Letters to the Editor - January-February 2018

A vexed issue

Dear Editor,

Your editorial on the issue of marriage equality in the December 2017 edition of ABR was a superb contribution. It reminded me of the worthiness of the expression of measured, deliberate, and forcibly expressed anger when it is appropriate.

I disagree, though, with your linkage of same-sex marriage and euthanasia, citing majority support for both. Marriage equality got the nod because it was just, not simply because it had majority support. Arguably, capital punishment for major crimes would enjoy majority support here too. Euthanasia is a vexed and misunderstood issue that prevails in the public mind on the basis of multiple misconceptions about the realities of its implementation and alleged need. There are still few countries in the world where it can be easily accessed. That alone raises alarm bells. What are the odds that Australia, notoriously backward on so many points, should suddenly be at the forefront of progressive thinking on this particular issue?

Pat Hockey (Facebook comment)

Svetlana Alexievich

Dear Editor,

Dear Editor,

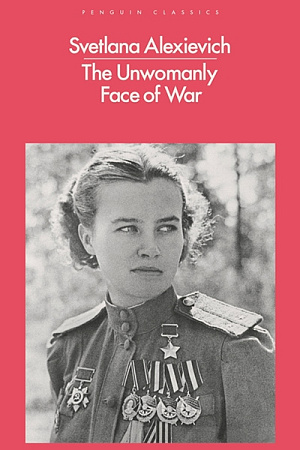

Having been reduced to skim-reading to get through the 470 pages of transcribed recorded interviews that make up Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time, I was eager to read Miriam Cosic’s review of The Unwomanly Face of War (ABR, November 2017) to get a professional critic’s explanation for the Nobel Prize in Literature, to which, as she reports, ‘the response in the Anglophone world was general bewilderment’. Instead, Cosic refers to the familiar shortcomings – ‘barely edited’... ‘without imposing narrative or explanation. Even biographical information is scant’... Cosic does suggest there might be an explanation for awarding the Nobel to a ‘kind of a journalist, kind of a social historian’ – the first in non-fiction, she might have pointed out, since Winston Churchill in 1953: ‘The response in Russia was the opposite: intense, personal, targeted. Alexievich wasn’t a real writer, detractors said; she had only won the Nobel because the West loves critics of Putin.’ If she wasn’t so hostile to Putin’s Russia, Cosic would have followed this up. Alexievich has no popular following in Russia. By contrast, previous Russian winners of the Nobel – Bunin, Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn, Sholokhov – are still household names. Alexievich is regarded as an ethnic Ukrainian with Belarusian citizenship writing in the Russian language, her output consisting mainly of poorly disguised political polemics.

L.J. Louis (online comment)

Comment (1)

Dear Pat Hockey,

.

In Peter Rose’s editorial of the December edition on marriage equality, he wrote :

« The New South Wales and Victorian state parliaments are close to legalising euthanasia (a right supported by an even more overwhelming majority of Australians, as revealed in countless opinion polls) »

To which you objected :

« Marriage equality got the nod because it was just, not simply because it had majority support … »

It is difficult to imagine a more fundamental human right than the right to life. But we have to recognise that life and death are two sides of the same coin. There can be no life without death and no death without life. The two are absolutely inseparable. If life is a fundamental human right, then death is too.

Life is a self-sustaining process that began a long time ago. Birth is not the beginning of life and death is not its end. Birth and death are simply part and parcel of the process of life which is relayed by the individual members of each species, in exclusivity, to the next generation of the same species. It is this whole process, not just one element of it, that is a fundamental human right accorded by nature.

As such, it is not a question of it being "just" or "unjust". It is a natural, inalienable right that has nothing to do with morality. There is no morality in nature, just what is most efficient for its evolution and perpetuation.

It follows that if the good life we want is freedom to do as we please, limited only by the freedom of all others and whatever other restrictions we voluntarily consent to in the common interest, then that should be made law through the democratic process, as should the fundamental, and inalienable right to life. The same goes for death. If the “good death” we want is a peaceful and painless death, preferably in a warm, cosy environment, then that too should be made law and apply throughout the nation, as should the fundamental and inalienable right to death.

Euthanasia is not an ideology designed to supplant archaic religious dogma or obsolete, 4th century BC, Hippocratic oath. It is simply the provision, by a mature, democratic society, of access to a “good death”, in the best possible conditions of comfort and security.

Nor is it something for religion or the medical profession to decide. The role of religion is to provide spiritual solace to those who require it and that of the medical profession to provide the most effective medical assistance possible. Euthanasia, or “good death” (from the Greek eu, "good" and thanatos, "death"), has to be the personal decision of the individual exercising his free will without, or in spite of, any outside influence.

It is the role of democracy to make this possible and that of justice to ensure that it is put into practice with full respect of the highest standards of integrity, diligence and professionalism.

.