The Real and Imagined History of the Elephant Man (Malthouse Theatre) ★★★

It’s a provocative idea: disability as superpower. Can we imagine Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man, as some sort mutant hero whose disfigurement is a gift? This is what the latest Malthouse production seems to be suggesting in its variation on the true story of a man with severe deformities who became a minor celebrity in Victorian England. And what does this superpower consist of? Why, simply the power to fascinate and to bewilder.

‘I am the most extraordinary thing in this massive city,’ Merrick declares to the astonishment of the hospital nurses. They are trying to keep him out of sight, to hide him in the cellar. He refuses to go gently into the darkness.

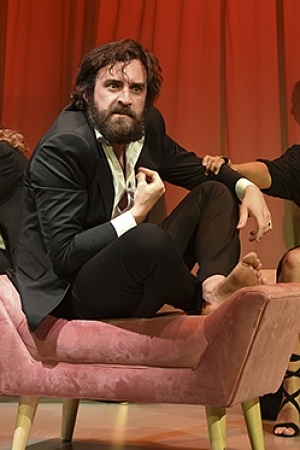

In this version, directed by Matthew Lutton with a text by Tom Wright, the Elephant Man has the power to upset any desire for order, any ingrown yearning for labels and systems and diagnostic perspectives. Like a Dionysus abroad at a time of industrial revolution, he confronts his world with the real chaos of nature, the seething energies that modern civilisation tries vainly to efface.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.