes are suspended as though in flight, capturing the moment that the flying foxes carried the brothers into the sky, where they remain today in the Milky Way. Naminapu Maymuru-White’s Milŋiyawuy (The Milky Way) tells the star story in the Yolŋu tradition, her exquisite bark skyscapes immersing us in deep cosmic time – time, that is, since the first Ancestor and the first star appeared in the sky.

In Still I Rise, Thea Anamara Perkins reproduces photographs from her family archive on canvas. Small in scale and clustered together, the hang resembles a family photo album, capturing members of the Perkins family – well known for their public lives in activism and the arts – in personal moments of familial connection. House of Namatjira brings together works by Albert Namatjira, his descendants, and his community, and is a testament to Namatjira’s profound artistic legacy. The focal point is a stained-glass replica of Namatjira’s home at Lhara Pinta, produced to scale and by Iltja Ntjarra Art Centre with the Canberra Glassworks. For the first time, the Hermannsburg Potters have deviated from the spherical pots for which they are known to create objects that would have existed in Namatjira’s home and garden.

There is an overwhelming sense of optimism in After the Rain, a reflection of Albert’s belief that positive thinking can overcome adversity. Dylan Mooney’s empowering portraits, Resilience in Bloom, are a tender celebration of queer Blak love. Grace Kemarre Robinya captures the joy of the rain in her raincloud paintings, which are coupled with suspended soft sculptures of birds and raindrops by Yarrenyty Arltere Artists. There is a cleansing ritual at the culmination of the exhibition. Instead of a gift shop, we exit through ALWAYS remember the rain, an installation by social enterprise Blaklash, an organisation dedicated to First Nations design and entrepreneurship.

After the Rain is rich in metaphor. We see water in the soft haze of the landscape after rain, a scene reminiscent of a Namatjira watercolour; the sweat of rights hard won; the tears of climate grief and cultural loss; and in a downpour after a drought. Each installation stands up on its own and coexists as part of a greater whole, themes of intergenerational legacy, care of Country, and Blak excellence recurring continuously and cyclically, evoking the everywhen. The optimism of After the Rain does not shy away from the pain of the past – it is deeply informed by history but distinctly forward looking. These artists lead the way, sustained by the life-giving force of water.