Ian Dickson reviews 'Master Class' (Left Bauer Productions)

Cunningly promoted by her recording company, EMI, the Callas myth took off after her death on 16 September 1977 and continues to resonate to this day. Undeterred by Franco Zeffirelli’s excruciating screen homage to the diva, Callas Forever (2002), Callas projects starring Meryl Streep and Noomi Rapace have been announced.

Like most myths, this one does not really survive close scrutiny. We are asked to believe that Callas was the ultimate opera diva, uniquely great, the woman who introduced acting into the opera world – a claim that would have surprised audiences who were lucky enough to have experienced Mary Garden’s Mélisande, say, or Lotte Lehmann’s Marschallin. For someone who is supposed to be the nonpareil classical singer, her stylistic range was astonishingly limited. For a start she only sang opera. Lieder was ‘too small’ apparently for her vast talent, and she never attempted oratorio. Even in opera her range was narrow. She sang very little eighteenth-century music and, with the exception of Italian verisimo works, which could be seen as throwbacks to the nineteenth century, she sang no twentieth-century music at all. Apart from an early flirtation with German repertoire and a late one with Bizet, she sang mainly Italian composers. Possessing a biting wit but absolutely no sense of humour, she was not a great success in comic roles. So her reputation rests almost entirely on the shoulders of the tragic heroines of Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, and Puccini, with the odd Cherubini and Spontini thrown in. Within this limited field, her best recordings (such as the Berlin Lucia and the first La Gioconda) reveal a performer of great emotional depth and exemplary technique, but the overheated adulation and intemperate reverence with which she is remembered do her no favours.

However, the myth that resonates with the general public has little to do with what she actually sang. The story of the unappreciated Cinderella figure who becomes a glamorous, talented woman brought down by a combination of the men in her life and her own demons is one that audiences never tire of. Callas joins a long line from Billie Holiday and Judy Garland through Marilyn Monroe to Amy Winehouse.

Terrence McNally, who in his play The Lisbon Traviata (1989) hilariously created the ultimate Callas fanatic, understands the power of these two myths and has combined them in Master Class, which premièred in 1995, with Zoë Caldwell as Callas. At the age of forty-eight, with her own career more or less behind her, Callas gave a series of master classes at Juilliard working with twenty-five young singers she had chosen herself. These classes were recorded. Callas comes across as a firm but encouraging teacher interested in getting her students to search for the emotional truth of a role but not neglecting to work on the technical hurdles which faced them.

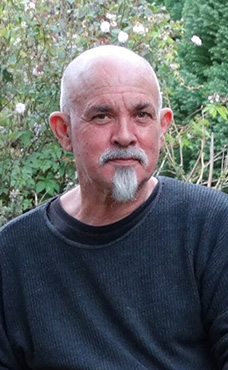

Maria Mercedes as Maria Callas in Master Class (photograph by Clare Hawley)

Maria Mercedes as Maria Callas in Master Class (photograph by Clare Hawley)

The play’s conceit is that we are the audience at one of these classes watching Callas put her students through their paces and following her as her attention wanders and she remembers key moments in her life. McNally’s Callas is the stereotypical diva demanding cushions and footstools, making demeaning comments about her rivals and continually turning the spotlight on herself at the expense of her students.

Maria Mercedes has obviously studied the recordings of the classes and completely nails Callas’s accent and the odd little grunts of ‘eh’ which punctuate her comments, but her performance is no mere impersonation.

The problems arise with the script itself. Near the beginning, when she stresses the importance of having ‘a look’ and singles out members of the audience who don’t, it seems as though we might be in for an evening of Callas as Dame Edna, which could have been interesting. But with the arrival of the first student, the wimpy, bland Sophie, the play’s interest sags, no fault of Georgia Wilkinson who has little to work with. At the act’s climax, when Callas recalls her triumph in La Sonnambula, the recording of her performance which plays in the background is so loud that Mercedes is forced to play the whole scene fortissimo and is unable to build it with the crescendo it demands.

‘The overheated adulation and intemperate reverence with which she is remembered do her no favours’

Things look up in the second act when Callas has more dynamic students to work with, and Mercedes comes into her own. She is at first attracted to the good looking, self-confident tenor (the excellent Blake Bowden), then irritated to discover that he has no real understanding of the role he is singing. When she finally allows him to sing and discovers that he is truly talented, the quiet respect with which she tells him she has nothing to teach him is truly moving.

But the play’s main confrontation occurs when Callas is faced with a soprano whose temperament matches her own. Upset by Callas’ antagonistic style, Sharon disappears only to return, determined to prove herself to this demanding monster. Callas respects her ‘mut’ and when they rehearse Lady Macbeth’s letter scene we finally understand how enthralling a master class can be. Teresa Duddy’s Sharon, in her combination of nerves, talent, and rage, gives us a performer who is as determined to carve her own path as was Callas.

This clash triggers memories in Callas of her affair with, and abandonment by, Aristotle Onassis, and Mercedes, having built up a head of emotional steam, gives us an intense emotional climax that almost redeems this meretricious play.

Throughout the proceedings Cameron Thomas, playing the accompanying pianist, gives sterling support.

Master Class, by Terrence McNally, directed by Daniel Lammin for Left Bauer Productions. Season runs from August 11–30, Hayes Theatre, Sydney; September 1–13, fortyfivedownstairs, Melbourne; September 16–19, Geelong Performing Arts Centre, Geelong; September 22–23, Whitehorse Centre, Nunawading; and September 24–25, Frankston Arts Centre, Frankston.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.