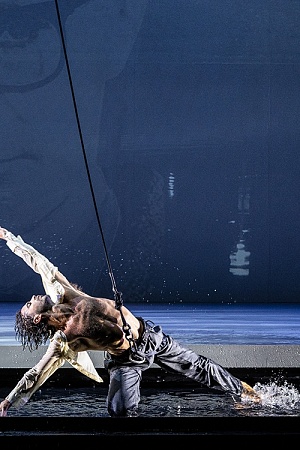

Siegfried

Opera being the most comprehensive of art forms – combining text, music, sets, costumes, acting, dance – concert versions necessarily lack clout and definitiveness. Nothing can compare with a fully rounded staged production. Certain operas, though, are peculiarly suited to the concert hall, and Richard Wagner’s Siegfried – third in his tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen – is surely one of them, with its undeniable longueurs: the interminable potion, the faintly embarrassing Tarnhelm, and our hero’s dreamlike progress to the rock on which he will liberate his sleeping aunt. Such is the beauty of Wagner’s score that one can luxuriate in it, undistracted by fussy stagecraft, so often confected (at vast expense) to hide the dearth of action and the periodic insults to one’s intelligence.

It is in Siegfried that the ponderosities of Wagner’s text (never should the word ‘libretto’ pollute a Wagner review) are most stark. Imagine how much greater (and this is saying something) Siegfried would have been had Wagner collaborated with a librettist of the refinement of Hugo von Hofmannsthal, or the singular wit and concision of Lorenzo Da Ponte. But it’s impossible to think of the master of Bayreuth ever submitting to the interventions of a mere mortal. If Verdi was lordly with his librettists, Wagner would have been positively insufferable.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comments (3)

In Tuscany, where I lived for many years, the state classical station would broadcast Bayreuth live. Growing up in Melbourne in the 1960s, my mainstay for classical music was the ABC. This was when John Charger was introducing us to Mahler and Bruckner, so difficult out of a tinny radio. I feel that the younger generation and the taxpayers are being sorely treated.

I can only echo Peter's comment - where was the ABC?

Musical events of this magnitude are not everyday occurrences in Australia Astounding that there will be no record from the public broadcaster.

Leigh Garvan