Limerence

How many times will I have to exhume you?

You rise again, a winter bulb. White corm of your face blanched as a knuckle, the quivering mycelium of your hair, stirring.

I looked first at his feet – a young man’s feet, bare and tied at the big toe for burial. There was a photograph of him in Life magazine, a full-page spread. It was August 1984 and the body of the young sailor belonging to the ill-fated Franklin expedition to find the Northwest Passage had just been discovered. His perfectly preserved, mummified remains had been exhumed from a tundra on Beechy Island in the Arctic Circle where they had lain undisturbed for 138 years. Now he was a media sensation.

Nailed to the young man’s coffin was a heart-shaped tin plaque. The hand-painted inscription read: John Torrington died January 1st, 1846, aged 20 years.

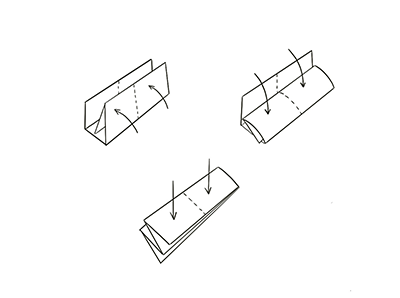

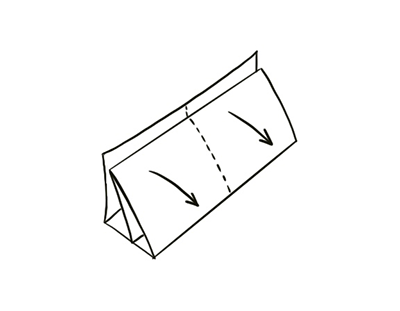

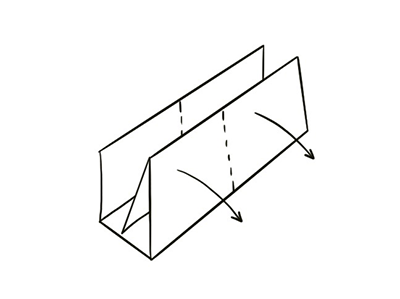

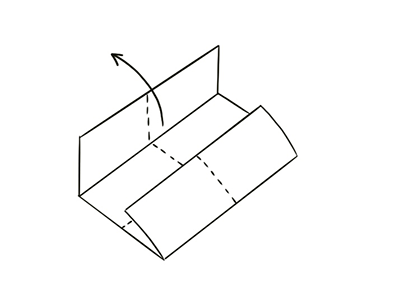

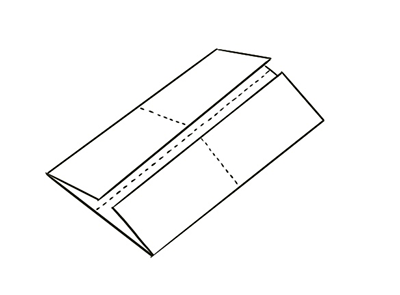

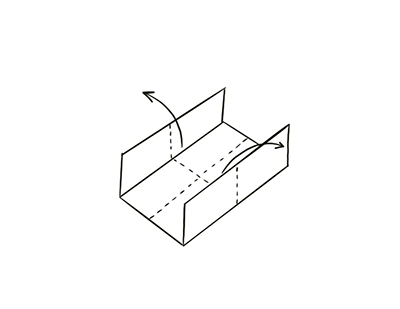

The image was astonishing – an icy cold existential slap across the face. Furtively, I cut the picture out ˋˏ✄............ˋˏ✄............ˋˏ✄............ I was compelled to keep it but could not summon the courage to look at him in his entirety. So, I folded it tightly into a wad …

… my very own origami of secrecy and postponement – and stashed it away beneath my pillow while I considered what to do next.

It was 1984 and my family lived in a small town which excelled at a crisp, suffocating kind of parochialism. Aged fourteen, I was a girl with light brown plaits and ladders in my stockings. A work in progress, my limbs were thin and mobile, my face, disproportionate. I had pointed irregular teeth and a big angular nose, Like a Roman emperor, my mother said.

I was a girl of idiosyncratic leanings, some said gifted. But giftedness can be a social liability when you are fourteen. At that tender transitional age, I was adrift in the unsettling in-between – the fraught disorienting space between childhood and youth. Between social acceptability and its opposite. I wore adolescence like a shameful, unwanted garment. Interiority was my escape.

My imaginative life was coloured by nostalgia for another century. I’d always had a leaning towards the melancholic, an ear for the saddest cadence. Reimagining the past was my preferred reverie. I pictured life in the 1840s; sepia dreams of evenings in ornate drawing rooms, huddled around an open fire – a pianola, its maudlin tunes, candlelight dancing on floral patterned walls. My adolescent dreaming was Dickensian; the ineluctable circle of domestic life, hours counted down in embroidered stitches, the heavy chiming of a clock. Filial relationships enmeshed like fine lacework – and love, love, always on the precipice of sudden and unexpected annihilation by consumption, cholera – or a drowning at sea. I felt out of step with the era, like a pressed flower, fallen from between the pages of some older book.

✄............

Our island state was an isle of ghosts. Just beyond the perimeters of town were dark stony mountain ranges. In the foothills, sheep grazed large tracts of pasture where once dense forest had stood, land laid bare by colonial occupation. Georgian style farmhouses, framed by avenues of poplar trees, dotted the rural landscape like sentinels, redolent with old fortunes and transposed notions of the pastoral idyll from another continent. In private burial plots, old tombs leant perilously in long yellow grass – their faded white picket fences worn down to the colour of dirty fleece.

We lived in a suburb dense with post-war houses and 1960s red brick veneer. Low fences and manicured lawns marked the thresholds between public and private. The family home was a white weatherboard with a concrete verandah. The letterbox in the front yard overflowed with hardware catalogues and ignored utility bills. From my bedroom window, I could see the closed down brick works, a landscape of exposed clay and gorse. I could see the town cemetery fringed by distant mountains. No doubt there were ancestors buried there. In winter, dense fog and woodsmoke settled heavily in the valley. The disused brick kilns jutted through the blanketing grey.

Nightly from my bedroom, I witnessed the real-life serial of our neighbour’s lives playing out through their lit windows. The companionable and the mundane – chaos of small children, the washing up, the tantrums – the lonely hours, the infidelities. I saw it all. When the show was over, their house gone dark, I’d close the curtains and climb into bed. The walls of my room were peppered with pencil drawings of shipwrecks, classical composers and admirals – my private gallery of the glorious dead. But now, under my pillow, was the image of a real flesh and bone emissary from the past, as urgent and true as he had been 138 years before when he was laid to rest in the permafrost. His resurrection was an indiscretion of the most intriguing kind. There was much to be done.

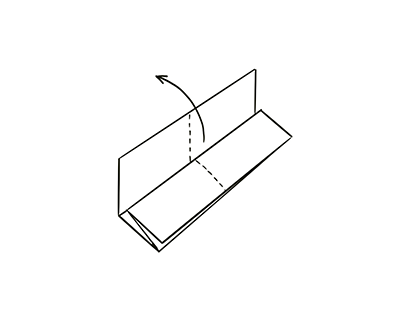

Daily I began to unfold the image just enough to reveal small portions of the body …

… the first few centimetres of the image disclosed his tender young feet edged with ice and bound together at the big toe for burial. Networks of veins embossed the dry flesh. His ankles, just visible beneath the hems of his linen trousers, were unflinchingly personal.

Quickly, I folded the image again and lodged it back in its hiding place beneath my pillow.

It was 1984 and my parents drove a Ford Falcon station wagon, with deep green duco. My mother was a reluctant housewife who wanted to be a writer, my father was a reluctant public servant who wanted to be a painter. My father wore a navy blue pullover with a neatly embroidered departmental logo on it. He always smelled of fresh stationary and sly cigarettes. There was an aura of pencil stub and carbon paper about him. Mornings, he would buff his leather shoes with black boot polish and a stiff brush over a sheet of newspaper. I loved the oily, masculine smell of the polish. He’d comb his shiny black hair neatly to one side and go to work. He was an enigma to me; in fact, I feared him. Evenings, he would return home from work, face closed and dark with exhaustion. He’d smoke a joint, drink beer and listen to the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton to unwind. The family were not allowed to interrupt him.

Meals took place around the TV, partly because mum despised housework and the dining table was buried beneath an avalanche of magazines, manuscripts, and books, but mostly because TV was sacrosanct for dad. Mealtimes were tense. Our family ate furtively, dinner plates on our laps, as dad watched his favourite programs. He was hypersensitive to noise, so I’d try to chew and swallow my food as quietly as possible, so I didn’t trigger his explosive ire. After dinner, I would retreat to my room …

Kneeling before my pillow, I’d deliberate about whether to unfold another portion of the image. Did I have the courage? I began to hold the sailor in my mind like a delicate keepsake. Each night I’d rest my head on the pillow knowing his folded image was secreted there. It frightened me – a feeling, hot and disquieting inside. Like lava and permafrost mingling in the blood. Was this love or terror? – this nauseating song of ambiguous compulsion – quietly I’d sing old sea shanties under my breath; torn between the desire to appease and the possibility I might summon him …

In these few lines which I now relate,

I’ll put you in mind of a sailor’s dream.

The town we lived in was conservative. It exerted a dour vigilance and pinched neatness that made its youth restless. In every square stood the statue of a founding father, in the central park peacocks trailed their splendid plumage across stolid turf. It was exquisite and stifling. Every day after school teens congregated at the bus mall to flirt, and smoke. They popped gum, and swapped gossip. Boys bellowed in their broken voices and jostled one another in mock headlocks showing off to the girls. The girls looked on, inscrutable adjudicators, eyelashes caked with mascara, petulant mouths heavy with lipgloss. Their hair was elaborate, flecked with synthetic blonde streaks, sculpted and spritzed into inorganic shapes with lashings of gel.

I related to none of this. My hair was plain, my clothes old fashioned and homely; we couldn’t afford to be on trend. Conspicuously out of step with my peers, I did my best to avoid these daily gatherings. Always, I tried to slink around the periphery, unseen – always they spied me, and their barrage of ridicule rose, a startling black murmuration, obliterating my light and air.

✄............

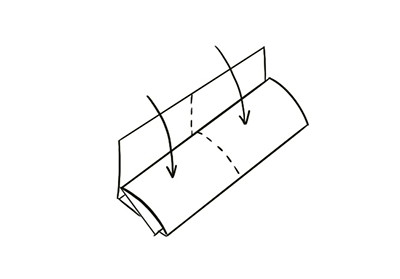

… his hands were the next part of him to come into view. A young man’s hands, long, delicate and smooth. They were bound to his thighs with strips of cotton. The strips had made bluish indentations around his knuckles – a thumbnail had detached. I could almost sense the nail on my tongue like a sacramental wafer. This was my communion. From now on, whenever I was seated, I’d make sure my hands were laid precisely the same way on my own thighs. With this little gesture I was acknowledging a private, immutable love …

At fourteen I was a girl with light brown plaits and a propensity for inconsolable rumination. Night-time was my nemesis. Haunted by the transitory nature of things, I’d compulsively indulge in anticipatory calculations: how many years of life did I have remaining? Why did time move only in one direction? How could the lives recorded by history, once so present and vivid and relevant, now all have vanished? How could the beautifully animated ones now be decommissioned dust? Why was I this person in this body?

Night after night I’d sweat in the darkness, questions swirling, my eyes fixed on the walls, the shifting procession of night shadows. Beneath my pillow, ruched at the crook of my neck, lay the folded image of the dead sailor. His spoiled beauty silently goading me. Night was a deep and glacial space – my terror, a sail that sent me scudding out on the frozen sea of my own thinking. Marooned again, I’d listen for the quiet breathing of my parents through the wall, searching for the anchor of their aliveness; the low rumble of my father’s snoring, the soft rustling of mum’s sheets as she turned over in bed, her discreet little cough. I wanted to knock urgently on their door – wanted to run into their room and shake them awake. Wake up! Wake up! We are all going to die! Inside, I was screaming, and I wanted to be rocked back to sensibility in the arms of my mother. For her warmth to be the safe mooring, her voice the unassuming force that broke the darkness open. But I didn’t and she wouldn’t, and so it was.

… retreating to that bright, white place in my mind where I carried the knowledge of him like an ache. Out, out onto the tundra I’d go, to kneel at the foot his imaginary grave. Out, out into the subtle frequencies of imagining that make time dissolve – that hint at the possibility of love reversing death. Out there I too felt like a lost explorer, looking to the horizon, some possibility of rescue – the shy hope of returning home.

I missed my mother. Episodically lost inside despair, she would become unresponsive beneath a mask of sadness. As if she’d gone in search of something and returned bruised and empty-handed. She wandered the house like a spectre. Then, unexpectedly, she would return from the wilds of her own remoteness, scintillatingly alive and engaged. I would be delirious with joy. In these moments we shared the most delicious and acute kind of friendship, a buoyancy full of playfulness and inventiveness. In this state she was attentive. She’d come into my room at bedtime with a tiny vial of perfume. It was so intimate it was almost frightening to have her undivided attention. She’d stroke my hair then daub a fragrant drop of scent on each wrist with the small glass dropper and wish me ‘sweet dreams’. The moistened glass on my inner wrists burned exquisitely, miniscule trails of love, blazed across my flesh. And then, without warning she’d be lost again. Cold and rageful, she’d withdraw to her bed.

The venetian blinds in her bedroom were always closed. In the dim, slatted light tiny fragments of sticky tape sparkled on the bedding like a strange constellation. In this mood my mother, like me, had a ritual for ameliorating her suffering. She could not bear the idea of ageing. She saw herself as a corpse-in-waiting while time conspired to destroy her – beauty, a fleeting treasure briefly granted before annihilation. Nights she’d prepare a mask of sticky tape for her face, believing that immobilising her features would arrest the ravaging effects of gravity. She’d cut little squares of sticky tape ˋˏ✄............ˋˏ✄............ˋˏ✄............ ˋˏ✄............ and line them up along the edge of the mantelpiece in the lounge room. Then she’d fix her expression in the mirror and apply the tape one piece at a time ▒ ▒ ▒ ▒ with her index finger until her face was covered by an elaborate matrix. She’d glide past me on the way to bed, her perfect, impassive face suspended under a translucent mask of cello tape.

✄............

… my gaze settled for a while on his grey linen trousers and button flies. A corner of his tucked-in, pin-striped shirt protruded through the opening of the fly – I could not bear it. It was improper, a small and poignant dishevelment, intimate and intrusive.

John Torrington, I wanted to be your comb, the mother-of-pearl buttons to fasten your shirt, your cuffs, your flies. Let me be the blanket and the shroud – the lone bright star in the last arctic night you ever saw.

I attended a state high school. It was a place of relentless torment. The classrooms smelt of adolescent musk and the terse odour of old linoleum and authority. A fine rubble of chalk and fallen dusters littered the floors beneath the blackboards. Every day felt like an endurance test, contempt, the steep face I had to climb, sharp scree of ridicule beneath my fingernails as I clung on for survival, no foot hold, no rope – no anchorman.

The students would chant insults as I entered the room. They aped my speech if I answered the teacher’s question. I was hunted in the corridors, classrooms, school grounds and the bus ride home. They’d kick the toilet door in, jeer and point at the bloodied pad in the pants around my ankles, as I scrambled to cover myself. They called me names; they punched my budding breasts. Once, they fashioned a cock out of clay in the art room, held me down and forced it into my mouth when the teacher was out of the room. It was not so much the dumb earthy phallus that offended – it was the co-operative nature of their cruelty, multiple hands pinning my wrists and ankles, fingernails dug in, eager voices baying in unison.

✄............

I hated school and most days pined to go home – but I never knew which version of my mother would be waiting when I got there. In my mind I’d rehearse what amusing story I could craft to placate her, draw her out of her depressive shell. It didn’t always work – but there was one persuasion I did have at my disposal. I could be her patient.

I began to feel sick, genuinely sick. School was a sickening. My mother had an intense fear of illness – so she’d never question my refusal to rise from bed. She granted me clemency. On these days, I would lie on the couch, draped in blankets, and feel grateful for her collusion. Illness afforded me respite from the bullying. It was also way to connect with my mother, to bypass her remoteness and preoccupation – a mutual contract; I solicited sympathy, Mum got to have companionship and control. There was something timeless about convalescence, the soft swaddling of my mother’s ministrations – the spaciousness afforded by delicacy and the special exemptions it demanded. With a hot flannel draped across my forehead and the curtains drawn against the world, it was as if we were mutually enacting our very own Victorian sickbed scene. The world momentarily pulled in, tight as a purse string. Sometimes I’d look at my own narrow white feet jutting from beneath the bedding and imagine that they were his feet.

… I began to carry the folded image wherever I went. I concentrated now on his elbows, which, like the immaculate, pale hands, were bound to his body with cotton strips. Gazing, my eye was led upwards to his torso. He wore a curious nineteenth-century shirt – it was white with thin, closely spaced blue stripes and mother-of-pearl buttons. The base of his neck, discoloured by so many years locked in ice, was visible just above the high collar. My heart quickened at the thought of what I might see next …

In the summer of 1984, I went to stay with ✄ for a holiday. I had just turned fifteen. I was excited – it was my first independent vacation.

✄ and I had always had a special rapport. He talked freely with me about large concepts (the cosmos, biology, evolution) and never condescended. He talked to me as if I were an adult. I found it enthralling – flattering. He had spoken to me this way since I was a small child. He’d once said to me You know you can tell me anything … and I did.

The landscape that summer was mesmerising; sundown by lagoons edged with tea-tree and paperbark, brackish water the colour of treacle. We talked and talked. I listened with rapt attention. He told me I was his confidant, told me I understood him in a special way. What more is there to say. You know the rest.

He said, Being a broad-minded girl you will be aware that this is not a taboo in other cultures ... I looked out the window at the darkening horizon, animals whispered and brayed in the dark, she-oaks hummed in the wind. He smelt like hay and warm marzipan. He had smelt like home – now his large hand rested on mine, heavy as a stone.

… I walked out, out, out onto that icy tundra again, to find the grave site. I lay my ear against the gravel and the blue-grey shale listening for the absence of a heartbeat.

The landscape of my dreams was a vast, frozen tundra. I was far, far away on a barren, snow swept rock, cleaning detritus from under his fingernails and buttoning his shirt against the cold arctic winds, whispering, ‘You only made it to twenty, John Torrington. You died a boy sailor with soft, uncalloused hands ...’

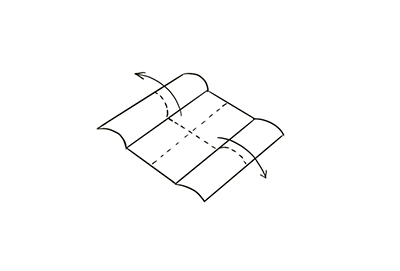

To reach Torrington’s body, the research team had to thaw the block of ice in which he lay. They heated buckets of water on camp stoves and lugged them dozens of metres to the grave where they were systematically poured over the block of ice. It was laborious, delicate work.

During thawing, the first part of Torrington to come into view was a line of mother-of-pearl buttons. Next, his perfectly preserved toes jutted through the receding ice. His face remained concealed by a fold of fabric adhered to his skin by a layer of ice. This, it was reported, created an eerie feeling amongst the researchers, as if the young sailor was somehow aware of what was happening and was resisting final exposure.

When the last curtain of ice gave way freeing the material that obscured Torrington’s face the lead scientist gasped and sprang to his feet, He’s there, he’s right there. The team stood numbed and silent. Nothing could have prepared them for the face of John Torrington …

… his face, so compellingly young, was framed by long strands of hair – a touchingly intermediate colour. The young man’s life did not seem far away. His half-closed eyes, still blue, gazed through delicate, light brown lashes. Tied around his chin and over the crown of his head was a handkerchief made of white cotton and covered in large blue polka dots.

Now his image prevented me from sleeping. He was on the backs of my eyelids when I closed my eyes – he was in all the recesses of my imagination that threw forth their pictures, uninvited. My ears hissed and fizzed, with a glacial skreich. I was sure I could hear him thawing; his internal organs shivering free of their ice bindings, the drip, drip of cellular structures partly collapsing. His waterlogged face yawning clear of its icy cradle – the precipice between the past and the present moment abolished, crumbling like snow. The vertigo of teetering closer to him than I could ever have imagined.

I dreamt. I dreamt I was crouched at the head of his coffin, my hands under his thin shoulders – I was lifting him, his head rolling onto my shoulder, his face a few centimetres from my own …

… He was very light, said anthropologist Owen Beattie, who lifted him from his coffin, and his limbs were still supple, not stiff like a dead mans. It was as if he was unconscious. As his body was freed from the ice and they lifted him, his head rolled onto Beattie’s left shoulder. The anthropologist found himself looking directly into Torrington’s half open eyes, only a few inches from his own.

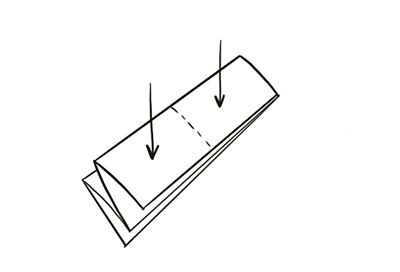

A contemporary writer described this scene as ‘a Pietà in warped time. A man cradles a boy 123 years his senior.’ I was a girl cradling the idea of a man 123 years her senior being cradled by a contemporary twenty years her senior. An origami in time. I still ask myself how the tendril of this image of disinterment – the rolling head, the gazing eyes – reached me before I had consciously read an account five years after the fact. Was it my dreaming or the anthropologist’s? Or, our collective dreaming, since his image flooded the press at the time?

Perhaps I have merely misremembered or hoped for such a dream. It doesn’t matter.

✄............

During the autopsy, the seven researchers kept Torrington’s face covered as a gesture that his privacy was maintained throughout the process. After the autopsy, Torrington was re-dressed and carefully repositioned in his coffin. Before the reburial, a note was placed beside him giving the names of the seven researchers and a description of their feelings and purpose at the site. We had some serious thoughts, says Beattie, about our feelings as human beings. It was a last private offering to John Torrington before he was once again assigned to the frozen depths. The coffin lid was then replaced and water soon began to fill the grave.

I carried his image into the following year (and five more after that). By now people were concerned by my behaviour. Upon entering class, I would lay the image open on my school desk. I’d smooth out the creases and begin speaking to him in confidential tones – it quickly cleared a swathe around me as other students moved away. He was my first line of defence – my belligerent courage, my forbidden zone, the grinning cadaver of protest. It was my way of declaring a resilience, frightening and oblique. I inhabited the space of my own alienation so ferociously it became my deliverance.

In the summer of 1985, aged fifteen years, I decided to draw him. Out of respect I did not depict his face – only those exquisite pallid young hands I had first encountered. I drew every little stone that surrounded his coffin, every swirl of woodgrain, the stripes, the shards of ice, pooled water, his hands, their bindings, his detached thumbnail, the buttons and linen, the spoilage, the improbability of him. I was taking this as far as I could go. I had faced calamity and survived. And now I was marching across the wastelands towards a new kind of beauty. A dead, lost boy, remade. A lost girl remaking; each brushstroke, pen-stroke, an act of revivification, a deepening entanglement. Like the forensic anthropologist who raised him from the ice, I was raising him again to raise myself. We were bright young things, improbable and sublime – we were defying erasure.