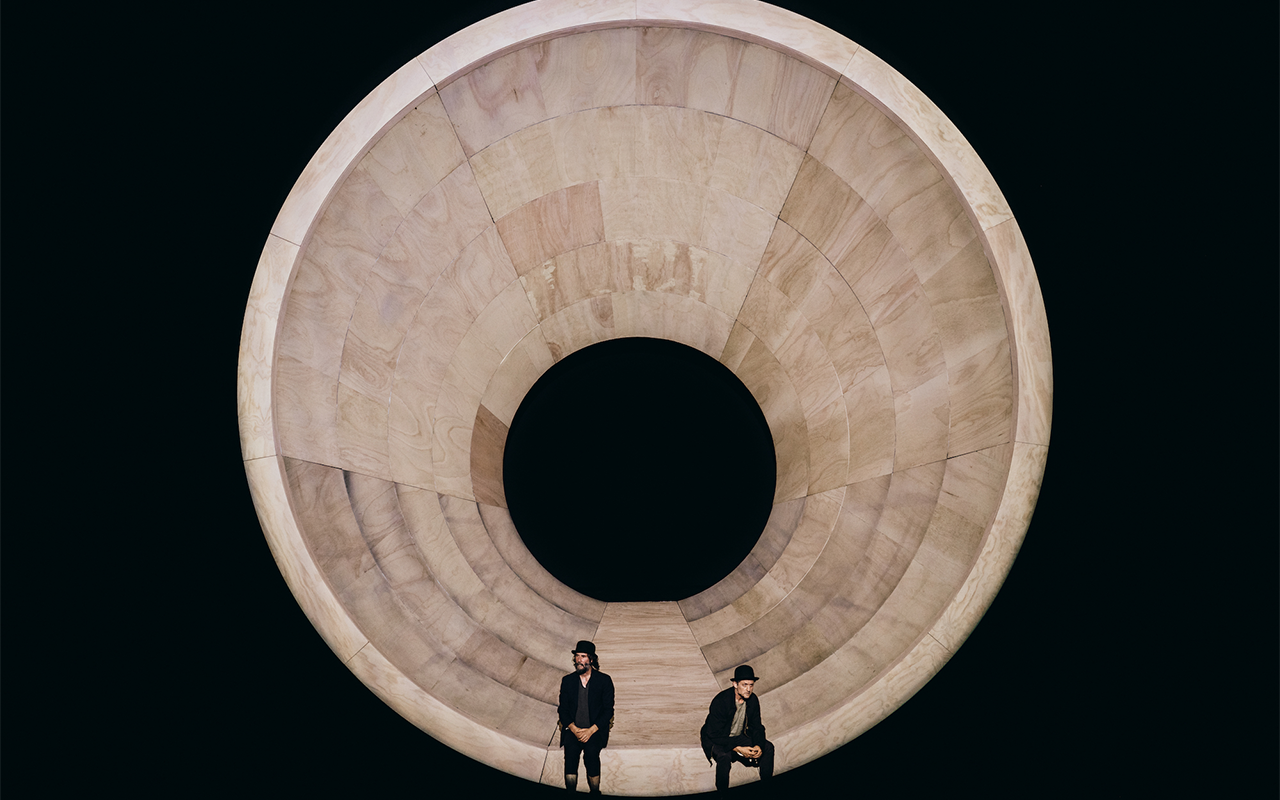

Waiting for Godot

In his Broadway debut, sexagenarian Keanu Reeves has reunited with Alex Winter – his co-star from the Bill & Ted film trilogy (1989, 1991, 2020) – for Jamie Lloyd’s bold, minimalist production of Samuel Beckett’s classic. Hollywood stars seeking to prove their mettle on the stage can wrong-foot fans, opting for experimental fare, but this tendency is strangely fitting in Waiting for Godot, a play devoid of traditional exposition, in which confusion reigns supreme.

First, electronic beats play over the PA system. Then the house lights go out before Reeves and Winter, greeted with applause, are revealed. They inhabit the third star of the show: a marblesque cylindrical structure (imagine an alternative universe in which Guggenheim architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed the iconic gun-barrel opening credits for the James Bond films) created by Soutra Gilmour, which encompasses the entire stage for the duration of the two-and-a-half-hour production. A fifteen-minute interval aside, there is no respite for two actors who draw a Generation X crowd versed in Bill & Ted, not Beckett.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.