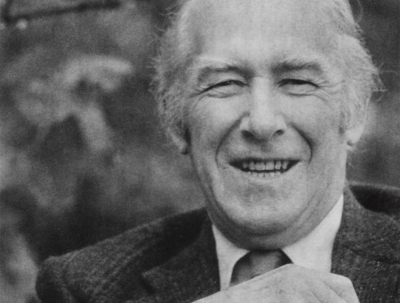

AD Hope

As physical as he was metaphysical, his playful courtesy equal to his reflectiveness, Alec Hope has mortally gone from us now. In his time, which was far from short, he was like nobody else in our literary landscape. Coming from an age in which subject matter mattered, Hope became a poet of astonishingly wide range, as of remarkable intensity. His burning star has been clouded a little in recent decades because of his investment in masculine sexuality, but he survives powerfully: sometimes hilariously. We won’t forget his Red Riding Hood devouring the wolf. Among his recent forebears, he rejoiced in Baudelaire, Yeats, and early Auden, the latter an overpowering figure when the young Australian sailed to Oxford.

T.S. Eliot’s brand of juxta-positional modernism meant little to Alec, who found it all a bit shifty, but he did share the St Louis master‘s ideas about poetic impersonality: a poem was the Ding an sich, not the shadow of its writer within it. Once, indeed, he poked mullock at Eliot by citing his putative play, Merd, or In the Cathedral.

... (read more)The Shorter Poems of Gaius Valerius Catullus by Gaius Valerius Catullus, translated by A.D. Hope

Dance of the Nomad: A study of the selected notebooks of A.D. Hope by Ann McCulloch

John Hanrahan reviews 'A.D. Hope' by Kevin Hart, 'James McAuley' by Lyn McCredden, 'Peter Porter' by Peter Steele, 'Reconnoitres' edited by Margaret Harris & Elizabeth Webby, 'Annals of Australian Literature' edited by Joy Hooton & Harry Heseltine

Oxford University Press has begun a welcome series called Australian Writers. Two further titles, Imre Salusinszky on Gerald Murnane and Ivor Indyk on David Malouf, will appear in March 1993, and eleven more books are in preparation. Though I find the first three uneven in quality, they make a very promising start to a series. In some ways they resemble Oliver and Boyd’s excellent series, Writers and Critics, even being of about the same length. However this new series is less elementary, more demanding of the reader. It is, predictably, far sparser in critical evaluation, concentrating on hermeneutics, and biographical information is as rare as a wombat waltz.

... (read more)