Othello

You can make the case that Othello’s handkerchief is the most consequential prop in all of Shakespeare. Yorick’s skull and Macbeth’s floating dagger are more iconic, but neither is integral to the action of the plays in which they feature. The handkerchief, on the other hand, really is the whole of the tragedy of Othello.

And I do not mean that in a purely mechanical sense. It is a plot device, but it is also a living motif. It circulates through the hands of all the principal characters: from Othello to Desdemona to Emilia to Iago to Cassio and back again. In a drama where the dominant poetic quality, as G. Wilson Knight famously observed, is separation, the handkerchief acts as a necessary counterforce, holding the characters in their fatal circuit.

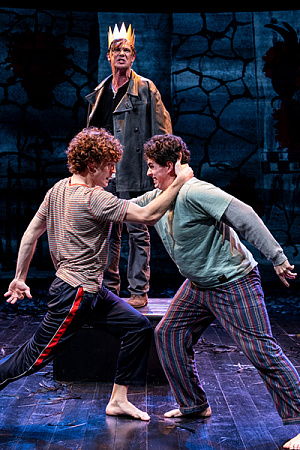

In this new Melbourne Shakespeare Company production, directed by Tanya Gerstle, the handkerchief appears much earlier than usual. The play opens with two soldiers on patrol. A woman is pursued. Cornered by one of the soldiers, she waves a white cloth as if in surrender. Then she is murdered. The other solider appears and is apparently moved by her death. He takes up the handkerchief and carries her off stage.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.