Poetry

Secrets Need Words: Indonesian Poetry, 1966-1998 edited by Harry Aveling

In Australia, despite having Indonesian as one of the languages commonly available to students in primary and secondary school, and despite having departments of Indonesian Studies in all the major universities, the literature of the world’s third most populous country and ‘our closest neighbour’ is not well known. It is mostly the province of academic specialists, not general readers. The reason for this is partly cultural in that Australian readers, particularly readers of poetry, tend to be more interested in American, European or British poetry, and partly a consequence of the poor support given to the art of translation. Yet two of the best-regarded translators of Indonesian literature, Harry Aveling and Max Lane, reside in Australia.

... (read more)What the Painter Saw in Our Faces by Peter Boyle & The June Fireworks by Adrian Caesar

These two new collections are obverses in contemporary Australian poetry and show the opposing, but often interlocked, tensions between modernism and postmodernism. The poems in both books concern themselves with art’s capacity to create or suggest other worlds. Both use painting and the visual arts in dramatically different ways as metaphors and motifs. Both collections fragment and project the perceiving self into alternative ficto-autobiographies, but with different expectations of resolution. Both conjure up real worlds of political and institutional corruption on an international scale and pit moments of fragile subjectivity and domestic harmony against grubby injustice. Both register their authors’ age at around fifty. Caesar hankers after an ethical response; Boyle juxtaposes aesthetic possibilities. Caesar’s poetry is restrained, measured, spare; Boyle’s is crowded, insistent, histrionic.

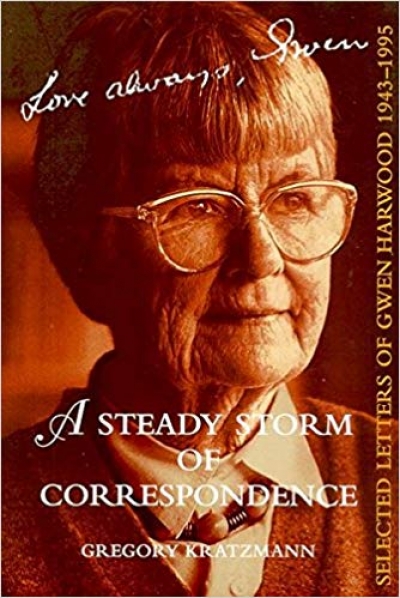

... (read more)A Steady Storm of Correspondence: Selected Letters of Gwen Harwood 1943–1995 edited by Gregory Kratzmann

and you think of

the statements you have lost,

all the things unlearnt,

the words you no longer say.

It has all been one long giving away.

(David Kirkby, ‘Water’)

The six books in Series 8 of the Five Islands Press New Poets Program come highly recommended, if only by the blurbs on their own back covers. These blurbs border on the hysterical. Cate Kennedy has ‘her heart in her eyes’, while Sheridan Linnell has written a book ‘which grows great lines like buttercups’. Michael Sharkey admires Lesley Fowler’s precision but, since he goes on to say that her poems ‘conscript experience in both hemispheres’, one assumes that precision is not his suit. Even Bruce Dawe gets carried away, assuring us that, whilst David Kirkby’s poetry may look effortless, ‘its mechanisms are merely hidden’. Hidden, that is, to all except Bruce Dawe.

... (read more)The cover illustration of Peter Porter’s selection of essays shows a mosaic from the Basilica di S. Marco, Venezia, in which Noah leans out from the wall of the Ark and releases the questing dove. The last words of the selection go ...

... (read more)Tigers and ‘the Silk Road to Istanbul’ feature in Part I of ‘1969’, the opening poem in this volume, which traces a hopeful setting forth into the undiscovered spaces of Asia and Europe. It is playfully exotic even while the homeward pull of a relationship envelops perception like a cloudscape:

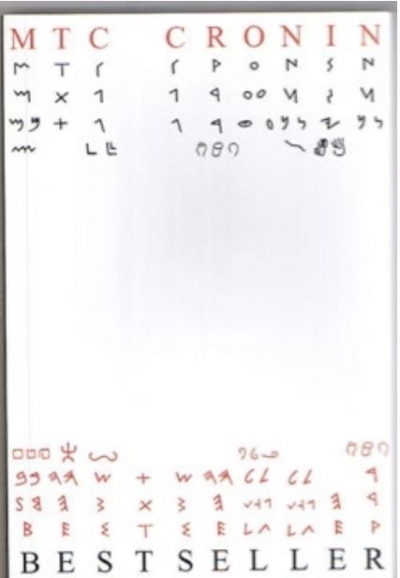

... (read more)In the August 2001 issue of Meanjin, M.T.C. Cronin writes of poetry: ‘The poems are not as useful as ribs but like them do protect life and when removed from the body grow certain murmurings of the mind.’ No matter how chaotic or runic her prose pronouncements, Cronin’s poems are quirky and original at best, diffuse and repetitive at worst.

... (read more)In the August 2001 issue of Meanjin, M.T.C. Cronin writes of poetry: ‘The poems are not as useful as ribs but like them do protect life and when removed from the body grow certain murmurings of the mind.’ No matter how chaotic or runic her prose pronouncements, Cronin’s poems are quirky and original at best, diffuse and repetitive at worst. Cronin continues to ‘just go on your nerve’, as Frank O’Hara wrote. There is the same mock candour as well as the same, often-disjointed tones as in her first book, Zoetrope (1995): ‘I do not have the time / To transform my life into a vision.’ Bestseller, Cronin’s fourth book, does signal changing preoccupations, as its title suggests. More specifically, it centres on the life of the Poet. Although Cronin’s images can lead into perky unexpected sequences, this book would have been stronger if some poems had been omitted, especially some of the shorter ones, such as ‘Cheers’, ‘Searching’ or ‘Then, Then, Then’. Some poems fizzle out in less interesting directions than those they seem to promise; they pick garrulously but semi-consciously at random images – ‘the trees wobbling like boxers / with their ungrouped leaves / moving like sand through / my outstretched eyes’.

... (read more)Chris Wallace-Crabbe’s new book, By and Large, is, despite its hundred pages, a thinner book than most of his recent volumes. The familiar features are there: a baroque and intense intellectual ambit combined with playfulness; a deep love of the sharp ‘thinginess’ of the world combined with a love of the expressiveness of the words we use to contain it; and, last but far from least, enjoyable phrasemaking. It is just that, in By and Large, the reader’s pleasure seems more attenuated.

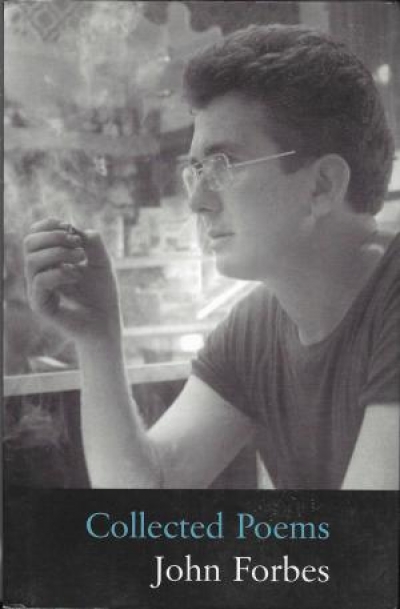

... (read more)One of the benefits of a Collected is that it places individual poems within the context of the poet’s whole oeuvre, with often dramatic consequences for their interpretation. When Leonie Kramer brought out David Campbell’s Collected Poems in 1989, more than half of the volume was made up of poems written in the last decade of the poet’s life ...

... (read more)