Letter from America

Politics is personal in the United States, far more private than it appears from outside. When political allegiance becomes tied to character, revealing one reveals the other. More importantly, if you critique the former, you impugn the latter. As an Australian living in Virginia, one who considers politics a form of sport, I've learned this lesson the hard way. So I had a breezy line ready for when I was asked why I'd come to see The Donald speak at a rally in Radford, Virginia: 'When the circus is in town, you want to see the elephant.' The response was predictable, but slippery: 'Well, bless your heart.'

'Bless your heart' is a delightfully polite phrase that Southerners use to cauterise impolite conversation. The problem is that they deploy it at other times too. Sometimes 'Bless your heart' is intended as a compliment; at others, a veiled insult. And it can mean anything in between: boredom, delight, frustration, amusement. It's fish-slick, dependent on context, intonation, and intimacy. It's also a fitting analogy for America – a place that is never quite as simple as it seems.

Truth is, I was less interested in seeing Trump than his audience. The Radford rally was held a month into the US presidential primary season, late in February 2016. The Trump campaign was still widely regarded as a national joke, but one that was wearing thin. If Trump was the joke, his supporters were the punchline: rednecks and idiots, xenophobic lunatics who want to 'Make America Hate Again'. It's an easy narrative to sell, and easy to buy – unless you happen to live in the middle of it.

Sometimes when Australians ask me what it's like to live here, on the western edge of Appalachia, I tell them about the time I went to see Selma (the Martin Luther King Jr biopic). The story of American civil rights played to six people; down the hall American Sniper played on six screens at once, each one of them packed. But my anecdote is a punchline too. There is complexity and rich history here on the underside of the Mason-Dixon: vibrant college towns rub up against post-manufacturing hubs, with empty-eyed factories and boarded-up main streets; there's old money, but old poverty too. There are confederate flag bumper stickers and Civil War graveyards where people still leave flowers.

Crowds gather at the Donald Trump campaign rally in Radford, Virginia in February 2016 (photograph by Beejay Silcox)

Crowds gather at the Donald Trump campaign rally in Radford, Virginia in February 2016 (photograph by Beejay Silcox)

The 'free city' of Radford is twenty-minutes from Blacksburg, where I'm in grad school. I caught a lift to the rally with a classmate, an earnest Bernie Sanders supporter who was planning to protest by pointedly ignoring Trump – sitting quietly in the audience and reading; eyes down to deny Trump the amphetamine of attention. He had been debating which book to take for days. Which title would send the right scathing message? In order to slink into the rally unnoticed, he had concealed his Feel the Bern T-shirt under a denim shirt.

The rally was slapdash, organised hastily, and late. The city felt unprepared, like someone planning a quiet family barbeque only to find the whole neighbourhood on their doorstep. The parking lots had filled by early morning; every lawn, verge, and side street was jammed with haphazardly parked cars and pick-ups. Hundreds of people made their way on foot down Radford's slopes to the banks of the New River and the basketball stadium Trump had been forced to rent because Radford University had refused to be partisan.

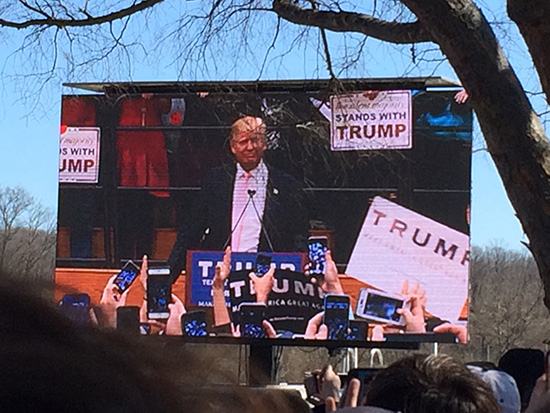

I had tickets to get inside, but a thousand people were pressing against the doors and security was overwhelmed. The auditorium seated 3,800, but word had it that more than 10,000 people were coming. A Jumbotron had been set up outside to simulcast Trump's speech, and the unticketed supporters were massing in the tentative February sunlight, expectant, staring up at the giant screen. Queuing for the spectacle indoors, I realised I was missing something more interesting outside, so I abandoned my friend and joined the festivities.

'Festivities' is almost the right word. The campaign's official rally playlist warbled through loudspeakers, incongruous in its easy-listening glory ('Uptown Girl', 'Tiny Dancer', 'Born on the Bayou'). It largely drowned out the anti-Trump protesters, who had been magnanimously allotted a cordoned space to express their First Amendment frustrations, even though – as Trump would later tell his crowd – this was a private event and he didn't have to be so nice. When protesters climbed onto the roof, they were sedately led back down by state troopers, like chastised children.

Protesters at the Donald Trump campaign rally in Radford, Virginia in February 2016 (photograph by Beejay Silcox)

Protesters at the Donald Trump campaign rally in Radford, Virginia in February 2016 (photograph by Beejay Silcox)

There were tables heavy with merchandise: Trump's trademark red baseball cap (also available in pink for the ladies, or camouflage for hunting enthusiasts), and a selection of anti-Hillary buttons referencing Benghazi and Goldman Sachs. Once Trump and Hillary clinched their nominations, these items would become more extreme – darkly misogynist in a way that sounds remarkably similar to the rhetoric launched at Julia Gillard as prime minister. But that's another story.

An Australian accent takes you a long way at a Trump rally. Once I had explained where I was from, several people offered condolences for Steve Irwin. 'I was sorry to hear about that young man of yours who passed. The one with all the reptiles.'

They asked me why I was there. I ventured my line about the elephant and returned the question. Nobody was remotely embarrassed to be there; I hadn't caught anyone out. They were polite, open, articulate. Most, though not all of them, were white. I spoke to families and college couples, to seniors and small business owners. I talked to Afghanistan vets and Iraq vets and Viet-nam vets. I met a surprisingly large number of people who were convinced that the Federal Reserve had made America 'a slave to its own currency'. I encountered undecided swing voters and a 'normal, red-blooded American man' who was unapologetically reading a 1974 copy of Playboy Magazine ('the ladies back then were more natural looking').

With the exception of some loud and beery skinhead teenagers itching for a fight, I didn't hear Trump supporters talk about Muslims or Mexicans. Instead they fretted about lost jobs and the GFC and the prohibitive price of college. I heard them talk about what they feel. 'Feel' was the most loaded word I heard all day. The language of feeling resonates where the language of thinking alienates. Thinking privileges expertise; feeling privileges the self. You can't dismantle a feeling with reason, which is why it seems to be the new watchword of American political discourse. It's arrogant to tell people they don't know their own hearts.

We're often told that Trump supporters feel angry. But anger is a symptom, not a cause. What I heard was raw and potent. I heard humiliation – humiliation undercut by fear. The American Dream was never a dream; it was an implicit promise, a compact, an equation – work hard, be rewarded. The people I spoke to had done what was asked of them and felt like fools for trusting 'the system' to deliver its side of America's grand bargain.

Trump garners allegiance because he appears to have none. I kept hearing the same line as if on a loop: 'Nobody owns Trump.' He operates outside of the 'rigged' political process; free from the 'crooked' press, from lobbyists, from the 'liberal cage' of political correctness, even from the party he purports to represent. 'Trump is his own man,' his supporters intoned. I wasn't sure if I detected envy or pride.

The mood tightened. Trump was coming. I turned to the screen, where the girls seated behind the podium (and they were all girls, glossy blondes) were reapplying their lipstick and smoothing down their Republican-red dresses. Trump had arrived, ten feet tall and so loud his brash consonants rattled in my ribcage. 'We're not going to be the stupid people anymore!' he boasted. 'We're going to be the people who bring in money. We're going to be the people that create jobs for our country; not for China, and not for Mexico.' The crowd cheered, fists raised.

Donald Trump speaks at his campaign rally in Radford, Virginia in February 2016 (photograph by Beejay Silcox)

Donald Trump speaks at his campaign rally in Radford, Virginia in February 2016 (photograph by Beejay Silcox)

Enough words have been wasted on Trump the man. What is seldom described is how catalytic he is, how he incites without personal responsibility. Trump was as reckless with the crowd as he is with truth. He is tethered to nothing, but that includes the people who think he now speaks for them – a Teflon leader who serves no one but himself, surrounded by people who feel they have nothing to lose. When you're hurting and scared, it's intoxicating to be told it's not your fault, and provocative to be given someone to blame. Minutes after I left the rally, a reporter was assaulted.

My Sanders friend had hoped for a stadium united by quiet protesters and their symbolic books, but he was outnumbered and ignored. Bless his heart. As we turned to leave, I noticed that almost everyone was wearing an orange sticker over their heart, like a neon bulls-eye: Guns Save Lives. I teach at Virginia Tech. Every day I pass a memorial to what was, back in February, America's largest mass shooting (Orlando would soon set a new benchmark). On my first day of training, I learned how to lock-down a classroom. This dissonance is exacerbating, exhausting, and wholly American.

Understanding Trump's supporters – empathising with them – is difficult, but deeply necessary. Compassion is not the same as political complicity. Trump's rhetoric is abhorrent. He terrifies me. But to be frightened of his supporters is to be frightened of my students and my neighbours, and there is already too much fear.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.