The Tournament

Text Publishing $28 pb, 280 pp, 9780786888948

The Tournament by John Clarke

‘Paris has gone crazy.’ There are people everywhere; ‘players and officials have been arriving like migrating birds’. The German team – including Hermann Hesse, Bertolt Brecht, Walter Gropius,Thomas Mann, Martin Heidegger – have already arrived, but their officials will permit no interviews. The Americans, amongst whom are Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, Isadora Duncan, and Amelia Earhart (who flew her single seater in from New York) are raring to go. Hemingway speaks for them all: ‘Great to be here … The plane was high in the air. I slept and then I ate and drank and then I slept again. The sun came up. I drank again and then I slept. Then the plane banked and came in and landed and stopped and I could hear the great big engines being turned off. That’s the way it is.’

And that’s the way it goes. In the first few pages of this extraordinary and daring piece of work, John Clarke effortlessly maps out the ground rules simply by taking the whole thing as read. There is no anxiety to explain massive anachronisms, outlandish juxtapositions, wild propositions: these are part of the satirist’s armoury. Jonathan Swift modestly proposed that babies might be eaten in a ‘good’ cause. Clarke, with equally little fuss, puts selected canonical figures on court and lets them fight it out.

In its tone and structure, The Tournament is reminiscent of those remarkable television interviews at the end of the 7.30 Report, between John Clarke and Bryan Dawe. No matter who Clarke purports to ‘be’ in these encounters – whether John Howard, Phillip Ruddock, or other suspects – he is always unequivocally John Clarke: the same flat nasal tones, the same saturnine expression, the same balding, ducking, and weaving head. There is not the slightest attempt at impersonation. The satire is the more murderous for relying on the razor edge of words, eschewing disguises or props. Likewise, The Tournament is utterly deadpan. There are no ground-breaking manoeuvres to prepare us for the idea of it, no suggestion of deferring to our stupefaction at seeing ‘chapter’ headings such as Kafka versus D’Annunzio, Tolstoy versus Mayakovsky.

This device, a tournament that pits some of the great creative artists, thinkers, wits, polemicists, and celebrities of roughly the past hundred years against each other at the notionally sporting, but sometimes bruising, art of tennis, allows Clarke marvellous latitude for his brilliant satirical wit, his love of the one-liner, and his unerring nose for literary parody. It would be difficult and perhaps irresponsible in any review of this book not to quote ‘SuperTom’ Eliot’s explanation for his indifferent form on court:

Because I did not serve too well.

Because I did not serve.

Because I did not serve my purpose

Was not clear Meine Heimat über alles.

I think those are meine Tennisbälle.

And timing please hurry along my timing.

The return is within the serve without the frame between.

Da.

Or the description of Groucho Marx’s triumph against Heidegger: ‘By the third set Marx was running around his backhand. By the fourth set he was running around his accountant. He was trying to get his accountant to run around his backhand when the match finished.’

It is true, of course, that there is no character development and no plot beyond the progress of the tournament as it gets down to ‘the business end’. But what the hell, really.

The Tournament is all about allusiveness: Roland Barthes ‘contended … that the relationship between the commentators and the crowd is now the principal intellectual contract. In effect, he said, the player is dead’; outrageous one-liners: ‘“Who is younger,’ said the quietly confident Rushdie [preparing to play Ezra Pound]. “Who is silvier,” said Pound obliquely’; wit: Marie Stopes, whose game is ‘impregnable’, remarks that: ‘Sometimes when the balls get very hot … they can come on to you a lot faster.’ And much, much more. Not to mention the threads of historical collisions, catastrophes, and coups woven through day after day of tennis action and sometimes throwing the tournament into controversy and disarray. (Rosa Luxemburg is found dead; Karl Liebnecht is murdered; Osip Mandelstam disappears.)

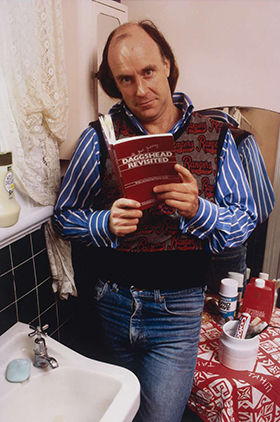

John Clarke as Fred Dagg, Melbourne, 1982 (photograph by Rennie Ellis, National Library of Australia)The form of the narrative – essentially, game following game, however bizarre the match-ups – runs the risk of an eventual flagging, a sameness, but nothing could be further from the truth. An immense, continuous, and renewing energy flows from these various dimensions of wit, allusiveness, gags and uncomfortable historical reference; not to mention the fixtures themselves, which throw up new diversions just when the joke might have lagged (in doubles: Sartre and Camus versus Magritte and Dalí, which begins with tortuous argument about whether the game should take place at all. Dalí’s contribution is, ‘My cock is a wealthy man … it has made an attractive offer for my hand in marriage’).

John Clarke as Fred Dagg, Melbourne, 1982 (photograph by Rennie Ellis, National Library of Australia)The form of the narrative – essentially, game following game, however bizarre the match-ups – runs the risk of an eventual flagging, a sameness, but nothing could be further from the truth. An immense, continuous, and renewing energy flows from these various dimensions of wit, allusiveness, gags and uncomfortable historical reference; not to mention the fixtures themselves, which throw up new diversions just when the joke might have lagged (in doubles: Sartre and Camus versus Magritte and Dalí, which begins with tortuous argument about whether the game should take place at all. Dalí’s contribution is, ‘My cock is a wealthy man … it has made an attractive offer for my hand in marriage’).

With such assorted riches, the finals tend to burst upon you suddenly. I strongly approved of the two men’s finalists and of the result, about which I’ll offer only this clue: if the match took place on a bright cold day in April as the clocks were striking thirteen on a court that smelt of boiled cabbage and old rag mats (and who’s to say it didn’t in the wild world of The Tournament?), these conditions would have suited the typically unseeded victor.

In the end, the winner is certainly not tennis. But game, set, match, and championship: J. Clarke.

Brian Matthews’s Manning Clark: A life (2008) won the National Biography Award in 2000.