Things I Know to Be True

While there is still no release date, Nicole Kidman’s production company Blossom Films announced several years ago that they were adapting Andrew Bovell’s play Things I Know to Be True (2016) into a drama series. Given that Bovell’s play Speaking in Tongues (1996) was adapted so successfully into the film Lantana (2001), this could prove the best place for the material. The play as it stands is good – patchy, perhaps, but richly emotive and deeply considered – but it may benefit from a more episodic and visually dynamic approach. This production at Theatre Works, its Victorian première, fails to paper over its cracks; it even introduces some new ones of its own.

Bovell’s play treads some very familiar territory as it lays out its narrative of a family in crisis. There are shades of Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955) in there – the hothouse environment, the siblings scrambling to escape parental influence, the revelations around sexuality – but also his Glass Menagerie (1944), with its dream logic and slow slide to tragedy. There is a touch of Arthur Miller too, particularly the steely suppression in All My Sons (1946) and the profound disappointment of progeny in Death of a Salesman (1949). Bovell even echoes his own previous work, notably the melancholic pull of the familial in When the Rain Stops Falling (2008). This is fine, scratching so consciously at the anxiety of influence, but it does set up expectations that are hard to fulfil.

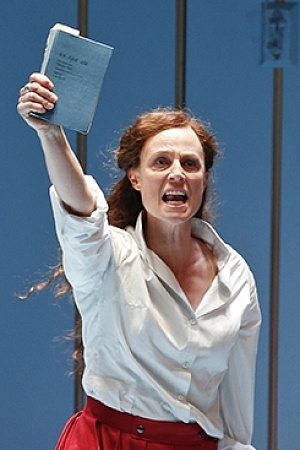

We open not with the family at the centre of the drama but with the youngest sibling, Rosie (Eva Rees), as far from home as possible. She is in Berlin, struggling to square her initial enthusiasm for travel with the strangely muted reality she finds there. A long opening monologue describes her first experience with love, followed almost immediately by heartbreak. She decides to make a list of all the things she knows for sure to be true, but she doesn’t get far: it seems she knows very little. It’s only when she returns home, straight back into the family dynamic she’d hoped to avoid, that we learn how dysfunctional it is.

Patriarch Bob Price (Ben Grant) is sweet, caring, and ineffectual, especially against the excoriating rage of his wife Fran (Belinda McClory). She has a fractious relationship with her children, especially eldest daughter Pip (Brigid Gallacher), whose marriage breakdown and subsequent relocation to Canada seem to trigger something in her mother, a shadow of another life. Eldest son Mark (Tomáš Kantor) has also recently broken up with his girlfriend, raising suspicions that he may be gay. Youngest son Ben (Joss McClelland) is his mother’s favourite, smartly dressed, upwardly mobile, if more than a little smug. As Rosie reintegrates into the ebb and flow of family life, things begin to fall apart.

Eva Rees as Rosie (photograph by James Reiser)

Eva Rees as Rosie (photograph by James Reiser)

Bovell is an exquisitely talented playwright – as When the Rain Stops Falling (2008) with its plangent mood, its expansive thematic structure and aching emotional ramifications, clearly demonstrates – but not everything in this play works as well as it might. It’s choppy and occasionally overwrought, with odd transitions and some unconvincing narrative shifts. Several revelations might work if the playwright paved a way for them; issues around trans identity, and plot points about drugs and money, feel shoehorned into the play rather than emerging organically from it. The well-worn image of family as microcosm produces some fine dramatic moments, but the whole feels less than the sum of its often startling parts.

Director Kitan Petkovski – whose work in the recent production of Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance at fortyfivedownstairs was so arresting – struggles to pull this together. Those clunky transitions between emotional states are exacerbated by a hesitant yet declamatory playing style, and Bethany J. Fellows’ set, dominated by a corralling backyard timber fence, is cumbersome and exposing. Petkovski’s blocking is strange, pushing the actors to the back or leaving them standing awkwardly off to the sides; there is often a great expanse of the central playing space completely underutilised. Perhaps this is deliberate, the exposition of a family unable to occupy its own nucleus, but the effect is clunky and unconvincing.

Performances are decidedly mixed; certain actors shine, while others fall short. McClory is a powerhouse, brittle and biting, savagely abusive but then capable of tenderness and magnanimity. Her edges are sharp, but there is a great sense of loss and sacrifice in her too. Grant is less convincing as Bob, never quite in control of the lurching emotional register the part demands. Kantor solidifies the astonishing impression he made in The Inheritance, with a performance of great skill and honesty. Rees, a rather mannered actor, occasionally rises to a kind of shabby verisimilitude. McClelland is hopelessly outclassed, bungling his key scene with a lot of ridiculous eye acting. Best of all is Gallacher, who shapes the headstrong Pip into a portrait of flinty, hard-won wisdom. She deserves a bigger part.

It is difficult not to conclude that Bovell’s flawed but ambitious play is simply beyond the skills of this production, which feels capable of a depth of feeling it can’t quite sustain. It is always tempting with this playwright’s work to lean into the sentiment – that fuzzy, insistent humanism at the centre of his work – but restraint and subtlety would have been more persuasive. I would like to see that television series, if it ever comes to fruition: each episode could focus on a different family member, their troubles and victories refracted through the prism of those two frayed and weary parents. Kidman could play Fran, and maybe Sam Neill would make a naturally taciturn dad. It mightn’t reach the heights of Bovell’s best work, but it could make a moving and lively family saga. In this format, it’s only intermittently successful.

Things I Know to Be True (Theatre Works) continues at Theatre works until 4 May 2024. Performance attended: 21 April.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.