Australia

What the Trees See: A wander through millennia of natural history in Australia by Dave Witty

Life As We Knew It: The extraordinary story of Australia’s pandemic by Aisha Dow and Melissa Cunningham

Evolution in the Antipodes: Charles Darwin and Australia by Tom Frame

On Holidays by Richard White & The Cities Book by Lonely Planet

Babes In The Bush: The making of an Australian image by Kim Torney

What Australia Means to Me by Bob Carr & Bob Carr by Andrew West and Rachel Morris

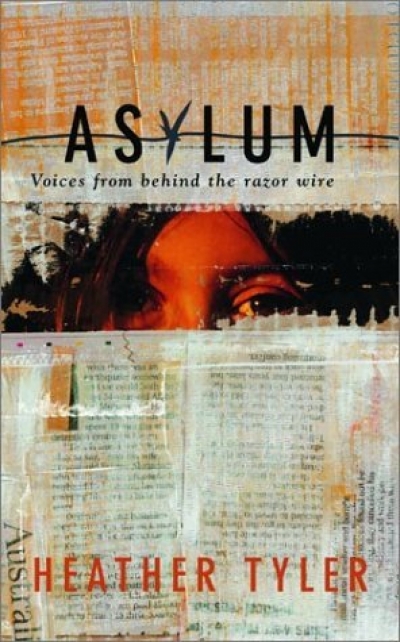

This important book succeeds in forcing us to see and hear the individuals hidden from knowledge and understanding behind the razor wire of Australia’s detention centres. The opening chapter, ‘The Iron Curtin’, presents material that, even if familiar to some, still has the power to shock. I was jolted once more by the cold facts of our treatment of refugees a ...

The arresting cover of James Jupp’s important From White Australia to Woomera features the distraught faces of the children of detained asylum seekers. As the blurb puts it: ‘There never has been a greater need for a sober, historically informed yet critical account of immigration policy in Australia.’ This is indeed a book for the times. The nation’s left/liberal intelligentsia – much-disparaged by the right as ‘the politically correct chattering élite’ – has been in a state of profound shock ever since John Howard and Philip Ruddock swept the government to victory in November 2001 on the back of their hardline policy on asylum seekers. The Tampa episode, the ‘Pacific solution’ and the rising desperation of the families incarcerated and punished at Port Hedland, Maribyrnong and Woomera are surely all too familiar to readers. Labor’s experimentation with temporary protection visas for refugees in 1990, and the introduction of mandatory detention for the ‘boat people’ in 1991, had been followed under Howard, from 1996, by the freezing of humanitarian programme levels, reductions in social security support and an increasingly draconian detention regimen. But none of these developments quite prepared observers for the Howard government’s subsequent demonising and torturing of these wretchedly desperate folk in the final stage of their attempt to find sanctuary from evil Middle Eastern régimes. And nothing, perhaps, was more shocking than the government’s dry-eyed response to the drowning of refugee women and children at sea.

... (read more)