The Harwood Memorial Fruitcake Award

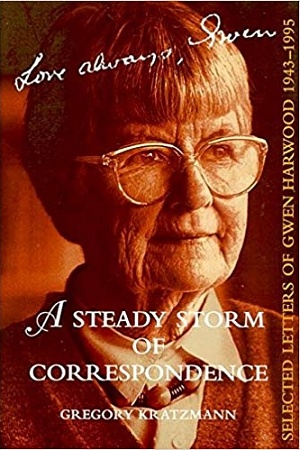

For much of her career, Gwen Harwood (1920–95) was best known for her hoaxes, pseudonyms, and literary tricks. Most notorious was the so-called Bulletin hoax in 1961, but over the years she orchestrated a number of other raids on literary targets, mainly aimed at challenging the power of poetry editors and gatekeepers. For L’Affaire Bulletin (as she sometimes called it), she submitted to that august magazine, under the pseudonym Walter Lehmann, a pair of seemingly unexceptionable sonnets on the theme of Abelard and Eloisa. Only after the poems were published did the Bulletin discover that they were acrostics; read vertically, one spelled out ‘So long Bulletin’, and the other, ‘Fuck all editors’. The first could have passed as a harmless joke, but the second threatened to bring the Vice Squad down on the Bulletin’s hapless editor, Donald Horne. He was not amused, and newspapers around the country echoed his tone of injured outrage. The appearance in print of an obscene word was shocking enough, but the revelation that the author of the sonnets was actually a woman turned shock to horror. To many in Australian society, it was an article of faith that, as an acquaintance of Harwood’s put it, ‘No WOMAN would ever write such a word.’ ‘I had a mental picture, as I heard her pronunciation of “WOMAN”, of little bluebirds with daisies in their beaks,’ Harwood wrote wryly.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.