Lyn McCredden

The Fiction of Tim Winton: Earthed and sacred by Lyn McCredden

by Tony Hughes-d'Aeth •

Tim Winton: Critical Essays edited by Lyn McCredden and Nathanael O’Reilly

by Delys Bird •

Motherlode: Australian Women’s Poetry 1986 – 2008 by Jennifer Harrison and Kate Waterhouse

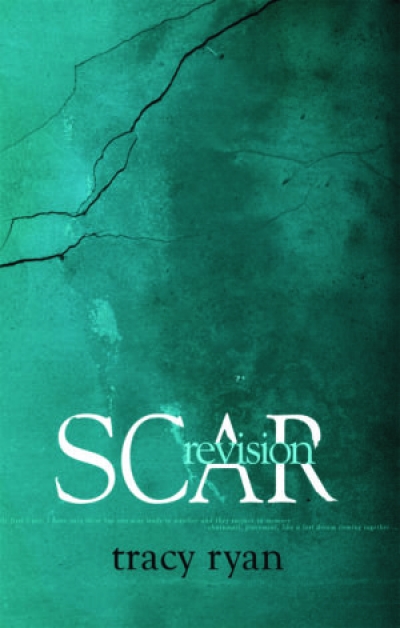

by Lyn McCredden •

Meanjin, Vol. 66, No. 4 & Vol. 67, No. 1 edited by Ian Britain & Griffith Review 20 edited by Julianne Schultz

by Lyn McCredden •

Meanjin vol. 66, no. 2 edited by Ian Britain & Griffith Review 17 edited by Julianne Schultz

by Lyn McCredden •

Westerly edited by Delys Bird and Dennis Haskell & HEAT edited by Ivor Indyk

by Lyn McCredden •